On Tuesday morning, at 8:24 am local time, a man wearing a gas mask threw a smoke canister and opened fire on people riding a Manhattan-bound N train as it was pulling into the 36th Street Station in Brooklyn, New York.

A reported 10 people were shot and six others were injured.

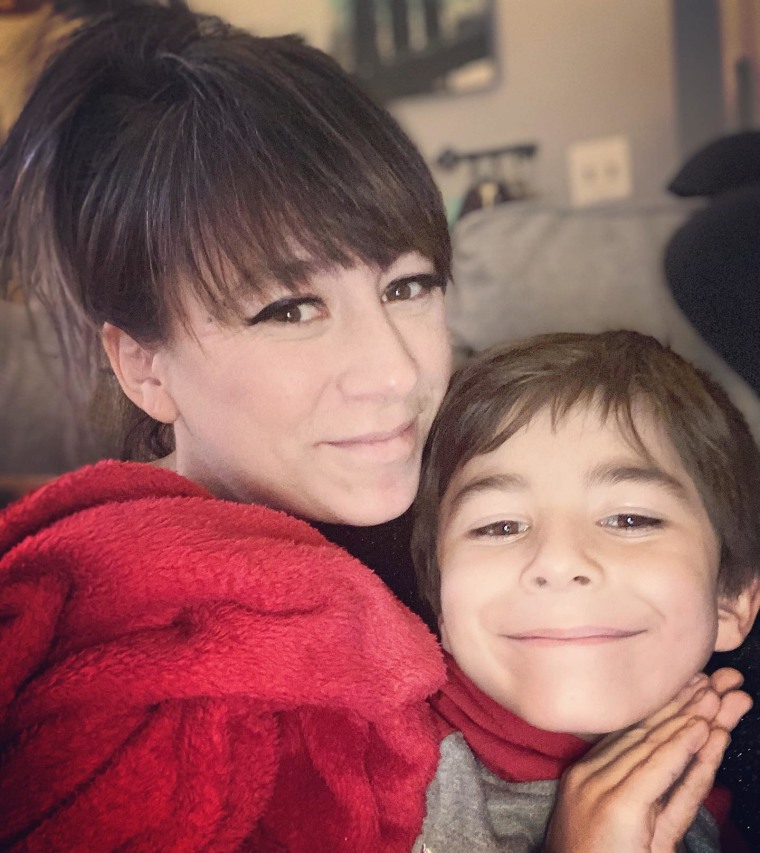

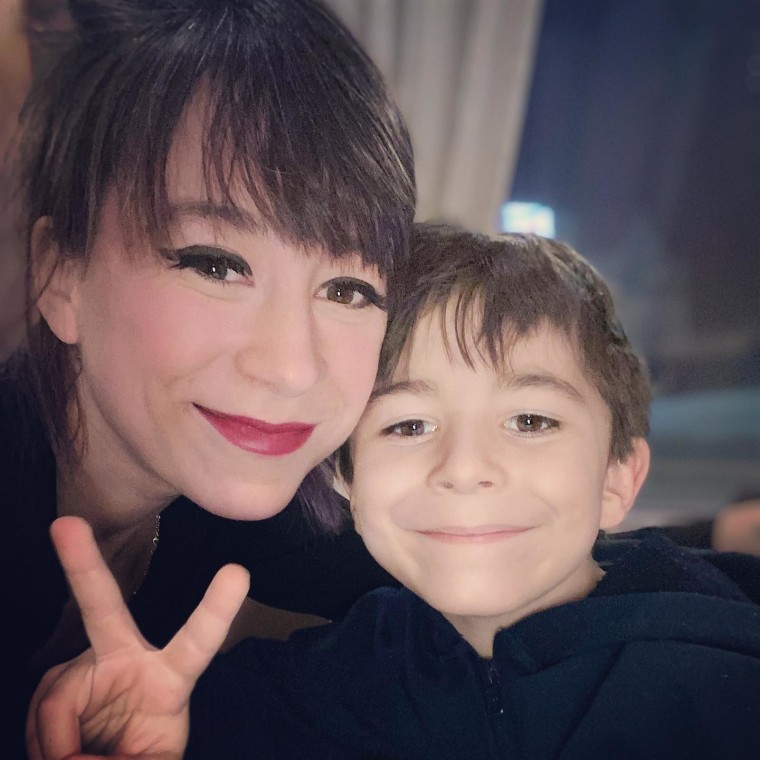

I live in Brooklyn, along with my partner of almost 9 years and our two sons, ages 7 and 3. My son goes to school near the shooting — not near our house, but we stomach the nearly hour and a half commute, every morning and every afternoon, because our son's school is that wonderful. We used to use that train station.

Like so many mothers in this ongoing COVD-19 era, I was working from home when the breaking news coverage screamed across my television. I was writing about the ongoing violence of Russia's war in Ukraine. Suddenly, a different kind of violence came to my doorstep.

A mass shooting occurred at a subway station in Brooklyn.

Ordinary citizens were performing first aide on their fellow New Yorkers as they bled on the subway platform.

People fled the train, screaming, while others stopped to document the terror.

The shooter is still on the loose as I write this.

Moments later, I received an email from my son's school: Out of an overabundance of caution, the children were "sheltering in place." This meant no one could enter or exit the building until the lockdown order had been lifted.

To be clear, my son was safe. He would remain safe. I knew this, logically. I told myself this fact over and over again as my anxiety increased. My stomach started to knot; I picked at the skin on the sides of my thumbs; I could feel my chest grow heavier with every breath.

He is safe. He will stay safe. He will be safe. He is safe.

But there is nothing — no amount of logic, no facts, no accurate news report — that can quell the instinctual, biological and evolutionary response of a parent who just wants — needs — to have their child in their arms.

A common description of parenthood is the notion that once you have a child, your heart exists outside your body. In many ways, that's painfully accurate, but I don't believe it fully encapsulates the experience of motherhood.

Having a child is also facing the manifestation of every fear you've ever had. You see danger everywhere — on the corner of a coffee table; an unfortunately placed door knob; the cleaning supplies under your sink; the wayward basketball bounced too close to the street — and somehow continue to live your life.

Motherhood is resilience. It's finding the courage to let go so your children can live and explore and dream and learn, while hoping — in a country where mass shootings have become far too common — that they'll come back to you alive.

Parenthood is forcing yourself to be optimistic for the sake of your children, and quell your pessimism borne out of the reality of the horrors of the world you work so tirelessly to shield your child from.

I paced my living room floor, contemplating the consequences of driving to my son's school and demanding they let me take him home. My friends, my mother and my partner urged against it — he's safe; protocols are in place for a reason; school officials know what they're doing; jail is bad.

Yet the knowledge that I could not get to my son was debilitating. I wanted to scream. I wanted to beg. I wanted to tear the walls of my child's school down until they let me take my baby home.

I thought of nothing else than getting to my child. Nothing, except all the other parents who have felt this way before and who, without common sense gun reform, will undoubtedly feel the same again.

I thought of Manuel Oliver, who lost his son, Joaquin "Guac" Oliver during the Parkland school shooting. Did he pace the living room too? Did he run towards the school, demanding they give him his son?

I thought of Fred Guttenberg, who lost his daughter, 14-year-old Jamie, in the same shooting. No wonder he yelled at former President Donald Trump during his State of the Union address. Of course he fights tirelessly for his daughter now. How could he not? I was angry at the mere thought of my son feeling afraid. Of his normal school day being disrupted in any way.

His daughter died.

Did the 26 parents of those killed in the Sandy Hook school shooting think about driving to the school? Did they pick at their thumbs, wondering how their children were feeling? Did they will the worst-case scenario from the corners of their brains, only to be destroyed by their reality? Did they think of the parents who have been where they are, too?

How did all the parents who were able to hug their children as I was — who did not have to identify a body but instead get to tuck a squiggly one into bed at the end of the day — feel? Relief, yes, but what about guilt? How do we cope with being thankful — happy even — in the midst of so much violence and trauma?

I used to take that very train to drop my son off at school, his younger brother strapped to my chest as my firstborn held my hand. I am thankful we no longer do.

I am enraged that I feel "thankful" that my family wasn't gunned down on our way to school drop off, as if it is a privilege to not be killed during your morning — perhaps more aptly named "mourning" — commute.

Mothers are not a monolith, and there are no two identical parenting experiences. But in a country where, in 2019, a child or teen was killed by a gun every 2 hours and 36 minutes, I believe this feeling — this "I must get my child; I must keep them safe; I am the mama bear ready to fight the world to protect my bear cubs" feeling — is universal.

We know it when we feel it. We see it in the faces of the parents around us. And more than anything else, we wish it would stop.

Related: