When Melissa Hogan's son Case was 2, doctors diagnosed him with Hunter syndrome, a rare genetic disease with a terrible prognosis: children with Hunter syndrome gradually lose the ability to walk, talk and eat, and most die by their teen years. There is no cure.

At least, not yet. Hogan's shock soon turned into determination: she promised herself she would find a cure. Next week, she faces a fundraising deadline for a clinical trial that might be her best hope.

“I was totally devastated,” she told TODAY. "I am very methodical and data driven. I approached it like everything, with research."

Hogan was a lawyer, not a doctor or a professional fundraiser. Hunter syndrome is what's known as an "orphan disease" — it's so rare that not much research is devoted to it.

This orphan disease got a mother. Hogan kept detailed spreadsheets listing Hunter syndrome research projects, their funding needs, and their likelihood at making a real difference. She founded a nonprofit, Project Alive, to fund a cure. After several years of searching, she discovered one gene therapy that may have the potential to treat and possibly cure Hunter syndrome.

“What we hope conservatively is to stabilize kids at the level they are at now,” she said. “We feel like if they are given the treatment early enough … they would not even develop the effects of the disease.”

Hogan's son Chase can't participate in the trial she's raising money for, because he's already in another research trial. But she isn't slowing down.

Project Alive is raising money to develop and manufacture the vector, the mechanism that helps the gene therapy get into cells. The organization has raised $650,000 of the $1.5 million needed for this step, which is essential to take it to clinical trails. Hogan hopes people will donate as Project Alive faces a funding deadline next week.

"It seems so easy to save kids’ lives and we just want to believe that people want to do that," Hogan said.

Only 500 children in the United States and 2,000 worldwide have Hunter syndrome, overwhelmingly boys although a few girls have it also. Children with it lack an enzyme that helps the body clear itself of cellular waste. There’s no cure and most with Hunter syndrome die in their teens from respiratory or heart problems.

"That, for me, personally was the hardest part … watching Case deteriorate and burying him at 12, 13, years old," she said. "We can accept physical challenges, the cognitive challenges, but the idea of him disappearing and dying is just horrific."

At 2, Case started experiencing constant runny noses, ear infections, and fell a lot. At the same time his facial features gradually began changing and his development slowed. But these symptoms were so subtle that Hogan gave them little thought. But her mom, Jane Hancock, did.

“My mom actually diagnosed him,” Hogan said.

Hancock, a registered nurse, was watching a TV show about a boy with Hunter syndrome and realized Case experienced the same symptoms. After she told her daughter, Hogan researched it and knew her mom was right.

“It’s pretty miraculous that my mom saw that,” Hogan said. “He wouldn’t have been diagnosed without it.”

While this led to early diagnosis, Case's future sounded bleak. There was no treatment and it was always fatal. But Hogan didn't give up.

“It really consumed my whole life. I probably wasn’t a great parent at that time but we were trying to save our kid,” she said.

She took Case to North Carolina to enroll him in a clinical trial. The study rejected Case because he wasn't sick enough.

“They needed a child who was declining to see if it worked,” she said.

Frustrated, the family returned home to Nashville, Tennessee, and watched Case worsen.

“He lost 18 IQ points when he was 3. It was a devastating decline. We watched him going from nine-word sentences to heavily stuttering to three-word replies and one word,” she said.

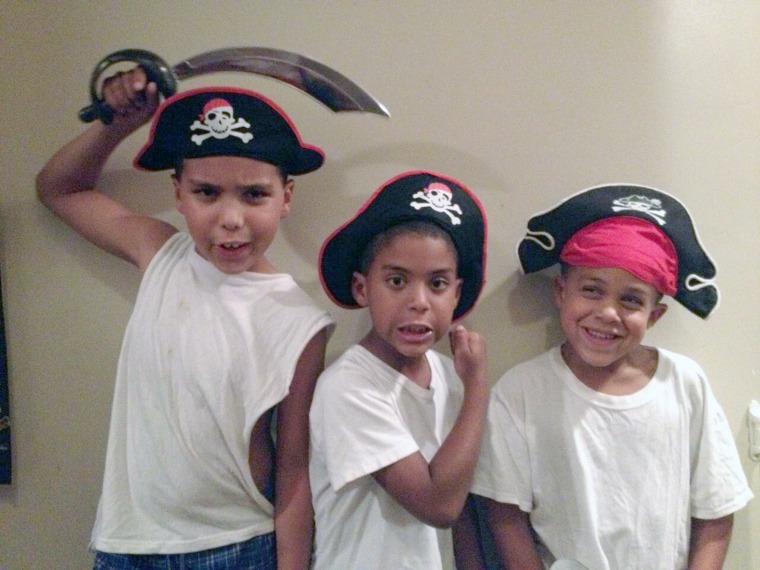

The North Carolina trial eventually accepted Case and the treatment seems to have stabilized his health. Now 10, Case loves playing basketball and tag and enjoys making friends at school. But the Hogans don't know whether it will extend his life.

Even though Case qualified for the trial, others did not. Hogan couldn't live knowing that other children wouldn't have the same chance as Case.

"That is why we started the gene therapy research," she said.

Hogan had learned that researchers had found a gene therapy for Sanfilippo syndrome, a sister disease of Hunter syndrome. She felt convinced that gene therapy could help children with Hunter syndrome and dedicated Project Alive efforts toward gene therapy. Suddenly, a remedy seemed real.

"Gene therapy has the potential to be a one-and-done cure," Hogan said. “If this works as expected, this would allow them to make the enzymes on their own."

The researchers need $2.5 million, total, to take their research from clinical trials to a treatment. While raising that much money can seem overwhelming, Hogan and other parents like her are determined to do whatever it takes.

"Cures are really possible," she said.