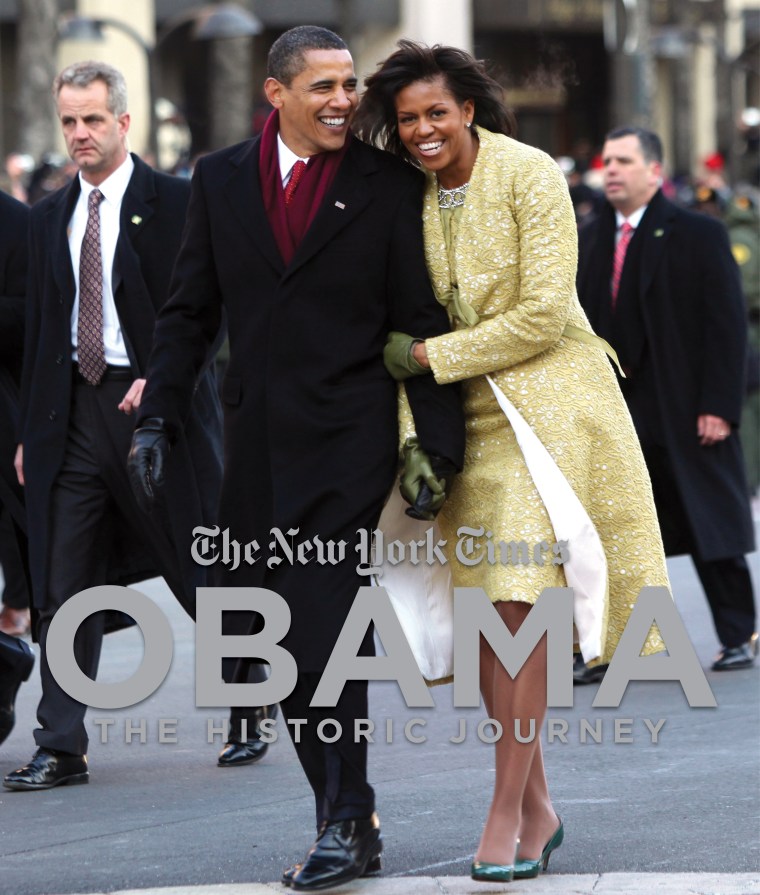

The New York Times has chronicled the exceptional moments of President Barack Obama's life though in-depth reporting, insightful analysis and visual imagery and combined them in "Obama: The Historic Journey," a comprehensive look at Obama's election. An excerpt.

Prologue: Winds of change

“I think it’s fair to say that the conventional wisdom was that we could not win. We didn’t have enough money. We didn’t have enough organization. There was no way that a skinny guy from the South Side with a funny name like Barack Obama could ever win ...”

March 18, 2004

The lines began forming weeks before the election: in Florida, where seniors feared there might be a repeat of the rampant confusion that marred the disputed 2000 voting; in Ohio, where unsubstantiated rumors swirled that polling places would shut their doors promptly at the appointed closing time, no matter if there were still lines of eligible voters waiting; in roadside casinos and laundromats dotting dusty Western highways.

The early voting lines were just one striking measure. In previous elections, some Americans had become blasé about their most precious right, but not this time.

Rutha Mae Harris backed her silver Town Car out of the driveway, pointed it toward her polling place on Mercer Avenue in Albany, Ga., and started to sing.

“I’m going to vote like the spirit say vote,”

Miss Harris chanted softly.

“I’m going to vote like the spirit say vote,

I’m going to vote like the spirit say vote,

And if the spirit say vote I’m going to vote,

Oh Lord, I’m going to vote when the spirit say vote.”

As a young student, she had bellowed that same freedom song at mass meetings at Mount Zion Baptist Church back in 1961, the year Barack Obama was born in Hawaii, a universe away. She sang it again while marching on Albany’s City Hall, where she and other black students demanded the right to vote, and in the cramped and filthy cells of the city jail, which the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described as the worst he ever inhabited.

For many black Americans like Miss Harris, now 67, the short drive to the polls on November 4 culminated a lifelong journey. As they exited the voting booths, some in wheelchairs, others with canes, these foot soldiers of the civil rights movement could not suppress either their jubilation or their astonishment at having voted for an African-American for president of the United States.

Hours earlier, just before 6 a.m., Kimberly Ferguson was 12th in line outside the Adam Clayton Powell State Office Building on 125th Street in Harlem. She was steps from the legendary Apollo Theater, where, in the fall of 2007, Barack Obama had spoken to an audience notably light on New York’s black political leadership, who were backing Hillary Clinton.

“I got here early so I could make it to class,” Ferguson said, shouldering a backpack of books with an orange peeking out of its side pocket. The Lehman College sophomore was part of a new army of young voters drawn to political participation through the Internet. All of her friends were voting, mostly for the first time, for Obama. “I want to be part of history,” she said, as she clutched her voter registration form and watched carefully as an elderly woman in a leopard jacket and black cat-eye glasses tinkered with the voting machine.

Everywhere, there was a sense of history being made, not simply because of Barack Obama’s meteoric rise, his unusual background and the campaign he ran but equally because the country was facing such daunting problems; a financial crisis like none seen since the Depression and two wars. Because so much was riding on the outcome, it felt like the world was holding its breath waiting for the vote.

At 7:36 a.m. banks of television cameras captured Barack and Michelle Obama as they arrived to vote, with their daughters, Malia, 10, and Sasha, 7, at Chicago’s Beulah Shoesmith Elementary School. A few nights earlier, on Halloween, the candidate had briefly lost his cool when the cameras came too close while he walked Sasha, dressed as a corpse bride, to a neighborhood party. From this point onward, the Obamas and their young girls would be the focus of the kind of celebrity glare not seen since the Kennedys.

This was one reason Michelle Obama had taken so long to get comfortable with the idea of her husband running for president. “Barack and Michelle thought long and hard about this decision before they made it,” said their good friend Valerie Jarrett. Michelle wanted her girls to have the kind of close family life that she and her brother Craig had enjoyed growing up on Chicago’s South Side. There had been all too few family dinners since February 10, 2007, when, standing in the shadow of Abraham Lincoln’s Old State Capitol in Springfield, Ill., Barack Obama had declared his candidacy for president and recognized “there is a certain presumptuousness — a certain audacity — to this announcement.”

Even Malia had found her father’s fast rise audacious. Visiting the U.S. Capitol shortly after his election to the Senate in 2004, she asked whether he would try to be president. Then a follow-up question so sensible it could only come from a first-grader, “Shouldn’t you be vice president first?” The Clintons and other Democratic elders grumbled that his experience was too slight to go up against a grizzled Republican veteran like John McCain. Vernon Jordan and other senior leaders of the civil rights movement implored him to wait his turn. Obama responded by quoting Martin Luther King Jr. on “the fierce urgency of now.”

Eventually audacity became more than hope, with poll after poll showing a commanding Obama lead. In the closing days of the election, the campaign plane touched down in red states that hadn’t gone Democratic since the Lyndon Johnson landslide of 1964 — even Confederate states like Virginia. Still, some commentators were continuing to warn about a so-called Bradley effect, where in the privacy of the voting booth whites who told the pollsters otherwise would never pull the lever for a black candidate. Top campaign aides worried that the Obama base was becoming overconfident. There were no sure bets in American politics.

On election night, Barack and Michelle shared a steak dinner at home, then joined their Chicago inner circle at a downtown hotel suite. There were the two Davids, Axelrod and Plouffe, the architects of the campaign’s field strategies and advertising respectively, as well as the communications director Robert Gibbs. Jarrett, who had served as a mentor to both Barack and Michelle and, like them, was part of Chicago’s black professional elite, embraced her friends. Children — the Obama girls and the grandchildren of Obama’s running mate, Joseph R. Biden Jr.— bounced around the room.

Some of the key battleground states had already been called, but as the urban areas of Ohio began coming in, the candidate turned to Axelrod, a former political writer for the Chicago Sun-Times, who had been with him since he had been in the Illinois Senate.

According to Newsweek, Obama said, “It looks like we’re going to win this thing, huh?”

“Yeah,” nodded the red-eyed consultant.

In anticipation of a historic acceptance speech, crowds had been gathering in Chicago’s Grant Park since daybreak.

Thousands of miles away, in the Kenyan village where Obama’s father was born and buried, men and women sat entranced. “We’re going to the White House,” sang the large crowd gathered there, swatting mosquitoes as they watched the election results trickle in on fuzzy-screened television sets.

The rest of the world watched, too. In Gaza, where the United States is held in special contempt, it seemed scarcely possible that there could be a country where tens of millions of white Christians, voting freely, might select as their leader a black man of modest origin, the son of a Muslim. There is a place on Earth — call it America — where such a thing could happen.

And in Albany, Ga., Rutha Mae Harris was waiting and watching at Obama headquarters.

Excerpted from "Obama: The Historic Journey" by The New York Times and Jill Abramson. Copyright (c) 2009, reprinted with permission from Callaway.