On Mother’s Day, I sometimes drive a familiar route by memory. I drive past where my son was born, past the house in Seattle where we lived in when he was a baby. I drive to the docks where we watched ferries slide across Puget Sound when he was little. “Car boat,” my son, who was deaf, would sign, pointing excitedly when one came into view.

I drive to the high bluffs where we went to spot whales migrating past the shore, and I imagine them gliding by, hidden below the surface. I think of Tahlequah, the orca mother whose grief captured the world’s attention, pushing her dead baby through the water for 17 days before finally letting her go.

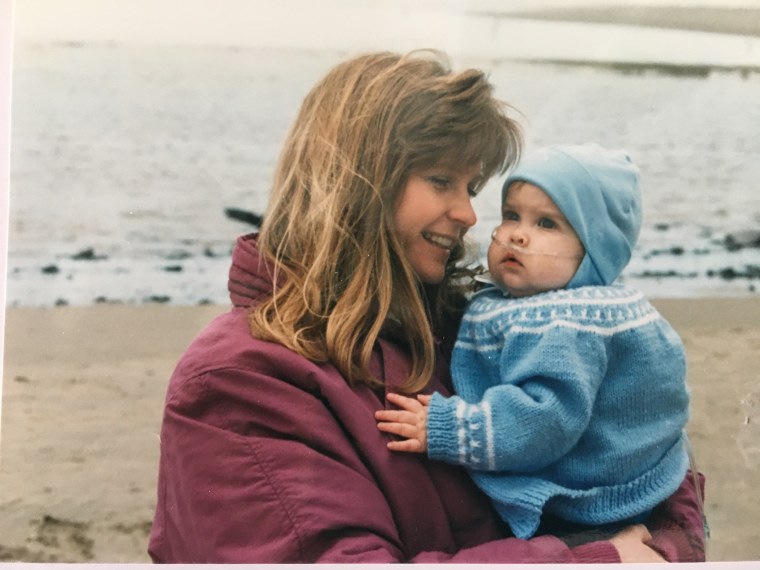

I am a ghost mother. My only child, Christopher, died unexpectedly when he was 7. Though it has been many years, I still carry my grief with me the way Tahlequah carried her baby. The whale made briefly visible the world I live in every day, then she disappeared again into the deep.

There is no English word for a parent whose child has died, no equivalent of ‘widow’ or ‘orphan.’

There are few people more invisible on Mother’s Day than the mother who has lost her only child. Every time the holiday rolls around with its glitter cards and cheerful bouquets and celebratory waffle brunches, I go into mourning, not only for my son, but for my role as a mother. There is no English word for a parent whose child has died, no equivalent of “widow” or “orphan.” It’s as though we don’t exist.

There’s a reason for this. A child dying is often cited as a parent’s greatest fear. The deaths of children are seldom spoken of. No one wants to admit that children die, perhaps for fear that it will happen to them or invite some curse on their own household. So many times, people have told me, “I don’t even want to imagine ...” as their voices trail off.

Related essay: Closure is a myth: Getting through Mother’s Day without my child or my mom

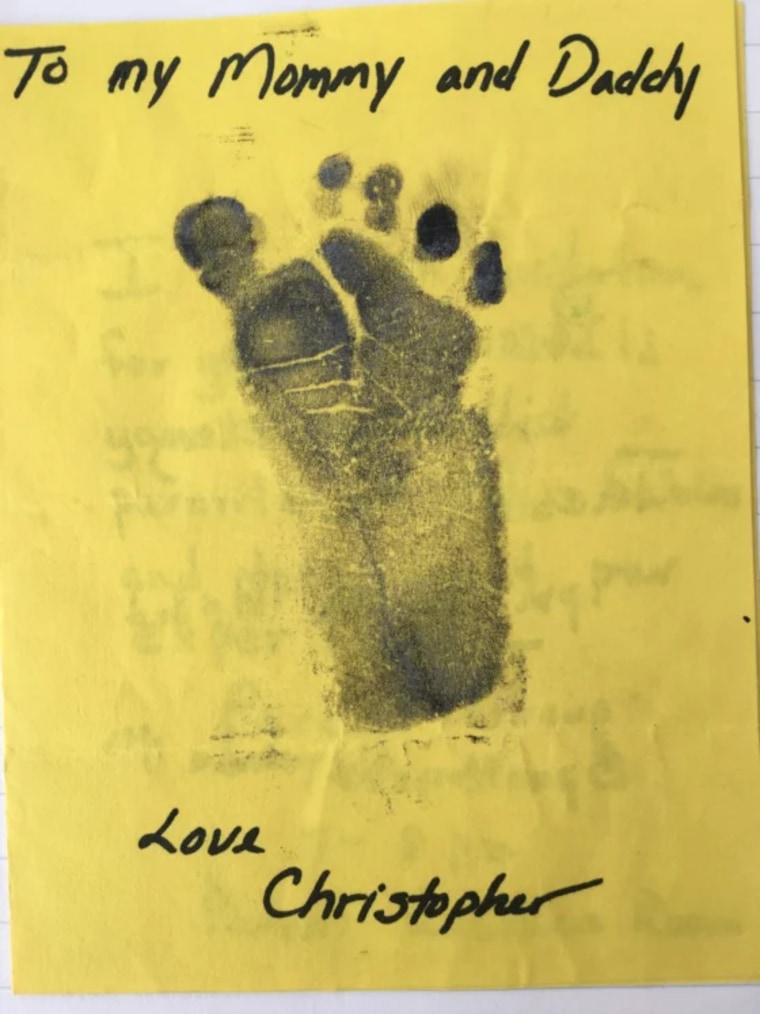

The silence goes both ways. In the early days after Christopher’s death, I stopped saying yes when people asked if I had children. I didn’t join in other parents’ conversations about their kids; my presence made people self-conscious. I stopped saying his name out loud, hoping to avoid questions, because people shrank away from me once they realized he was gone. But this is the thing: He isn’t gone. The child who made me a mother hasn’t disappeared for me. I am still a mother, and I still celebrate being his mom.

Mothering is a long process of letting go

Christopher was born with failing lungs and kidneys, the result of a congenital birth defect. By all accounts, he was not supposed to live longer than Tahlequah’s calf, who died a half hour after she was born.

But Christopher did live, and by the time he came home for the first time five months later, his father and I knew this much about him: He was a stubborn, happy child who could make friends with anyone, even if they came wielding needles to do his daily blood draws. He lived a life of fierceness and joy. Though he was profoundly deaf, he was not silent. He filled our lives with laughter and exuberant sound. We learned language together. We bumbled through our early attempts at signing, until we could understand each other. “Same,” he signed on the day he graduated from kindergarten, pointing at me then at himself.

People say the moment you become a mother is when you give birth or first hold the child who will be yours in your arms. I say it is this one: the moment we first learn mothering will be a long process of letting go.

I still sometimes reach for his hand when I cross a street.

My own reckoning with this came early and abruptly. Christopher was still an infant in intensive care at Seattle Children’s Hospital. One evening, coming back from the hospital cafeteria, I heard an alarm over the loudspeakers about a code in the neonatal ICU. I rushed toward the unit. Through the window, I could see a phalanx of yellow gowns huddled over Christopher’s Isolette. When I started to go in, a nurse stopped me at the door. Frantic, I pleaded with her to let me do something, anything. I still clung to the illusion that being his mother conferred some magic power that would keep him safe from harm. But all I could do was haunt the waiting rooms and hope. His life was his own, and he would lead it separate from mine, a wrenching separation, but an inevitable one.

My letting go continued after his death. For many years, I bought toys for him, ones that matched the ages he would have turned. Christopher had loved to sprinkle my garden with his yellow plastic watering can until he, too, was soaked, and on the bottom shelf of my potting bench, I kept a set of children’s gardening tools I’d bought him for his eighth birthday, the first birthday that never came. The year he would have turned 10, I bought a Rubik’s Cube. I still sometimes reach for his hand when I cross a street.

How grief becomes easier to carry

A whale carrying her dead young is not unusual, though Tahlequah carried hers for an unusually long time.

It has been more than 25 years since my son’s death. But my grief is no less heavy for having carried it longer. It’s just that I have found a way to distribute its load, placing it just so on my body until it is a part of me and does not weigh me down. It’s this way for many of us who have lost children. The heaviness builds strength, like lifting weights, until we can shoulder more without collapsing.

Related essay: Grieving mom shares how she gets through the holidays

But there are things that make it easier to bear, especially on Mother’s Day. I don’t need waffles or bouquets, but I do need to be a mom. It helps when you ask me about my son and use his name. It helps when you let me brag for a moment about how bubbles made him laugh, or how proud he was the first time he hit the ball off a tee. It helps when you remind me that I was a mother and when you talk about all the ways those of us without children, by choice or circumstance, still put mother energy into our lives and work. Don’t be alarmed if your questions bring on tears. Those are tears of gratitude.

I go sometimes to a support group for mothers who have lost children. I don’t always remember all the names of the other women in the group, but I do remember their children’s names, because I hear them so often in the stories that pour out. The group is where I can be Christopher’s mother again, say his name and not fear people will flee. The former nurse who runs the group refers to us collectively as “the moms.” We are a large and largely unacknowledged tribe — those of us who have lost children — and we carry our young forever.

In the midst of the pandemic, news circulated that Tahlequah was pregnant again. Photos of the whale’s baby bump sent a little ripple of joy around the world. Friends and I exchanged excited texts. When she had her baby a few months later, it made me so happy that I did a little celebratory dance alone in my living room. Because becoming a mother — whether your child is still with you or not — is something to celebrate, no matter what.

Carol Smith is the author of “Crossing the River: Seven Stories That Saved My Life, A Memoir.”

A version of this essay also was published by The Washington Post.

Related video: