During Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, TODAY is sharing the community’s history, pain, joy and what’s next for the AAPI movement. We will be publishing personal essays, stories, videos and specials throughout the entire month of May.

This year, amid a surge in anti-Asian hate crimes and incidents, there is a sharper focus on the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. With the increased attention comes more scrutiny on the AAPI designation. After all, the AAPI term seeks to include and represent an outsized group of people hailing from or having roots in the largest continent on Earth, a region that includes nearly 50 countries.

Among Pacific Islanders, specifically, there’s a renewed debate about the inclusion of Pacific Islanders within wider AAPI initiatives and programs. Some argue that Pacific Islanders benefit when categorized alongside Asian Americans. Others say Pacific Islanders are underrepresented and should be separated because their issues and needs are different from those of Asian Americans. Yet another group, who have both Asian and Pacific Islander ties, are torn over the debate, unsure whether splitting up the AAPI grouping is necessary.

“We Polynesians don’t have any representation in the AAPI. I think it’s time we separate Asian American & Pacific Islander since this is becoming an ongoing problem,” a Twitter user wrote in a May 1 tweet.

“People have really strong feelings about combining asian & pacific islanders when talking about racism, which confuses me bc i’m half asian (filipino) & half pacific islander (chamorro)... i can’t separate the two, AAPI is just me,” tweeted another in March.

“What exactly is an 'AAPI' woman? Just say Asian American women, Pacific Islander women! We Pacific Islanders are indigenous to Oceania/Pacific & are not Asian! Terms such as 'AAPI, API Asian/Pacific Islander' flout federal laws (OMB Directive 15) to keep our groups separate!” another asserted, in response to a tweet from the American Civil Liberties Union about the gender wage gap and racial justice. The user's tweet referenced the White House Office of Management and Budget’s 15th directive which consists of standards for “maintaining, collecting, and presenting federal data on race and ethnicity.”

Who is considered Pacific Islander?

The federal government gathers and reports data for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders separately. In 1997, the Office of Management and Budget revised Directive No. 15 and divided the “Asian or Pacific Islander” racial classification into two separate ones — “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.” The change wouldn’t create a “new population group” but would expand government recognition of “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” as a separate racial category.

Anyone identifying as Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Northern Mariana Islander, Samoan, Fijian, Micronesian, Carolinian, Palauan, Papua New Guinean, Kosraean, Ponapean (Pohnpelan), Trukese (Chuukese), Yapese, Melanesian, Polynesian, Solomon Islander, Tahitian, Tarawa Islander, Tokelauan or Tongan would fall under the “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” classification.

Tavae Samuelu, the executive director of Empowering Pacific Islander Communities (EPIC), a national social justice organization based in Los Angeles, explained to TODAY that the definition of a Pacific Islander is complicated by multiple factors. “One, race is a social construct. So, 'Pacific Islanders' is constructed," she said. "Two, Pacific Islander is constructed a very specific way here in the U.S., that so many of the conversations I've had with folks … (in) international spaces, where, we have folks who are based in Australia or New Zealand who are like, ‘AAPI is not a thing here.’”

The definition, Samuelu added, is also shaped by years of U.S. colonization and militarism in the Pacific Islands and whether a Pacific Island nation has a formal relationship with the U.S. or not.

Dr. Lilikalā Kame’eleihiwa, a senior professor of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, defines Pacific Islanders as “the people whose ancestors were on those islands."

"If people have come in the last five or 10 generations, look, their ancestors are somewhere else, which is cool. That's fine, but they're not native or indigenous to the islands," Kame’eleihiwa told TODAY. "And to make sure that our own cultures never disappear, we have to make sure that we can stand up and say who we are.”

‘We need to have alliances’

Kame’eleihiwa, 68, who identifies as a Native Hawaiian, sees room for growth within the AAPI designation. “I think if there's only one question, 'Are you Asian American or Pacific Islander?' then that's not going to do very much good for people in the government who want to do the things we do for the people. I like that AAPI … that Asian American Pacific Islander term has been used in a way because there's a big network of people who are doing good things and are doing a lot of work.

"So the Asian community in America is much higher in numbers than the Pacific Islander or the Hawaiian community in America. And that means that we get to benefit from the work that Asians are doing on different issues about racism and bias, so that's a good thing."

But Kame’eleihiwa emphasized the AAPI term shouldn't be applied in all cases. “Now when it comes to the census, I think it should be broken out. I think Asians are not monolithic either. ... So you got Chinese lumped in with Indians with Indonesians, etc., that's such a big area. It's like saying all Caucasians are the same, which is what they do anyway, right?

"I'm not going to tell Asians what they should have, but for Native Hawaiians, we want to be counted separately on account of we want the country back. We want Hawaii to become an independent nation again. So we're always advocating for more control of our land, more control of our politics, more control of higher education. ... Our numbers are important to be counted. So we are Pacific Islanders, and we're happy to be Pacific Islanders."

We need to have alliances, and I think the alliance between Asians, Pacific Islanders, the Hawaiians is a good one.

Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa

Kame’eleihiwa added, “We have to have bridges. We need to have alliances, and I think the alliance between Asians, Pacific Islanders, the Hawaiians is a good one. It's a good alliance. The problem is when the American government doesn't want to adjust things once it's done.”

‘The long-term impact has been erasure’

Samuelu, 33, who is ethnically Samoan and the first in her immediate family to be born in the U.S., told TODAY the debate about using or not using AAPI as an umbrella term is a valid one. “I think, on its best day, AAPI is ambitious. It seeks to encompass the two largest areas in the world at minimum, (a) minimum (of) 50 ethnicities, over 200 languages and dialects. In a lot of ways, it wasn't necessarily set up for success.”

Samuelu also pointed out that the term AAPI is relatively new, but the debate isn’t. “AAPI as a racial category is younger than my parents. ... I think it's a great case study in the construction of race. By the time I was introduced to AAPI, it had already been disaggregated as a category. From the onset ... there were elders and ancestors and Pacific Islanders who really fought the aggregation, foreseeing what would happen. … The intent of AAPI is inclusion, (but) the impact, the long-term impact has been erasure.”

The intent of AAPI is inclusion, (but) the impact, the long-term impact has been erasure.

Tavae Samuelu

It's not just older Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPIs) who have called to separate NHPIs from Asian Americans. “I do hear complaints from young people — calls from young people saying like, ‘This does not represent me. I don't see myself in this.’" Samuelu said. "And so, I think from a Pacific Islander perspective, we're a highly relational people.

"I think there's also the visceral reaction to AAPI is the way that feels like it's a misnaming of our relationship to each other, of the realities that we face, and that race also often is a shorthand for naming relationship to power, relationship to whiteness, relationship to anti-Blackness. And so, there's a lot of ways that AAPI doesn't really contend with that or get at that nuance, and so, I think that's what comes up as young people are talking about that.”

There are now an estimated 1.6 million Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the U.S., but some are concerned they are overshadowed by the larger Asian and Asian American populations when it comes to much-needed vital health, financial and community support. “Resources and power are still distributed through AAPI,” Samuelu said. “I also see the ways that the category has not necessarily evolved as quickly as the population it seeks to capture, that even when it was created some 30 (or) 40 some odd years ago, there wasn't this critical mass of folks that there are now."

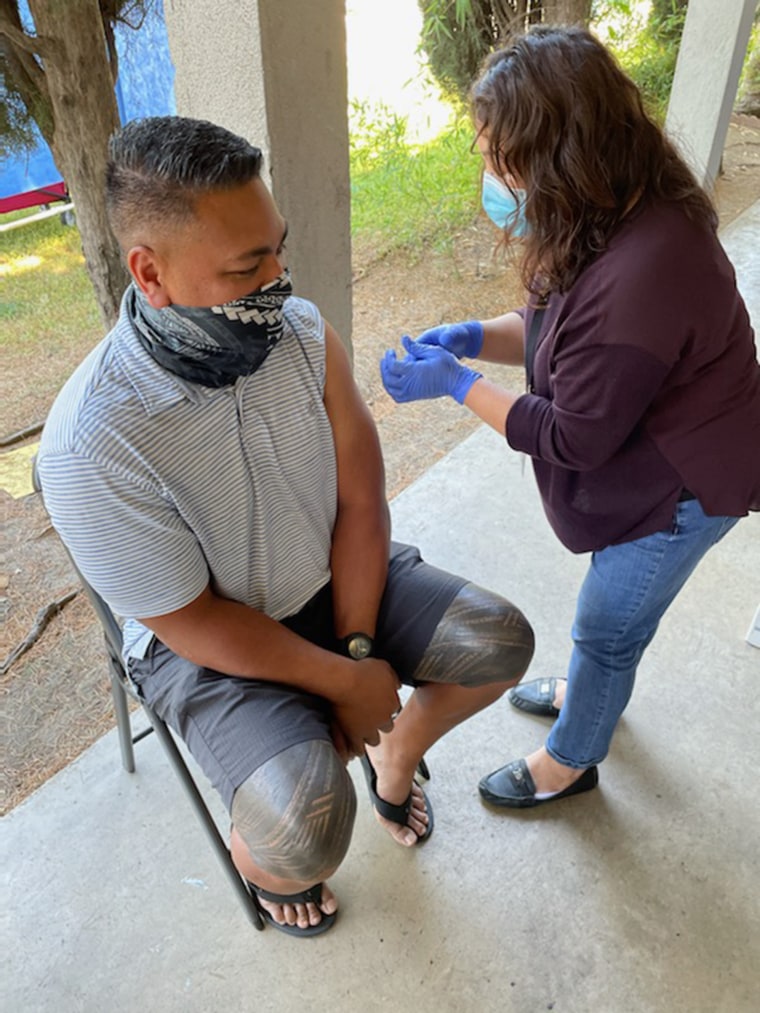

Samuelu highlighted that data disaggregation in particular was crucial in the last year. "The call for data equity for myself and for many other Pacific Islander communities ... the disaggregation of data was also how we saw the devastating impact of COVID on Pacific Islanders. Today, I want to say roughly 20 states of all 50, only 20 of them disaggregate data on NHPIs. Sixteen of those 20 show that NHPIs have the highest COVID infection rates."

With NHPI data, EPIC was able to create a response team, dispatching community health workers to help distribute COVID-19 vaccines to local Pacific Islander communities in California. It's just one example of EPIC's mission to empower Pacific Islanders. "The impact was not just to our physical health and health care access, but it was also around housing, around food insecurity," Samuelu said. "And so our work has also pivoted to be inclusive of those things, that EPIC wasn't necessarily designed to be a direct service organization, but we're answering the call right now and that while we're doing that, we are simultaneously holding on to our advocacy research and leadership development work."

Samuelu said the push to separate NHPIs specifically from AAPI is not unique to the demographic. “Also, I want to acknowledge that Pacific Islanders are not the only population that is often at a disservice under AAPI, that South Asians and Southeast Asians have also named the ways that they've had to grapple with AAPI as an umbrella.”

As Pacific Islanders continue to fight for more recognition and raise awareness of their individual needs, Samuelu is hopeful for the future. “There is definitely a reckoning to happen, definitely a conversation for Pacific Islanders to decide how we want to be stated and also, many of the conversations I have with Asian American comrades, organizations, co-conspirators, sometimes is a calling in, of holding folks accountable to AAPI.

“It's really like, 'How do we have a multitude of representations and understanding so that nothing becomes the single story of our community?'”