Perhaps it was because we’d already been together 10 years, or that I didn’t have a binder filled with floral arrangements, sample menus and gowns clipped from magazines, but in the days following my partner getting down on one knee, placing a ring on my finger and us agreeing to grow old together, I struggled to feel like a bride.

After grocery shopping the following weekend, I wandered into the bridal salon at the other end of the shopping center.

“Just looking,” I advised the salesperson, who’d already made their way out from behind the counter.

“Totally get it,” they nodded, continuing to give me the dime tour before parking in front of a single rack of red gowns. “So, these are the only samples we currently have in red, but there are some designers who offer a red option. Just let me know if you see anything you want to try on!”

Not only had they mistaken me for being Chinese, but they had also assumed the Chinese wedding tradition of wearing red — which symbolizes luck and prosperity — belonged to me.

*

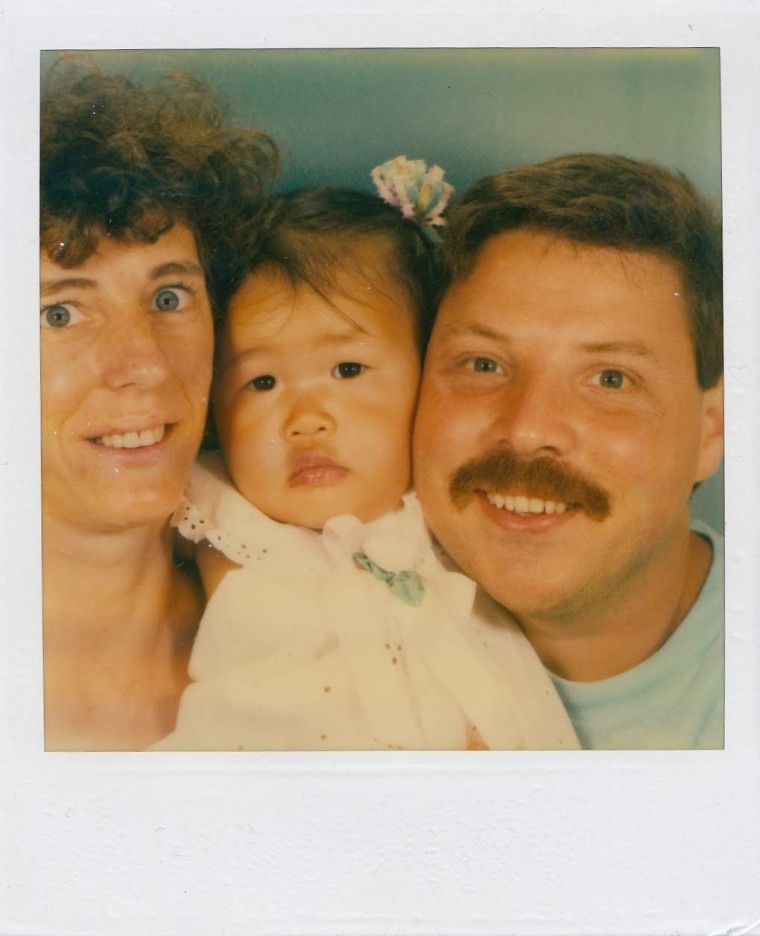

I spent the first three months of my life in a South Korean orphanage before I was adopted. From a young age, the dominant adoption narrative was impressed upon me as gospel. Friends, family, and strangers would tell me how lucky I was to be adopted, how my adoptive parents were giving me a better life — and how much they had sacrificed and suffered to give me that life. As a result, I came to understand a condition of the life gifted to me by my adoptive parents was gratitude. And the way to show gratitude was through absolute loyalty to them and refusing to acknowledge all the things that made me different.

Being an adoptee means existing in the in-between. I live in between how the world sees me and how I see myself, in between the life I live and the life I could have lived, in between the family I have and the family I lost. As a transracial adoptee — a person who is adopted by parents of a different race — there’s also another in-between. Despite identifying as an Asian American, I am not fully accepted by either the Asian or American communities.

Whenever I meet Asian people, they know I’m not one of them. I can feel it as soon as we make eye contact. I can’t explain it — they just know, and I know they know. My first Asian friend laughed when I told her I was Korean and said, “Girl, you’re a Twinkie.” Yellow on the outside, white on the inside. It was the first time I’d heard the term, and when I began to explore my identity as a transracial adoptee.

People say you can study Korean history, cook and experience Korean cuisine, that I can travel “back there” and “see what it’s like.” But no matter how much history I study, food I taste or Rosetta Stones I take, Korea and all its wonder will never belong to me, never be part of me. Korea never did, never was.

*

After showing my future mother-in-law, “M”, the engagement ring her son had presented me with two weeks before, she took me in her arms and said, “I’m so happy to call you my daughter.” One of the first things I learned about M was that she was a hugger. Everything came easy with M — we swapped recipes and gossip, and she had even offered to teach me how to make sauce one Sunday. As far as mother-in-laws went, I knew I’d hit the jackpot. Yet, when she told me I could call her “Mom” if I wanted, I suddenly felt as though I was on the verge of crossing a line, and that once I did, I might never be able to go back.

The woman who raised me, whom I call “Mom,” will always be my mother. However, she is not my only mother. My first mother — the woman who carried me and brought me into this world — was, and likely will remain, unknown to me. When I think of her, she doesn’t even have a face — she is simply a specter, more like a shadow than anything else. Yet, she is undeniably real.

My relationship with my mother is constantly evolving. Throughout adolescence, there were a lot of screaming matches, slammed doors and periods of silence, which spilled into my adulthood. We struggled to understand each other, to communicate, to convey our love for each other without trying to control or change each other. While we are in a better place now, we have had to work at it, and the work has been anything but easy.

As a teenager, I found an ease with everyone else’s mothers but my own. Friends’ moms seemed to love me. Being with them was easy in a way being with my mother never was. And while, at first, I would embrace it, guilt eventually took over.

Adoption and its processes are a series of agreements and contracts. Most adoptive and birth parents all know they’re agreeing to something, but it falls to the adoptee to carry the burden of meeting the expectations attached to those agreements. Being an adoptee has sometimes felt as though I’d inherited an oath, a debt I’d never be able to repay. Someone had pledged my loyalty on my behalf, and I couldn’t escape it.

When my partner proposed, I knew he wasn’t just asking to grow old together — he was asking me to join his family, to be part of his tribe, to belong.

They say you don’t just marry a person, you marry their entire family. When my partner proposed, I knew he wasn’t just asking to grow old together — he was asking me to join his family, to be part of his tribe, to belong. And while I said “yes” wholeheartedly, I can’t help but think about the mother, the family, the life that discarded me, that I never knew and may never know. I wonder how many new sons and daughters they have welcomed into their tribe, and if they ever think about me.

I often wonder what my life — what I — would look like had my biological mother not relinquished me. I wonder if we have the same laugh, if I’m built more like my biological father, if I have my grandmother’s discerning stare. I wonder what traditions we’d be embracing as we prepare for my wedding. I Googled “Korean wedding traditions” but realized I couldn’t tell which ones were authentic. After all, how would I know?

It took a long time to understand multiple things can be true at the same time, and that love isn’t mutually exclusive. Being curious about my birth parents, and where I was born, does not mean I don’t love my adoptive parents and where I grew up. Being Korean does not make me less American and being American does not make me less Korean. And embracing a new family does not mean I am turning my back on the family that has loved me my entire life.

And so as I prepare to walk down the aisle — into a new phase of my relationship with my partner, into a new family, into the future — I am constantly reminding myself that I know who I am, that I am capable of finding balance, and that love isn’t finite.