My beautiful wife Mary had just come back from taking our son Henry to the playground. He’s 3 years old now and, although he can’t exactly play with them, he likes watching the other children on the swings and slides. We try to socialize him as much as possible, carrying him over to other boys and girls so he can smile at them, touch them and be touched by them.

“How’d it go?” I asked her. Henry isn’t always very energetic. Sometimes, on good days, he’s upbeat and laughs easily and often. When he’s like that, he has a wonderful time at the playground, sitting in Mary’s lap or carried in her arms, watching and giggling. Other times, he gets grumpy, or worse still, he stares off into space.

I could tell right away that today hadn’t been a great day.

“Henry was OK, a little grumpy. It was OK,” she said, drawing out the word — O-kay.

“Did you break down?”

She started crying, words pouring out.

“It wasn’t Henry. I wasn’t even seeing the other kids. It’s the mothers. There were two mothers and one was telling the other woman how ‘impressed’ she was with her daughter’s development. She said she’d noticed how the girl was progressing so quickly. I mean, ‘impressed’? Why impressed? Henry isn’t doing what those kids are doing, so is that less impressive?” she hung on the word. “And why impressive? What did that mother do that I’m not doing? Just because her daughter is walking, why is that ‘impressive’ for her?”

“I understand,” I said, and I do. Mary knows it’s perfectly normal for parents to exchange small compliments about their children. She just needed to vent.

“I know it’s good for Henry to go to the playground. He likes seeing the other children. He needs to socialize, but the parents. I’m sitting there, dreading someone will come up to me. I’m trying not to make eye contact, hoping they won’t ask me how old he is. What am I going to say, ‘yes, he’s 3 and, no, he doesn’t walk or talk?’ They’re not going to want to have a play date with Henry.” Mary was crying in a steady stream.

“I know,” I said. There isn’t much more to say.

Mary is stronger than I am at dealing with these kinds of encounters. She takes Henry to music classes, nursery rhyme groups and soft-play classes nearly every day. While I also sometimes go, I find it a kind of self-inflicted torture, sitting on some mat in the corner of a room, holding Henry as other parents and their children romp around, singing, dancing, clapping and shaking maracas. But as hard as it is for us, it is infinitely harder for Henry.

He was diagnosed with a severe genetic neurological disorder just over one year ago. Some days, it feels like we found out yesterday. Most of the time, it feels like a lifetime ago when we didn’t know he had this disability. The disorder known as Rett syndrome is far more common in girls. In boys, the mutation is often fatal.

Henry is generally alert, smiles and recognizes us, but he can’t sit up straight for very long, let alone walk. He needs us to feed, bathe and do just about everything for him. There is currently no cure for Rett. Doctors say he’ll likely need what’s called “total care” for the rest of his life.

While we have resigned ourselves to the new reality, taking care of Henry is increasingly difficult because of basic physics: He’s getting heavier. For most parents, a growing child means the start of a new stage of life with friends, sports and school. For us and other parents of children with cognitive and mobility issues, growing up means approaching a terrifying tipping point when our children become too heavy to lift and move safely.

It’s not just that Mary and I need to carry Henry up and down stairs, or lift him off his bed, or take him out of the bathtub; we have to move him constantly. Since Henry can’t entertain himself like other children, we have to make small adjustments to him all day, sometimes picking him up and moving him just a few feet so he can play with a toy out of his reach. If left alone, Henry has a tendency to stay put and play with the same toy, pushing the same button repeatedly. Mary is always next to Henry, always moving him, always trying to keep him engaged, entertained, alert and happy. She sings him 100 songs a day. She reads him 10 books by lunch. She sits on the ground and plays with him whenever he is awake. She moves his toys away from him — even just a few inches — so he will exercise by belly-crawling to them. People ask me how Mary is doing. I usually say she’s busy. She’s also exhausted. She is Henry’s everything partner, but that was easier when he weighed 20 pounds. It’s harder at 30 pounds. It will be extremely difficult at 75 pounds and more. I worry Mary or I will drop him on the stairs, or when he’s wet and slippery after a bath.

To delay the use of hoists or other apparatus, Mary is working out like mad. Naturally slim — she has one of those metabolisms— she’s trying to get stronger. We’ve bought dumbbells. She does curls and squats. She walks up and down our neighborhood wearing a 30-pound weighted vest. For me, there is no greater expression of a mother’s love than watching Mary walk up a hill in her heavy black vest so that she can carry Henry for another few months, a year or even two, pushing back what may be the inevitable, putting Henry in a wheelchair.

But Henry is making amazing progress. He’s getting stronger. He’s sitting up straighter. He can focus for longer. He doesn’t talk, but he verbalizes more. In addition to regular physical therapy sessions, we put Henry for an hour every day in a “standing frame,” a device that holds him upright. We’re not giving up by a long shot. We’re determined he will walk one day. But working out the complexities of Henry’s mind is an even greater challenge than training his body.

His mind works in ways that we, and doctors, don’t fully understand. I worry he increasingly feels locked in. He’s getting more curious and more aware; but as he’s unable to express himself, he increasingly gets angry. He screams and sometimes tears will run down his face and we don’t know why. I carry him with my arms cradled under his bottom and with his face pointing toward my chest. He recently bit me and drew blood. Sometimes he’ll claw at my, and Mary’s, face and neck. We are diligent about keeping his nails short. I don’t want him to surprise us and we end up dropping him. We are trying to teach Henry to communicate so he can feel less frustrated. We have a special iPad linked to an eye-gaze sensor. The sensor tracks his eye movement. The idea is that he can look at something on the iPad and we will know what he’s looking at and therefore better understand what interests him. Some non-verbal children and adults use this system to communicate complex thoughts. So far we have not had success, but it takes a long time and involves a lot of trial and error. So we push on.

As I write now I realize I exaggerated when I said we are resigned to the new reality. It is still very much a work in progress. The psychological strains work away at you like drops of water, burrowing into the hardest of stones. I broadcast for a living and have a son who cannot speak. I write books and have a son who cannot read. While reporting in war zones, I wrote a series of poems for my future child, who cannot understand them. Is it irony or math or God who conspires to find the very places where we are most sensitive and push on them? Mary and I are becoming stronger, physically and mentally, because of Henry, but I must say I wish we didn’t have to.

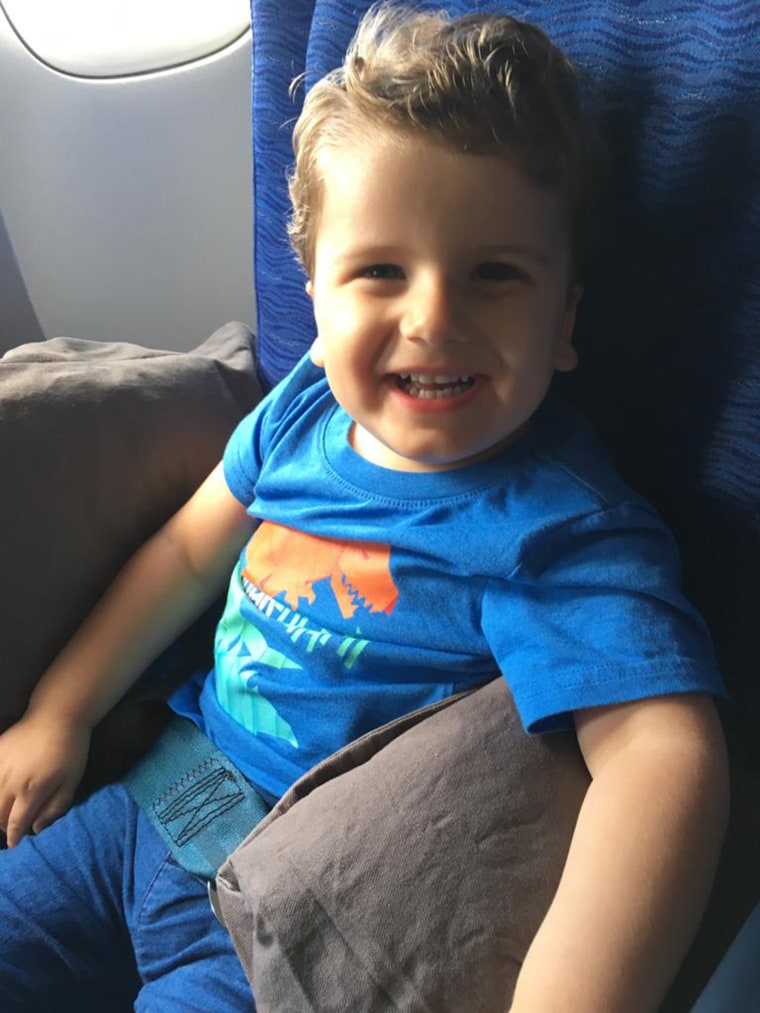

None of this means we don’t enjoy our time with Henry. I can’t imagine a child who is showered with more love. We gather on our bed several times a day for what we call “cuddle parties,” where we kiss him, rub him, praise him (he loves to hear his name and be praised) and curl his thick, gorgeous hair in our fingers.

People often ask me — and I appreciate it — how Henry is doing. I don’t have a quick answer, but there is hope in this story. There is even a chance Henry’s story could have a fairytale, after-school-special ending. Henry’s disability is profound, but is also profoundly unique, and anything that rare is valuable. Doctors think Henry’s exact genetic mutation is one of a kind. They think — and I’m still blown away by this — that he could hold the secret to finding a cure not only for himself, but for many other children with special needs.

We are fortunate to have linked up with Dr. Huda Zoghbi, an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and director of the Duncan Neurological Research Institute at the Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. She and her team are really doing mind-blowing work. Dr. Zoghbi discovered the genetic cause of Rett syndrome several years ago and her lab is now experimenting on Henry’s cells. They’ve already created genetically modified mice — “Henry mice” — that are biologically programed to have Henry’s exact mutation. Dr. Zoghbi believes if she can find a way to fix Henry — who is extraordinarily healthy given his condition — it could open the door to treatments for Rett syndrome, and potentially thousands of other genetic disorders, impacting millions of children around the world.

If the little Henry mice reveal their secrets, this story could have a truly amazing ending. I can already see the storyboard. (Spielberg, take note.) A war correspondent travels from conflict to conflict, documenting misery and suffering. After being kidnapped he decides to get married to his longtime love and start a family. They have a beautiful boy, only to discover he has profound disabilities. They hit rock bottom, but through their love, this amazing, one-of-a-kind child allows a team of dedicated scientists to find a cure for him and millions of other children. Henry fixes himself and spreads happiness. I wish for this more than anything in the world. Maybe it is a fantasy, but Dr. Zoghbi thinks it’s not only possible, she’s cautiously optimistic it will work. So maybe this story — Henry’s story, our story — becomes the greatest news story I’ve ever told.

To find out more or support the research being done with Henry, go to DuncanNRI.org.