Their faces fill my screen, expressions of hope and expectation on their 10-year-old faces. I stare into their bright eyes until my hands begin to shake. I have to look away to get a breath. It’s been three weeks since 19 children and two teachers were killed at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, right before classes were to let out for summer.

Little more than a week earlier, 10 people going about their business were shot dead in a racist rampage at a Tops grocery store in Buffalo, New York. Since then, there have been more than 60 mass shootings across the United States — so many of them, it’s getting harder to recall the details of each. They come and go with fierce regularity, claiming victims at churches, schools, stores, restaurants, parties, subways and shopping malls.

When the most notorious shootings happen, we go into collective mourning, rapid cycling between rage and anguish. We light candles and make speeches. We hug strangers. We cry and whisper our despair. It’s too much sadness. Too much, we say. And then our sadness, the sadness of strangers, begins to fade as it always fades. This is how collective grief works. Over time, the faces blur. The tragedies begin to bleed into one another.

It takes only a week for that to happen. According to research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences about the effect of mass tragedies on daily emotions, “the impact of mass shootings (even in the most extreme incidents) is close to zero within roughly one week of the event.”

One week.

Public grief vs. private grief

There’s a difference, though, between collective and individual grief.

Collective grief provides us catharsis, allows us to purge our feelings. We move on for self-preservation, and so the business of schools, churches, grocery stores and shopping malls can keep going.

For the loved ones of the victims, though, there is no catharsis. Not yet. For some, not ever. When the public mourning period ends, the private one is just beginning. Maybe it’s this disconnect between the experience of public and private mourning that has given rise to one of the most damaging myths surrounding grief — that it should end after a year and if it doesn’t, there must be something wrong with you.

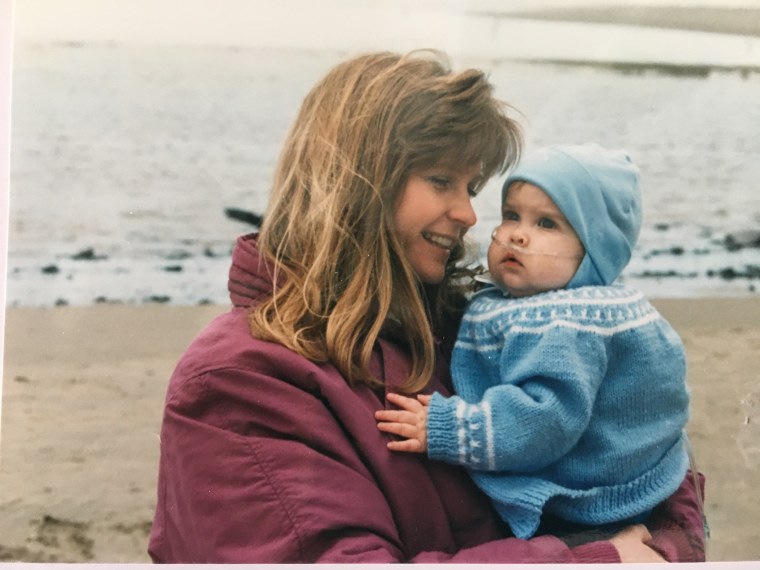

I lost my only child more than 25 years ago, and I still think about him most days. For years, though, I couldn’t admit that.

Related essay: When you’ve lost a child, Mother’s Day is Memorial Day

I’m fine, I said when people asked how I was doing.

I said this in the first year because I was in shock and didn’t have the words to begin to describe what I felt. My son was 7 when I got the phone call that he’d died unexpectedly while visiting his grandparents. The fact I wasn’t there to hold him in his last hours haunted me.

I said it in the second year because by then I’d instinctively absorbed the message that it’s not culturally acceptable to continue to talk about deep sadness more than a year after a loss. It makes people uncomfortable, as though they should be able to do something; it makes them feel helpless.

I said it year after year to convince others I was OK and to convince myself. It worked, for the most part. Three years after my son’s death, I went back to my job as a journalist for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. To the outside world, it looked as though I were “over it.” In reality, I was living in my own private snow globe — watching the rest of the world pass by without engaging. I avoided relationships, both old ones and new, so I didn’t have to talk about it.

‘No, I don’t have children,’ I said for years if strangers asked. This would later send me into a spiral of shame and agony.”

No, I don’t have children, I said for years if strangers asked. This would later send me into a spiral of shame and agony. “No” felt like denying he had ever lived. My giggly little boy with eyes the color of maple syrup. My boy, who loved trains, and tee-ball, and “101 Dalmatians.” My son, who was deaf and helped me see both language and the world around me in a brand new way. My son, who pressed his hand to mine when we signed, I love you, and whose hugs I sometimes still feel in my dreams. “Yes” forced me to explain he was dead and brought up memories that were still too painful to face.

These lies kept me frozen for many years.

Related essay: Closure is a myth: Getting through Mother’s Day without my child or my mom

Prolonged grief disorder

It wasn’t until more than two decades later that I learned there was a name for what I likely experienced: prolonged grief disorder.

Recently, the American Psychiatric Association officially included the diagnosis in its "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)." It refers to intense emotional pain that persists more than a year after a loss. Some of the criteria include:

- numbness

- withdrawal

- an inability to rejoin the normal stream of life.

Those who lose children are at particular risk, as are those who lose a loved one to violence, natural disasters and other tragedies.

The official inclusion of the diagnosis caps years of debate over whether labeling something "prolonged grief disorder" amounts to pathologizing grief. None of us escapes without losing something or someone we love dearly. The process of grieving a loved one is as individual and idiosyncratic as the person who has died. Critics of labeling long grief a disorder argue that to suggest otherwise is to indicate that a normal process is a disease. But lost in all this heated discussion is what it’s like to live with deep grief year after year.

We are taught to suck it up. We are taught to power through. We get our few days of “bereavement leave” and then we’re supposed to get back to work. There’s not much of a grace period when it comes to grief. And because of that, long-term grief has been invisible to those who most need to recognize it.

Related essay: Grieving mom shares how she gets through the holidays

During the pandemic, I attended a virtual conference for families who have lost children. One of the other bereaved moms gave a presentation about complicated grief. She ticked through some of the signs and symptoms:

- intense yearning that interferes with normal life more than a year after the death

- numbness

- disbelief

- avoidance of social contact

- difficulties moving on.

It was as though she were describing my life in the 10 years that followed my son’s death. For the first time, I didn’t feel inadequate for the difficulties I had adjusting to the loss of my only child.

I was never officially diagnosed back then because such a diagnosis didn’t exist. At the time, I didn’t even associate many of my behaviors with grief. Neither, apparently, did those around me. No one back then suggested that my growing social anxiety, my persistent nightmares or my general paralysis in life might have been because of grief. And because of that, I never thought to ask for help.

I wish I had. I believe it would have made me feel less alone — less “defective,” not more so. I eventually found my own path forward through my work as a reporter. I immersed myself in stories of hope and transformation, which in turn helped me come to terms with my grief.

But I wonder, now, if I could have reached a place of peace with my loss sooner. I don’t think the new diagnosis pathologizes grief so much as makes it visible to those who suffer it and to those in their lives who might be able to help. Maybe the best thing that can come from the new diagnosis is not the view that long grief is disordered or maladaptive, but that it exists for some, it’s a normal response to an abnormal situation, and it deserves our compassion.

Related essay: I will never stop being a parent, even though both my children have died

We often say of parents who have lost children that they will never be the same. This is necessarily true, as it is for anyone who has suffered a profound loss. But it doesn’t mean that we can’t eventually integrate that loss in such a way that life has meaning and joy again. To get there, though, requires all of us to be more aware.

Recognizing when someone’s behaviors might be grief-related, even years later, could encourage more of us to talk about it. It might make it OK to say, yes, it still hurts, when someone asks how we are doing. It might make it OK to get a little help. And it might make more of us offer it.

The families who lost children or loved ones in Uvalde have a hard grief road ahead of them. They are going to need help long after our attention pivots to the next extreme public tragedy. Let’s not look away. That’s the least we can do with our collective grief.

Carol Smith is an editor with NPR affiliate KUOW Public Radio in Seattle and the author of “Crossing the River: Seven Stories That Saved My Life, A Memoir” (Abrams Press, 2021). Connect with Carol on Twitter @clsmith321.

Related video: