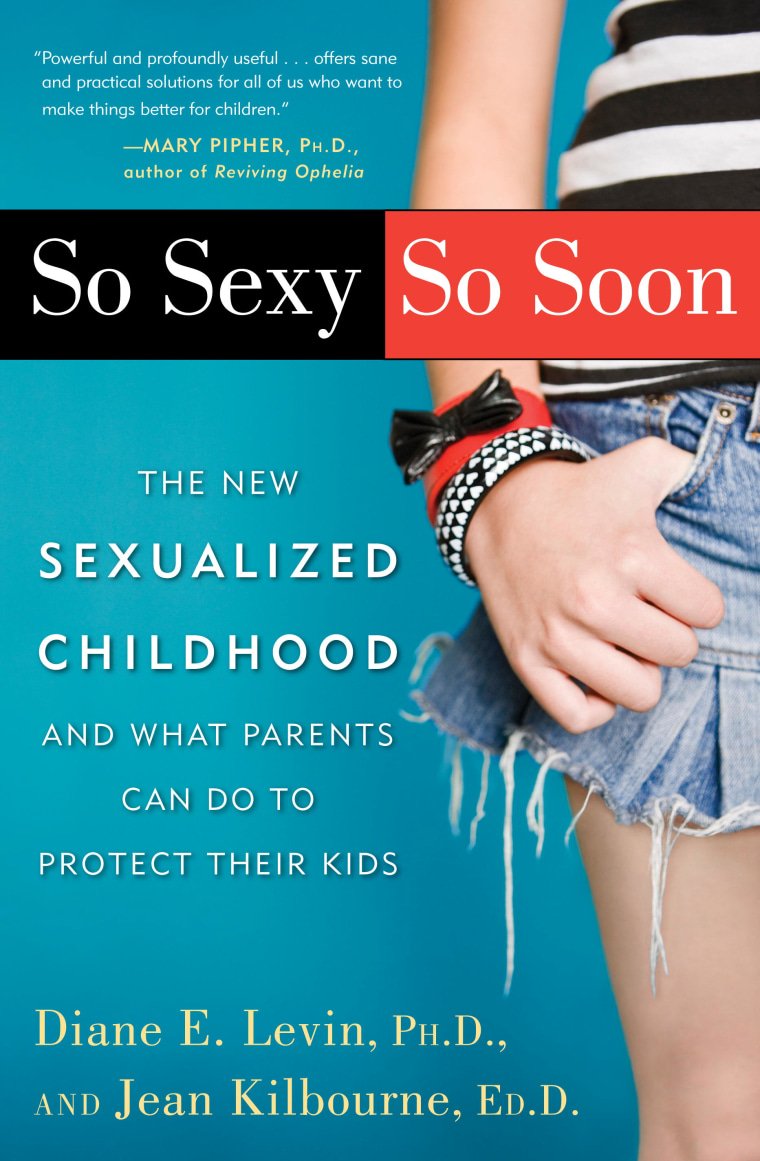

In their new book “So Sexy So Soon” authors Diane Levin and Jean Kilbourne write about the trend of children becoming sexualized at a young age due to media images and marketing campaigns that encourage youth to be “sexy,” and they offer advice on how parents can protect their kids. An excerpt.

Chapter one: Never too young to be sexy

It has never been easy being a parent. But today, it has gotten even more difficult. A 2002 survey by an organization called Public Agenda found that 76 percent of parents felt it was a lot harder to raise children today than when they were growing up, and 47 percent reported that their biggest challenge was trying to protect their children from negative societal influences, including disturbing and confusing images, violence, and age-inappropriate messages appearing in the media. How would you have answered this survey? Are you, too, having a hard time trying to protect your children from negative influences? Are you finding it difficult to set and enforce limits on the media that your children are exposed to — to determine how much, when, and what? As parents, you are often told that it’s your job to “just say no” to all of the inappropriate content out there, and that this will solve the problem. But just saying no won’t solve the problem, and anyway, you can’t say no to everything! Instead, we simply have to deal with the popular culture in our children’s lives, often at the most unexpected times, in unforeseen ways, and whether we want to or not. This book is designed to help you do just that. And in order to be able to do so, the first order of business is to examine and recognize when and how the new sexualized childhood is influencing children from a young age.

Several recent books and news and research reports have expressed concern about today’s sexual attitudes and behavior of many adolescents, and increasingly even tweens (eight- to twelve-year-olds). These accounts often make it seem as if the behavior in question suddenly appears out of a vacuum when children enter high school (or middle school). Rarely do we hear about what was happening in the early years that paved the way for what is happening with teens.

There is a lot going on in children’s lives around issues of sexuality and sexiness that is important for the caring adults in their lives to recognize. The following stories from parents and teachers make it very clear that if we are to understand and deal with the sexualization of childhood, we must begin our efforts with very young children.

Crying in the bathtub

Jennifer reported that one evening not long ago, her seven-year-old daughter Hannah began crying in the bathtub. Alarmed, Jennifer asked what was wrong. Hannah responded, “I’m fat! I’m fat! I want to be pretty like Isabelle — sexy like her! Then Judd would like me too!” Jennifer knew Isabelle, a very thin, very popular girl in Hannah’s class who wore “stylish” clothes that Jennifer thought were inappropriate for a seven-year-old. Jennifer put her hand on Hannah’s shoulder and said she liked Hannah’s body — it was a wonderful body for a seven-year-old and she certainly didn’t need to lose weight. But Hannah continued to cry and to say that she wanted to go on a diet. Jennifer felt uncertain about what to say or do next. In her view, Hannah had a normal body for a seven-year-old girl. Jennifer thought it must be abnormal for such a young child to be thinking about diets, let alone wanting boys to like her for being “pretty” and “sexy.” But, normal or not, Jennifer saw that Hannah was truly concerned and distressed, and she wanted to do something to help.

As Jennifer strove to understand Hannah’s outburst, she was tempted to put a lot of the blame on Hannah’s friends, who were becoming increasingly influential and important to her. Recently, Hannah had come home from a playdate talking about having had a fashion show with her friend’s Bratz dolls. Jennifer was concerned that when Hannah and her friends played together they often acted out going on “dates” and having weddings with their Barbie dolls, but she was truly horrified by the time they spent at other houses with Bratz dolls — by their name, their anorexic-looking bodies, their overt sexuality and hookerlike wardrobe, as well as by the focus on shopping and appearance as the point of the play. When she voiced her reservations about Hannah’s having the dolls, Hannah said that everyone else had them and that she loved playing with them at other children’s houses. She and her friends liked dressing them up and having them go shopping and out on dates. Although Jennifer didn’t give in, she wasn’t sure what she would do when Hannah’s birthday arrived the following month. She was certain some other girls would give these dolls to Hannah as gifts. Even if Jennifer took them away, she knew Hannah would continue to play with them at her friends’ homes. Recently, Hannah had begun to nag about joining the Bratz website, an online community where kids can play and buy things for their Bratz dolls in cyberspace, along with other children who are logged on.

Deep down, however, Jennifer realized that what worried her most was where this interest in appearance, popularity, and sexiness would lead. If Hannah was dissatisfied with her body at the age of seven, she wondered how she might feel at thirteen. Jennifer had seen news stories about an increase in precocious sexual behavior among children and teens, and she knew that eating disorders were on the rise, even among little girls. Were Hannah’s tears about her body the first sign of such trouble for her? What was the relationship between concerns about body image and sexuality? And what did she mean by being “sexy” anyway? Knowing how high the stakes were, Jennifer felt almost desperate to find the right way to respond. But she was upset with herself for feeling unsure, even anxious, about knowing the right thing to say or do.

Professional wrestling girls

Nora, a highly experienced kindergarten teacher, told us about an incident with a child that left her scrambling to figure out how to respond. In his daily school journal, five-year-old James had made a drawing of what looked to Nora like a woman, with long hair and bright red lips as well as big wavy circles on her chest that looked like breasts. Next to the drawing he had written the letter W over and over again. Nora asked him to tell her about his picture. She was caught off guard when James explained that his drawing was of “a professional wrestling girl with big boobies.”

“At first I thought he was trying to be fresh, to be a wise guy, but I caught myself before I reacted too harshly,” Nora reported. “I took a deep breath and tried to think through how to respond. I decided to start with a question.” (This is almost always a good way to start when you’re not quite sure what to say.) So Nora asked James what he knew about “wrestling girls.” He matter-of-factly replied with his eyes open wide, “I saw her on TV last night with my [big] brother, Brett. He was babysitting! He let me stay up late and watch with him! It’s a secret!” She was glad she had asked him the initial question about what he knew about wrestling girls, because his response helped her begin to get a handle on what was going on for James.

Nora recalled that it was the look on James’s face when he answered her, of both bravado and worry at the same time, that left her confused and concerned. She knew that James’s parents were quite clear about limiting the amount and kind of media in his life. She knew how much James looked up to fourteen-year-old Brett and admired everything he did. She was pretty sure that James’s parents would be distressed if they knew about Brett and James’s secret! She was also pretty sure that if James shared the secret with her, he was asking for something, but what exactly was it?

Rather than try to work it all out with James at that moment, Nora decided to buy some time to think about what to do. So she said to James, “It sounds like you saw things you hadn’t seen before ... things that were not really for kindergartners. I’m glad you told me about your secret.” James smiled and put his journal away.

After the event was over, there was a lot for Nora to consider. Why did James decide to disclose the secret to her and do it through his daily journal? Why did he choose to focus on the breasts? Did he know that focusing on them could be seen as provocative to his teacher or have sexual connotations? After all, what signifies sex to an adult might mean something quite different to a five-year-old. Was James trying to use his drawing to brag and feel more grown up about his having seen this grown-up program? Or could he have made his drawing because he needed someone to talk to about it when he knew he couldn’t reveal it to his parents because it was a secret? Was he testing Nora to see if she would get upset or angry, or looking to her to help him sort the experience out?

Nora began to think about the issue more broadly than just about James. If James drew his picture of the “professional wrestling girl” as a way of talking to an adult about something disturbing he saw on the screen, as Nora now thought he did, do other children also need such opportunities to process the graphic content they are seeing in media and popular culture? Well, then, whom are they talking to? How often do children end up seeing things their parents don’t want them to see and then learn not to talk to adults about it? And when they do experience the forbidden fruit, what does it teach them about honesty and deceit and about the nature of their relationship with the important adults in their lives?

Finally, Nora started to feel better about how she had responded to James and realized she had learned an important lesson for her future teaching: Whether they’re scared or want to feel grown-up and impress others with what they’ve seen, this is the kind of conversation with an adult that children often need in order to help them deal with the sex and violence they see. Furthermore, such conversations might also be used to teach children alternative lessons to what they’re learning from the screen.

But Nora didn’t leave it there. She began to think about what should happen beyond the classroom. What should the role of schools be in helping children (and their parents) deal with the sexualized media culture? How was this experience with James related to debates that were raging around the country about whether to teach sex education — and, if so, what kind and when? More particularly, did she have a responsibility to talk with James’s parents about the professional wrestling girl episode? If she did talk to them, would this upset James and make him feel he couldn’t trust teachers and other adults to help him deal with scary secrets next time? Or would speaking with the parents help them connect more positively with James so that it would be easier for him to use them next time, rather than his teacher, to talk about what he’d seen on TV?

Nora was aware of a 2006 Kaiser Family Foundation report that found that many children spend more time involved with media than on anything else but sleeping. So why wasn’t media education part of the school curriculum? Why didn’t schools see that they have a vital role to play in helping to influence the lessons that media are teaching children? Was the push to teach the “basics” for standardized tests that came from the federal government’s “No Child Left Behind” mandate crowding out content that children urgently needed to work on? If children didn’t have avenues to deal with their feelings about media content, what happened to these feelings? Did their involvement with the disturbing and confusing images and behaviors they saw distract them from giving their all to traditional schoolwork?

While there was not one right or easy answer to most of Nora’s questions, she realized that the increasing exposure of the children in her classroom to confusing sexual content was creating new challenges for her that she needed to take seriously. We need more teachers like Nora in today’s world!

‘What's a blow job?’

Meghan recounted with obvious distress that her seven-year-old daughter, Eva, had come home from school the day before and asked, “Mom, what’s a blow job?” Meghan’s first impulse was to tell Eva that it wasn’t something for children, it was for adults, and to terminate the conversation then and there. But something about the earnest expression on Eva’s face made Meghan pause. “Stay calm, stay calm!” she told herself. Then she asked, “Where did you hear about blow jobs?” Eva replied that she heard about it at school. Meghan followed with, “What did you hear about it?” Eva responded, “It’s sex.” Meghan couldn’t imagine where to go next with the conversation.

Meghan had always tried to protect Eva from exposure to violence and sex in the media. But ever since Eva had entered a large elementary school with many children who were not as protected as Eva, Meghan felt she was increasingly losing her ability to control this exposure. This new episode left Meghan feeling that things were really out of control. She had been aware, with some degree of ambivalence, that she might need to talk with Eva about issues such as oral sex during the adolescent or even the preadolescent years. She had heard news reports about incidents of oral sex in high schools. She had read that several boys at a private school near Boston were expelled because a girl had performed oral sex on all of them in the locker room. More recently, a friend had told her that two girls at a bar mitzvah had performed oral sex on the bar mitzvah boy in a bathroom. She certainly was disturbed by these incidents, but she was utterly appalled that the subject had come up with Eva at age seven!

Meghan and her husband had talked about how they wanted to be open and comfortable with Eva when talking about sex. But they had expected Eva’s first questions to be about where babies come from, not this. This was simply not what they had had in mind! Should Meghan actually describe oral sex? What could this possibly mean to a seven-year-old? And how would her explanation affect Eva’s understanding about sex and relationships between caring adults, both short and long term? Meghan also didn’t know what to think about the children who had used the term “blow job” in Eva’s presence. Where were they getting this language? What did they know?

You might think that Meghan’s experience is an aberration. Initially we thought so too. It certainly isn’t an everyday experience that parents have with their children. But when we shared this story with a group of parents at a workshop, a father excitedly (and seemingly with relief) raised his hand and said, “The same thing happened with my son. He’s eight and last week he came home from school asking, ‘What does it mean to “suck your d---”?’ I figured we were the only family dealing with this. That’s why we came to your talk tonight!”

Sexual harassment at age 5?

Jason got into trouble one day when his kindergarten classmate Ashley came home from school and reported to her parents that Jason had told her that he wanted to “have sex” with her. Ashley’s parents, very upset, told her she should never play with Jason again, that he was a bad boy. They then contacted the teacher and the principal and demanded a meeting with Jason’s parents. All of the adults involved were concerned about what might be going on in Jason’s home for him to come up with such a comment at the age of five. In some circumstances, such comments from young children can be an indication of sexual abuse. The principal, a firm believer in the school’s Zero Tolerance policy that said any child who committed an act of aggression or violence was subject to suspension, was considering a brief suspension to teach Jason that he should never say such a thing.

Fortunately for little Jason, the school psychologist met with him before this could happen. She told him that some people were worried about what he said to Ashley. She asked him if he would tell her what he said and what he had wanted to do to Ashley. Jason instantly burst into tears. He sobbed, “I wanted to kiss her. I like her. I like her.” This was the first time anyone had bothered to ask Jason what he meant by what he said, a potentially damaging error on the part of the adults. They were all using an adult lens for interpreting what he said about sex, not a child’s lens. Often when adults think “sex,” children have something very different on their minds.

An important question to ask in this situation is to what degree Jason’s comment grew out of his efforts to make sense of the messages about affection, sex, and relationships that he might be getting every day from popular culture. While it is hard to answer this question in hindsight, in these times it’s probably safe to assume that the popular culture could very well have played a significant role. Had it not been for the school psychologist, he might have been punished for doing something he’d learned and internalized from those messages. Jason, as much a victim of the sexualized popular culture as Ashley, was also victimized by the adults’ fear and misunderstanding.

We can only be grateful that the psychologist found a way to connect with Jason, to hear his point of view. We can hope that Jason got the kind of support he needed to regain his self-confidence and to learn how to express affection for his peers in appropriate ways. We also hope that Ashley got help working through the misguided and disturbing response she got to Jason’s words from the adults around her.

A highly publicized story about a first-grader in the Boston area did not have such a happy ending. A boy was suspended from school for a week when a girl in his class reported that he touched her skin inside the waistband of the back of her pants. The Zero Tolerance policy in his school left no room to take into account the understanding or possible needs of this seven-year-old child. Once again, here is a child paying a high price for the new sexualized childhood and adults’ reaction to it. And both stories illustrate a very disturbing trend — as adults get more and more uptight about how the sexualized environment is affecting children, they end up ascribing adult intent to behaviors that would have been interpreted as “children just being children” in the past.

Premature adolescent rebellion

The big topic of conversation for Tessa’s eighth birthday was the upcoming party — a sleepover with her three best friends and a magic show for entertainment. Tessa and her father had been learning magic tricks together and Tessa was excited about this new skill. Both parents were enthusiastic about the magic show too, since they had been afraid Tessa would want to show her birthday guests a DVD for entertainment. It was always a problem to choose an appropriate one. At the party, the magic show was a big hit, and Tessa taught her appreciative friends how to do the tricks. But later in the evening the bubble burst for the parents.

After ice cream and cake, the girls retired to Tessa’s bedroom to get ready for bed. About a half hour later Tessa’s mother, Kate, quietly went into the hallway to see how they were doing. Through the bedroom door, left slightly ajar, she overheard a conversation that took her breath away. The girls were talking about what Cassie, a girl in their class who was not at the party, had worn to school that day — a midriff shirt that exposed her belly button. Kendra said, “My mom says I can’t have one. I keep telling her it’s not fair.” MacKenzie said without hesitation that her mom let her choose the clothes she wanted and Kendra’s mom was really mean for not letting Kendra choose her clothes. Emily agreed. Tessa seemed not to be participating much. As Kate continued to eavesdrop, she learned that “the boys like Cassie.” They chase her on the playground, and one of the boys actually ran up to her and kissed her! Kate also learned that the boy is Cassie’s “boyfriend” now, and he likes her because she’s “sexy.”

The girls talked on and on — about how it wasn’t fair that Cassie got to wear whatever she wanted. Even MacKenzie and Emily, who had shirts that showed off their belly buttons, complained that they couldn’t wear them to school. Furthermore, the girls then discussed how they could get their parents to let them wear these shirts to school. MacKenzie and Emily gave Tessa and Kendra advice about how they could bypass their parents by getting their grandparents to buy them belly button shirts. All the girls agreed that grandparents often buy things that parents won’t buy.

MacKenzie boasted that she had seen a copy of the magazine CosmoGIRL! at her teenage cousin’s house. It showed really skinny models wearing really short belly button shirts that were “sooooo cool.” There was even an article on dieting. This led Tessa to pipe up, proudly announcing that she was on a diet and that she was going to be really skinny. The other girls said they were going to go on diets too. Kate wondered how Kendra, who was in fact somewhat overweight and had fallen strangely silent, felt about this discussion.

Kate was stricken. She was appalled that eight-year-olds were thinking and talking about such things. She thought that such topics — worrying about being sexy, skinny, and popular with boys and trying to figure out how to trick parents — didn’t emerge until early adolescence at twelve or thirteen. She wanted to barge into the bedroom and tell the girls that they were far too young to have such concerns. She wanted to tell them to go to sleep! But rationally Kate knew that even if she did march in to voice her concerns, the issues raised in the girls’ conversation would not go away. Rather, they would just stay underground as the girls continued to try to understand these issues beneath the radar of critical adults.

Many questions were spinning around in Kate’s head, none very comforting. First, she wondered about the girls’ envy of Cassie and their desire to be “sexy” and popular with boys, like her. Weren’t the girls a little young to be thinking about themselves and their peers in terms of sexiness bringing popularity? They were talking about one another and Cassie as if they were objects who would be judged entirely by their looks and whether or not their clothing was sexy. Second, Kate was concerned about the seemingly strong peer pressure in the group to look a certain way and to judge themselves and one another by their success in that narrow effort.

But Kate was most upset that the children were talking about adults, their parents, as if they were “the enemy,” opponents who prevented them from buying and wearing what they needed to be happy and successful. This seemed like adolescent behavior to her. Of course, one of the developmental tasks of adolescents is to separate from their parents and become more independent as friends and peers play increasingly important roles. Kate understood this in theory. But weren’t these children a bit young to be starting their adolescent rebellion? Was this a premature adolescent rebellion? Was this the age compression she had heard about, where issues that used to be of relevance to older children were moving down to younger and younger children?

Learning about sex from the Internet

Connie teaches health education to the fifth- and sixth-grade children in her school. By the time the children get to these grade levels, they are generally quite comfortable discussing personal topics with Connie and with one another. Still, she meets with the boys and girls separately a couple of times during the sex education course, because this helps them be more open to discussing uncomfortable issues related to sexuality. Several years ago, a comment from one of the boys in the boys-only session gave Connie reason to be concerned. She had been talking with the boys about the idea of sex occurring in a relationship as an expression of deep affection between the sexual partners, when a boy named Gabe jumped in and challenged her by saying, “Well, I think you don’t need to like the person. I saw sex on the Internet. My cousin showed me. They just do it ’cause it’s fun, they like it.” A couple of boys seemed surprised, but a few others said that they had seen it too and that Gabe was “right.”

On the one hand, Connie was upset that some of the boys had access to pornography on the Internet. On the other hand, she considered it a positive sign that Gabe had felt comfortable enough to raise the issue with her, and that other boys in the class seemed interested in the topic. Clearly it had been very much on their minds and they really wanted to talk about it. But how did this comment of Gabe’s affect one of the most basic lessons she had always tried to teach the children — that sex is a special part of a relationship between caring adults? Even though she was a veteran teacher and expert in this area, Connie was stumped for the right response to comments like Gabe’s.

In subsequent years, and because of the now ubiquitous access to the age-inappropriate content on the Internet that many kids are exposed to, Connie decided to change her approach to her first boys-only session. “Early on I ask them what they have seen about sex on TV, in movies, or on the Internet. Last week, every boy raised his hand when the issue of having seen ‘sex’ and pornography on the Internet came up. When I probed to find out more about what they saw, it was clear that two or three of them hadn’t seen real pornography, but I think all the others had! The times have changed very rapidly since Gabe first raised the issue of pornography on the Internet in my class, and the issue certainly adds a whole new dimension of complexity to the work that I do.” Connie’s realization that she had to bring the media and popular culture into her discussions about sex was an important breakthrough. As she began doing this, what Connie learned about how to lead such discussions (described in Chapter 6) can help us all become better able to talk with children about the sex they are exposed to in media and popular culture.

Meeting the challenge

Did any of these parents’ and teachers’ stories sound familiar? As you read, what kinds of reactions did you have? You might be asking, “What’s happening to the world? This would never have occurred when I was their age.” Do you wonder what might be going on with your own children that you don’t even know about regarding sexual issues? Are you thinking, “How is all this going to affect my children’s healthy sexual development as they are growing up? If children at five, six, and seven years old are doing things like this, what will be going on when they are tweens and adolescents?” Or perhaps you feel angry, not with the children who are struggling to understand sex and sexuality, but at the world that contributes so negatively to these struggles. Do you wonder how it got to be like this? Do you worry about what you can and should do?

Each of these stories has a lot to do with sex and sexuality. But they also have implications — that go far beyond sex — for children’s overall development, attitudes, and behavior. For example, we see the beginning of a premature adolescent rebellion as young girls try to figure out how to trick their parents into buying them sexy clothes so they will be popular with the boys. We see a clash of cultures between parents and the media as ten-year-old boys learn lessons about sex from the Internet that undermine the lessons about sex in the context of loving relationships that caring adults are trying to teach. We also see examples of the objectification of oneself and others as both girls and boys learn that how you look rather than who you are determines the value others place on you. Unfortunately, it’s not a very big leap from this kind of objectification to a range of unhealthy emotional consequences such as eating disorders and depression.

There have always been changes in society from one generation to the next. Parents have always noticed how their children’s world differs from the world of their own childhood. But what is happening now regarding sex and sexuality in the media and popular culture goes far beyond the changes that have occurred between other generations in the past. A revolution is taking place that we need to take seriously. It is a revolution that is harming our children and harming the wider community. We must understand this new world in order to help and protect our children. In order to do so, we need to have more information and more skills than our own parents needed. We all want our children to grow up capable of having healthy and caring adult relationships in which sex is a part. This is a more difficult task than it used to be, and we must all work together to find ways to help our children adapt to a rapidly changing world. There are no easy answers, but the first step is to learn about what is going on today.

As James Baldwin said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Excerpted from “So Sexy So Soon: The New Sexualized Childhood and What Parents Can Do to Protect Their Kids” by Diane E. Levin, Ph.D., and Jean Kilbourne, Ed.D. Copyright © 2008 by Diane E. Levin and Jean Kilbourne. Excerpted by permission of Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.