TODAY.com is re-sharing this essay in light of news that Catherine, Princess of Wales, is undergoing chemotherapy after she was diagnosed with cancer. In a video shared on social media, the former Kate Middleton addressed a part of the process that many parents with cancer struggle with: how to talk about it with their children. “It has taken us time to explain everything to George, Charlotte and Louis in a way that’s appropriate to them, and to reassure them I’m going to be OK,” she said. Writer and cancer survivor Julie Devaney Hogan shares what worked for her family in the following essay.

“That’s a really good question,” is not what you want to hear when you ask your doctor, “What the hell do I tell my kids?” after being diagnosed with cancer.

But that’s what I heard, along with a collection of other unhelpful non-answers from various experts, including but not limited to:

“Well, it really depends.”

“There’s no right or wrong answer.”

And my personal favorite …

“Only you as their mom will know what to say.”

“Really? Because I do not know what to say and I would like some help,” was my answer to that last one.

After I was diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer in late 2022 and began researching how to tell my children, I felt like the internet and social workers were reading me bad fortune cookie one-liners.

I also found lots of conflicting information.

“Tell them it’s cancer.” “Don’t use the big 'C' word.”

“Prepare them for all possibilities.” “Don’t tell them anything they don’t ask about.”

Don’t millions of people have cancer? How did we gloss over getting this part of the hell ride right? In addition to the information being insufficient and confusing, the content itself struck me as stark. I bought all the books, read all the jargon-filled pamphlets, yet I couldn’t see myself in any of it.

“Mom will be sick.”

“Mom will be bald.”

“Mom won’t be the same for a while.”

For a minute I wondered if I was in denial. Early in the journey I still felt like myself, and I knew that would change, but I certainly didn’t envision myself becoming the same frail, pale, bedridden pencil figure illustrated in the books I was supposed to show my kids. Every image of a mom with cancer reminded me of the grandparents laying in bed in "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory." Couldn’t they at least draw my future sad sick self in these terrible books in something other than beige pajamas?

Weeks into my diagnosis, people in our life were starting to ask me, too. “Do the kids know? How are you going to tell them?”

It struck me that there was no playbook, so I started to piece together something that was more aligned with the authenticity and truth I wanted the conversation to have. I worried the wrong words would instantaneously evict innocence from their souls, immediately catapulting them from the blissfully naive kids they should be at 3, 6 and 8, and into little people with heavy, burdened and scared hearts.

I decided if this was the fight of my life, I was telling my kids my way.

My husband, Dave, and I first talked about what we didn’t want. I had a list of 3 things:

- We didn’t want it to feel like a bad TV movie. Eating dinner, the sound of forks on plates, a bomb dropped by parents starting with, “Kids, Mom has some news to share,” children traumatized. We’ve all seen that scene. I didn’t want that scene.

- We didn’t want the conversation to be about mom being “sick.” My mindset since diagnosis has not been that I’m sick, but that I’m healing.

- We didn’t want any secrets or panic. In our house we say “secrets make you sick,” so we agreed that we’d tell them the full story in a way they could understand and also be able to talk about themselves. There isn’t a lot of “non-panic” language when talking about cancer. Words like cancer, chemotherapy, radiation and mastectomy are pretty heavy. We’d have to get creative.

Knowing what we didn’t want, we needed to land on what we were actually going to say.

As someone who has worked in marketing, consulting and technology my entire career, my love language is a slide deck. In my professional life, it’s how I tell stories. I’ve spent many all-nighters “building decks” for big meetings — I was going to do the same for my family. I found a template and got to work on the most important presentation of my life.

I decided to personify my sickness and boil down an executive summary story for my kids.

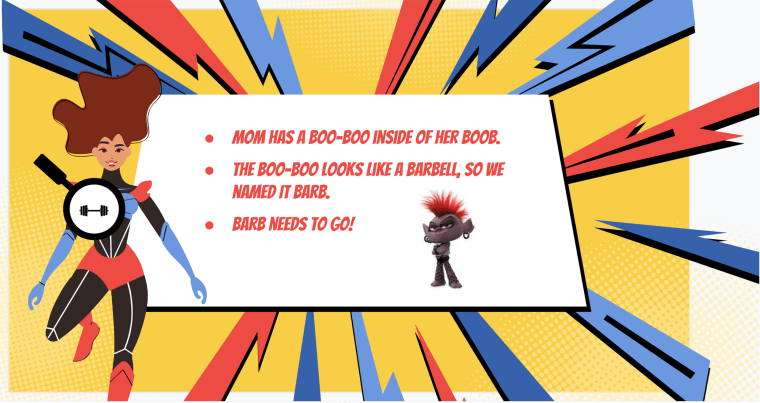

We named the barbell-shaped tumor in my breast Barb. Barb was a boo-boo villain in Mom’s boob, and Barb needed to go.

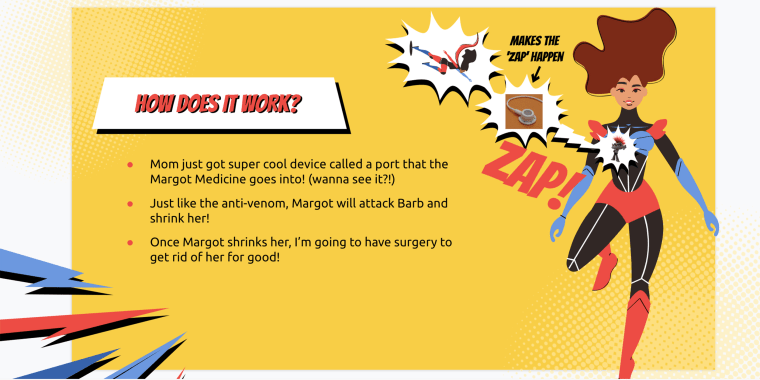

The acronym for the clinical trial drug that I was going to take was MARGOT, so Margot was my superhero. I’d be heading into Boston every week to get special Margot medicine through a magical tool called a port, and this would help shrink Barb.

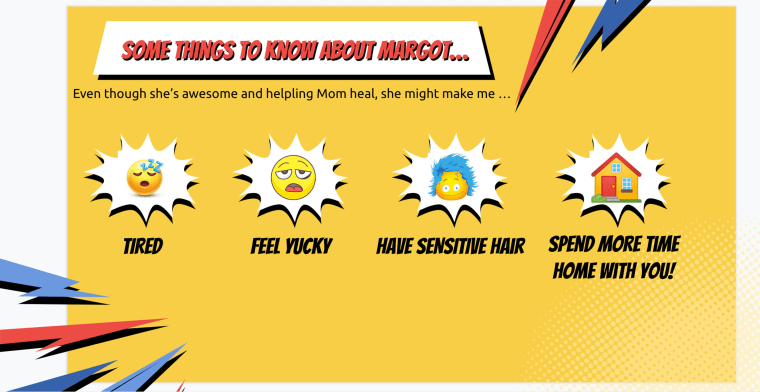

The slides I showed my kids:

We chose a Saturday morning to have “the talk.” We were purposeful about the day and time so the kids had the whole day with us if they had questions (not off to a school bus) and also not so close to bedtime that their little minds could race alone. In heavy avoidance of the sad TV movie scene — while we were around a table, there was no meal — we were playing a game together, something we frequently do. A funny one, too (Kids Against Maturity — I highly recommend it). The mood was light and we were laughing.

No sad sounds of forks on plates.

I presented the slides to the kids after we wrapped up our game, telling them I had something I wanted everyone to know about. We introduced Barb and Margot, and talked about the side effects of Margot, and what would happen in the weeks and months to come.

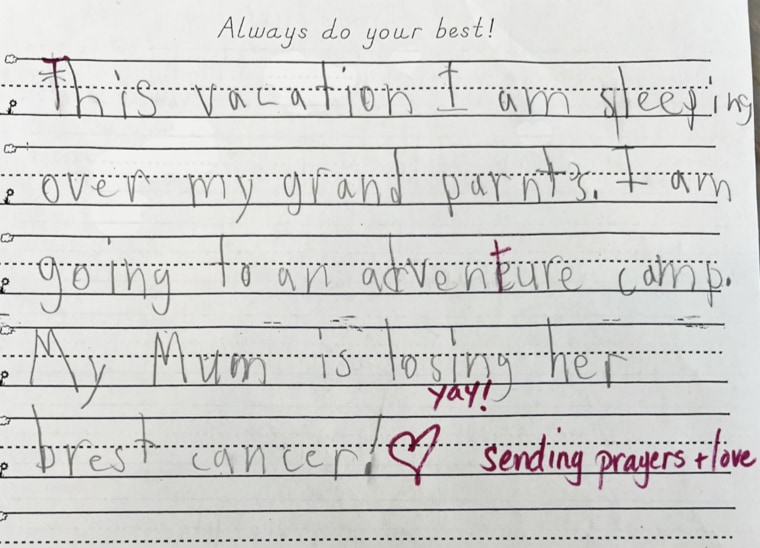

Bringing to life the cancer that was trying to take my life was ironically empowering. By doing this, you don’t hear us talk about “Mom’s cancer” much in our house. We talk about Barb (and hearing their little Boston accents say "Barb" makes me smile).

There are two words we decided to omit from our slides: cancer and death.

We wanted to give our kids the most important stuff first (what’s happening, what to expect), and decided we’d answer questions when they brought them to us.

A few weeks later, my 8-year-old asked me if Barb was cancer.

“Yes, she is,” I told him. He then asked how we’d get her out during surgery, if she had legs and if I could keep her in a jar.

“Can I still call her Barb, though?” he asked.

“Yup, that’s who she is,” I told him. “She’s Barb.”

Last week I underwent a double mastectomy. As my middle son puts it, “Barb has buzzed off.” I had trace amounts of cancer remaining, but the majority of Barb (and the friends she made in 7 lymph nodes) is gone, as a result of the chemotherapy I received before surgery. I will start low-dose chemotherapy and radiation as an insurance policy to make sure nothing comes back. We told our kids, “Barb is gone — now we burn her house down so she can’t come back!”

The question I haven’t been asked is, “Could you die?” It’s a question I dread more than my treatments and surgery, one I know is coming, and one that truly does not have a right answer.

While my prognosis remains curable, aggressive stage 3 cancer leaves me in a place where the unknowns can erode you quickly if you don’t quiet them. I don’t want my kids to carry that, and I also don’t want to lie to them.

My planned answer is, “I don’t plan to!”

And that’s the authentic truth.

Do you have a personal essay to share with TODAY? Please send your ideas to TODAYEssays@nbcuni.com.