A centuries-old expression about the product of the vine assures us that “in wine there is truth.”

Budge Brown is putting all his chips on that promise.

In 2005 the California winemaker lost his wife of 48 years to breast cancer — a pernicious enemy that left him feeling helpless, heartsick and ultimately angry. In recent years, though, Brown has become a man on a mission to make wine with a mission: Raising money to jump-start breast cancer research that’s never been done before.

“I had to turn that anger into determination somehow,” said Brown, 76. “I just refuse to believe that in this day and age there’s no cure for cancer.”

Brown began waging his very personal battle against breast cancer by purchasing a wine label with a name that had the potential to turn some heads: Cleavage Creek.

“It was a little controversial to do that, maybe,” Brown recalled. “I decided it could be a good fit.”

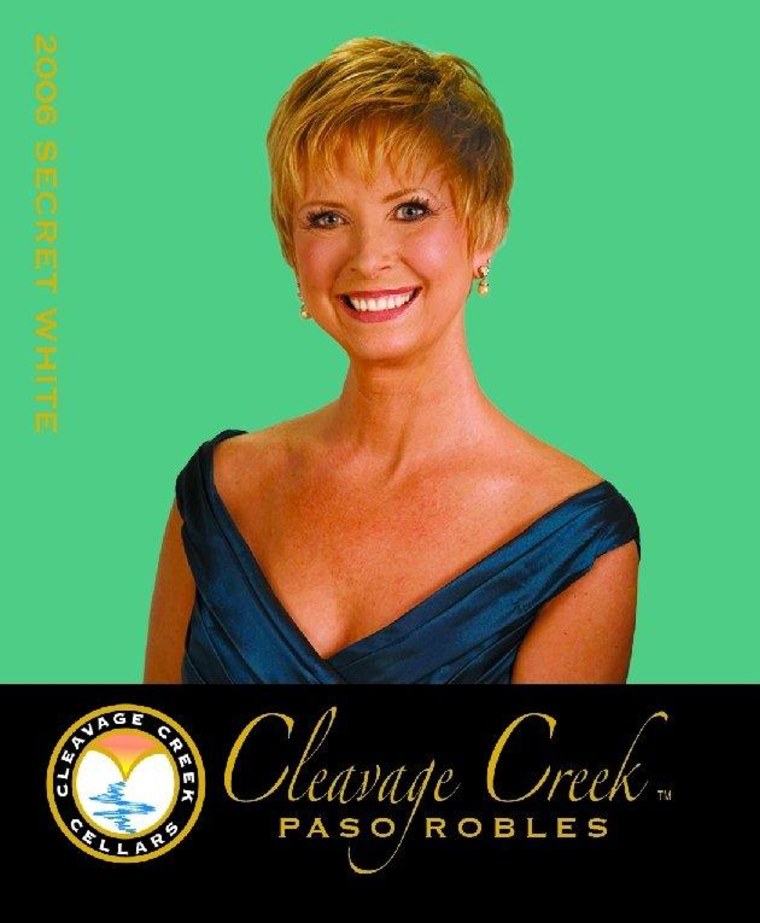

Today each Cleavage Creek wine bottle features a cheerfully tasteful image of a breast cancer survivor. The women’s stories are shared in detail on the Cleavage Creek Web site.

“Some people get a little huffy and say, ‘How dare you put a sick woman on your bottle?’ ” Brown said. “We say, ‘She’s not a sick woman, she’s a survivor.’ A lot of them are doing well.”

Ever since Cleavage Creek Cellars released its first eight varietals on Oct. 15, 2007, Brown has been donating at least 10 percent of his gross sales, along with funds of his own, to cancer research. To date, he has given away nearly $60,000 — $40,000 of which just went to Bastyr University for the launch of an Integrative Oncology Research Clinic in Kenmore, Wash.

In the world of philanthropic giving, $40,000 isn’t a massive amount — but what it’s making possible in this case could turn out to be huge, said Dr. Leanna Standish of Bastyr, an institution that has specialized in naturopathic medicine for more than 30 years.

Standish said she could have opened the clinic without Brown’s donation, mainly because insurance companies have been required to cover naturopathic treatments in Washington state since the mid-1990s. Bastyr has no shortage of insured cancer patients who are seeking alternative and complementary forms of care.

Still, Standish has had lingering questions about alternative cancer treatments for years. And that’s where Brown’s donation comes in. It will pay for the initial phases of a controlled outcomes study examining the disease-free survival rates and quality of life in breast cancer patients.

One group of patients in the study will receive alternative treatments in addition to traditional Western treatments for breast cancer — typically some combination of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. Those women will be compared with another group of patients who receive traditional treatments only, without any alternative therapies.

“I’ve been doing integrative treatment for 19 years and I think it helps my patients, but I don’t really know,” Standish said. “When we get a chance to do a study with actual clinical outcomes, if we find out it doesn’t make a difference — or if we find out it hurts people — then I’m going to stop practicing medicine.”

A new kind of research

Bastyr University is teaming up with the respected Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle to conduct the study, which has the goal of following breast cancer patients for five years to see how they fare with their different treatment approaches.

“We completely respect surgery and radiation, and we’re very careful about not giving patients anything that would counteract the benefits of chemotherapy,” Standish said. “That’s the thing that scares oncology doctors. They’re afraid that their patients may be given herbs that would interact badly with their chemotherapy drugs. But we’re trained in that.”

Standish said Bastyr patients who participate in the study will receive traditional Chinese approaches to cancer treatment, such as acupuncture once a week and an herbal formula made up of Chinese herbs. They’ll also be given naturopathic treatments such as the use of acupuncture to ease nausea and vomiting, application of seaweed from Puget Sound to heal radiation burns, doses of enzymes to help their digestive systems during chemotherapy, and doses of the amino acid glutamine.

Robyn Andersen, a researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center who is working on the study with Standish, said it’s important to examine such a wide swath of different treatments in combination.

“A lot of the research we do has focused on individual activities — as in, does this kind of mushroom help? Does this chemo regimen help?” Andersen explained. “But most patients wind up getting a combination of things. They don’t normally try just one herb or one recommendation for change in diet ...

“Even just knowing that the efforts to reduce side effects such as nausea are effective would be very helpful for us to know in terms of helping patients.”

Andersen and Standish both dream of seeing their study become a full-fledged randomized control trial that is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). For the time being, though, they will get started and do as much as they can with the help of Brown’s donation.

Dr. Jeffrey White, director of the NIH’s Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine, said their planned approach to cancer research is unique.

“I’m not aware of other studies like this,” White said. “It definitely would be good to follow patients for that long.”

White highlighted the reason for a lack of comprehensive research in this area.

“There’s not a lot of communication between the naturopathic world and conventional medical world on the research side,” he said.

In short, many oncologists fear that alternative treatments will hurt their cancer patients, White said. He mentioned a 2002 study involving a practitioner of alternative therapies who had spent years of his career giving breast cancer patients megadoses of vitamins and minerals. The practitioner was convinced that the strong vitamin and mineral boosts were helping his patients.

“But in fact the analysis showed there was decreased survival in those who received the vitamin supplements,” White said. “So there is the potential for harm ... You just never know until the data is in.”

That, both Standish and Andersen say, is why they’re so eager for concrete data.

“Leanna [Standish] has spent a lot of her life on this, but she only wants to keep doing it if it’s really working,” Andersen said. “That’s part of why I’m so excited to be working with her. A lot of times you’re working with someone who’s pretty convinced of what the results of the research will be, but she’s completely open ...

“I’m just hoping we can provide data that can help improve the quality of this conversation.”

‘Trying to make a difference’

For his part, Brown still has a lot of regrets and pent-up frustration about what happened to his wife, Arlene Brown. As soon as she learned she had breast cancer in 1998, Arlene opted for surgery to have the cancer removed.

“After that, we thought we were home free,” Brown said. “In fact, we were celebrating the end of five years cancer-free, and she had a massage. A rib broke.”

Subsequent checkups revealed that cancer had spread to Arlene’s brain, liver and bones.

“She had cancer all over,” Brown said. “We had a two-year battle to bring it under control, and we didn’t make it ...

“If you ask me, my wife died for no damn good reason.”

These days, Brown spends time in the garden he created in his wife’s memory. Overlooking a lake on the property of his Napa vineyard, the garden contains Arlene’s favorite flowers, including more than 20,000 daffodils, 10,000 iris and a host of California poppies, tulips, roses and wildflowers.

“I want people to visit Cleavage Creek and celebrate life and health,” Brown said. “There’s no better way to do that than with a fine wine and the company of those who are a part of the fight.”

Brown said he plans to keep directing money toward cancer research that otherwise might not be pursued.

“I’m just a farm boy,” Brown said. “I don’t pretend to be a doctor or an M.D., and I don’t pretend to know what the hell I’m doing. I’m just out there mucking around, trying to make a difference.

“I hope we can show that there might be another way.”

To buy Cleavage Creek wine, visit .

To read the stories of the breast cancer survivors who appear on the Cleavage Creek bottle labels, .

To learn more about Bastyr University’s new Integrative Oncology Research Clinic in Kenmore, Wash., call (425) 602-3311 or .

If you are a cancer patient who is interested in participating in clinical trials involving complementary and alternative medicine, visit .