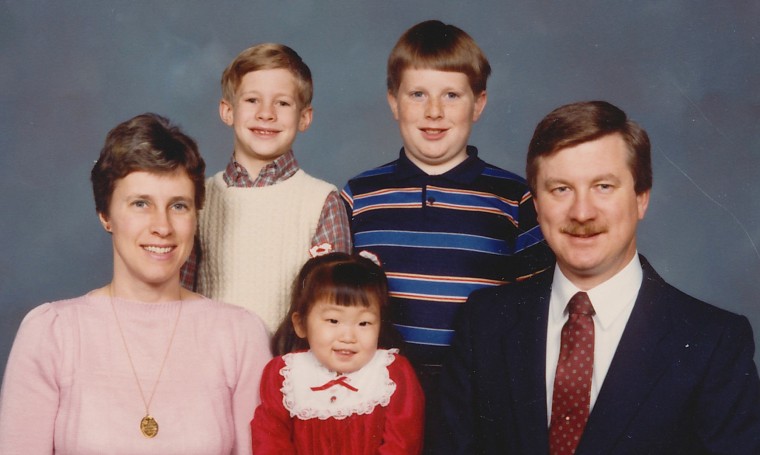

Whenever I look at my adoptive family, I see my dad’s full head of hair in my oldest brother. I see my mom’s rounded nose in my other brother, and they all share blue eyes.

When I look at my reflection, I’m proud of my dark, almond-shaped Korean eyes, and I love my tiny nose that can barely support a pair of sunglasses. I’m sporting a few gray hairs at 36 years old, and my neck reminds me that orthopedic pillows are essential. But when I take a second glance at myself, I do not see any of the features my family shares.

I’m often asked if I remember anything about my time in Korea and always laugh when answering no, because I was adopted at 3 months old. I hesitate to even use “adoptive” when describing my parents, because they’re the only ones I have ever known.

As for my biological parents? I’ve never felt a need to dig up their identities. I am an advocate for adoption and view their decision as an act of love, one that allowed me a lifetime of opportunities.

However, if I must pinpoint one facet of my adoption that bothers me, it’s that I don’t share any physical similarities with my family. I’m certainly not wanting to transform myself into a Caucasian woman by any means — if I had been adopted by a Korean family, I would still feel this same pang. My brothers have features of my parents permanently embedded in them and can carry on a physical legacy that I have to observe from afar.

That said, I’m proud of my heritage and race. My parents discussed my adoption at a young age, and so I always knew that I was Korean. But it wasn’t until elementary school that I became acutely aware of my own physical appearance. One afternoon, as my friend and I studied our reflections in her vanity mirror, I noticed how her eyelids almost disappeared when she opened them, and I was fascinated by the darkness of my irises.

When I was in fifth grade, I remember telling my mom that I wanted to look like her. I didn’t want my mom’s eyes because of her race. I wanted her eyes because she was my mother, the person I wanted to emulate. I also fantasized about her having my Asian eyes and black hair. In my young mind, I thought that would make us more alike and therefore more connected.

My mom always responded that we didn’t need to look alike, and her love was the same as if she had given birth to me. In fact, she said it was stronger, because she went to great lengths to find me from across the world. My parents continued to educate me as best they could about my Korean ethnicity. They organized a variety of experiences and helped me pursue what interested me the most.

We bonded over stories about my adoption and, every year, watched the video of my “Gotcha Day,” the day I arrived in the U.S. I ate my way through cultural festivals, took classes, read my adoption papers and played with Korean dolls. We discussed tough situations and worked through instances of racism with educated, empowered responses.

When I reached adulthood, I wondered what it would be like to have children. Will they prefer playing with dolls or more with stuffed animals, like me? Will they go to college and major in writing? And I always felt a rush of hopefulness whenever I thought, "Will I be able to see a part of me in someone else?"

I always felt a rush of hopefulness whenever I thought, "Will I be able to see a part of me in someone else?"

I dated without much success into my early 30s and watched most of my friends have children. When I turned 33 years old, I no longer wondered when I would have kids — I wondered if I would have kids.

Would my age allow it? Does my lineage carry health problems? But I trusted in God’s plan and, right before the COVID-19 lockdown, I met a guy named Lee on a dating app.

We got married two years later, and I became pregnant with a little girl.

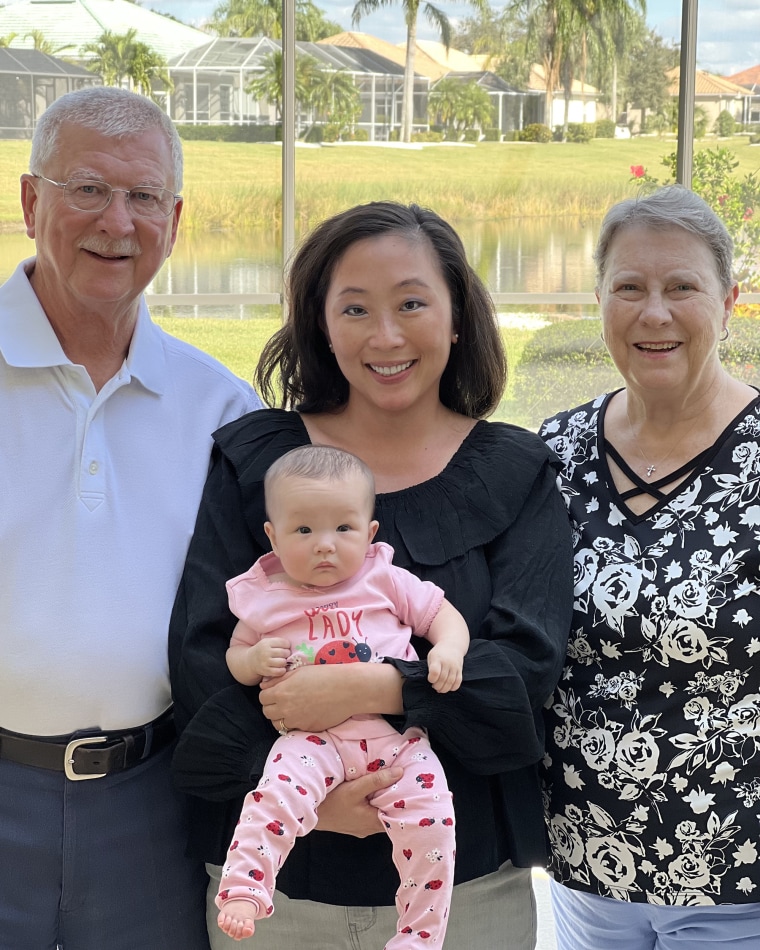

During my pregnancy, I was fascinated that I was growing a baby. I logged her first kicks and hiccups, and played “You’ll Be in My Heart” daily, the song I danced to with my father on my wedding day. Weeks before my due date, I laughed when sonograms showed her miniature Asian eyes, closed and smooshed against her hand.

My husband and I chose the name Lainey, a nod to the ladybug trinkets my mother and I collect, my real-life Lainey bug. And when Lainey was placed on my chest for the first time, I felt like I was floating in the ocean. I felt light and euphoric and at peace. I tickled the dark fringe of Lainey’s hair and smoothed my thumb over her eyelids, which were — finally — a part of me.

Lainey had felt my emotions from inside of me for nine months, and I wish she understood then, there on the hospital bed, that my tears were a culmination of 36 years of waiting for her.

In some ways, Lainey is the closure I have needed, and my husband says that I likely initiated a new bloodline in the U.S. But my bond with Lainey as mother and daughter extends beyond just her birth, which is the message my mother always tried to explain to me.

Now, I understand her words.

Every day, I bond with Lainey through each laugh, kiss and bedtime story. I look forward to our lifetime full of these moments, and I will teach Lainey all that I know.

I will pass on my hanbok, celebrate my Gotcha Day and take Korean classes with Lainey to help her explore her culture. I’ll always feel profound pride when looking at her and seeing her with my eyes, nose and cheeks. And while Lainey will never share my family’s eyes or my mom’s nose, I will lean on my upbringing to show Lainey that family resemblances include more than physical appearances. I will teach her about my dad’s work ethic, my mom’s ability to see the good in all people and their devoted faith — all traits I hope she too will share. I will show her the powerful bond of our love, which is the ultimate family legacy I want her to embody.

I will never have my identity fully figured out, much like with motherhood. But I do know that my love will carry Lainey for the rest of her life, even after I’m gone. I’ll continue to grow as I continue to learn — with Lainey by my side and in my heart.

Related video: