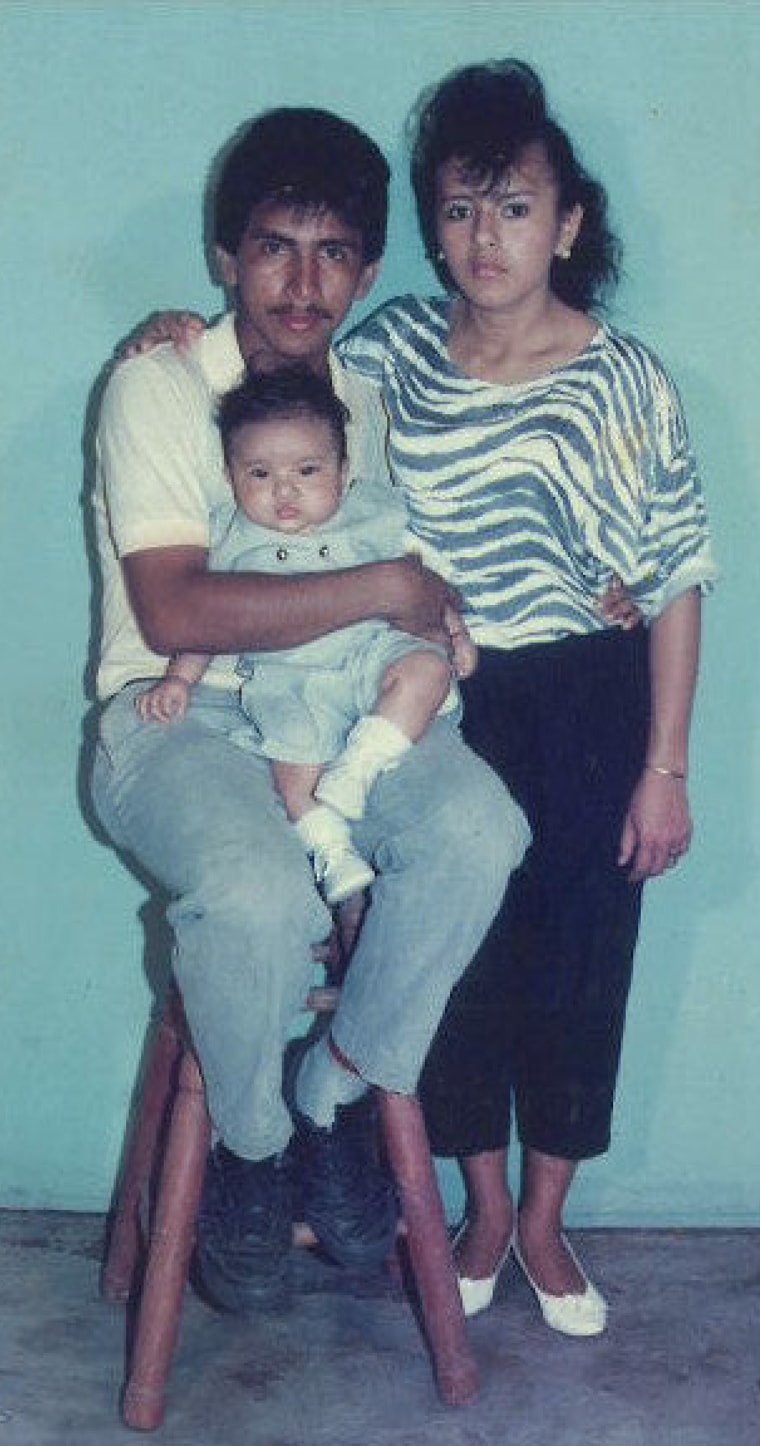

Since November 2019, every Wednesday I’ve woken up early to meet with Caro, my therapist. When we first met I had only written a few thousand words of "Solito," my memoir about my nine-week migration from El Salvador to the United States when I was 9 years old. My grandpa accompanied me for two of those weeks, then said goodbye at the Guatemala-Mexico border and left me in the care of the coyote, Don Dago, my family had paid. The same 50-year-old man had smuggled my mom into the United States four years prior in 1995. Relative to other immigration stories my parents and grandparents had heard about, Mom’s trip was relatively safe, quick and easy, and so my family trusted Don Dago. My trip turned out to be the complete opposite. The coyote lied and abandoned a group of six of us (two children and four adults) when we boarded a small motorized skiff to cross into Mexico via the Pacific Ocean. Seven weeks, one boat ride, several bus rides, many long walks in the desert and almost 3,000 miles later, I was reunited with my parents on June 11, 1999.

From that hot summer day that I was picked up in Tucson, Arizona, until my first meeting with Caro in her first-floor office in New York City's West Village, I had not seriously looked back at the events of those nine weeks. I say seriously because I published my first book of poems, "Unaccompanied," in 2017, where I began to depict some of my journey from El Salvador to the United States. In hindsight, those poetic snapshots of names, images and sounds were as much as my brain and body could handle at that time. For example, in "Unaccompanied," Chino (one of the strangers who became like family and took care of me during my journey) makes one single appearance. Patricia, Carla, Marcelo, Chele and Marta (the other strangers, some of whom also became family) never appear. I couldn’t speak their names, let alone allow my brain to look at their faces, remember their actions, feel their full human presence in my life. Even small details that I wrote in my poetry would end up triggering me as I revised the poems. When I felt triggered, my body wanted to feel something, and the only ways I learned to cope was via exhaustive workouts, sex, drugs and alcohol. As those close to me know, from the time I was a teenager and had my first drink, I was not the best person to be around.

In seventh grade, and days after my parents’ divorce, I threw a water bottle at a teacher, and so my school mandated counseling. For me, channeling my anger outwards became a coping mechanism. Perhaps because of this anger, I became a good enough soccer player to be offered a full-tuition scholarship at one of the most expensive high schools in the country. Weeks into my private school education, I threw a desk at my math teacher. I felt isolated, othered and misunderstood because I was one of only seven Latinx students in the entire school. Instead of expelling me, the principal (with the backing of my soccer coach) made me meet weekly with the school therapist. In college, I attended mandatory therapy sessions after my driver’s license was suspended for driving more than double the speed limit on a freeway. After that incident, poetry substituted soccer as my anger’s outlet and has continued to play a bigger role in my life. In graduate school and subsequent post-doc fellowships, health insurance was provided, and I voluntarily received mental care. Throughout my 20s, my immigrant journey haunted me and followed me like a shadow. But after publishing my first book of poems at 27, and receiving fellowships and awards for my “depiction of the immigrant experience,” I sincerely thought that I was healed. Writing and therapy provided a false sense of calm, so I stopped going to therapy and convinced myself I no longer needed it. Deep inside me, those nine weeks were still brewing, creeping up and wreaking havoc when I least expected.

From August 2018 to June 2019, I was granted a Radcliffe Advanced Studies Fellowship at Harvard University in order to complete my second book of poems about the “Central American refugee crisis.” My research revolved around reading every article and cataloguing every picture of Central American refugees that appeared in The New York Times from April 2017 to April 2018. Harvard provided monthly paychecks, housing, an office, health insurance and paid undergrads to help me conduct my research. Just weeks before moving to Cambridge, Massachusetts, the U.S. government deemed me worthy enough to qualify for the EB-1 “Einstein Visa.” After nineteen years of being mostly undocumented (for the last few years of those nineteen, I held “Temporary Protected Status,” or TPS, which allowed me to travel freely within the United States, but didn’t allow me to vote or travel internationally), I was finally completely “legal.” Every single privilege I’d asked for and fought for — housing, healthcare, immigration status, job security, access to free education — seemed to have been checked off my imaginary checklist and yet, I was still deeply unhappy.

The images of immigrants photographed on the worst days of their lives and articles about said experiences re-triggered me, placing my body somewhere, some hour, during my migration in 1999. At the same time, I was traveling all over former President Donald Trump’s America reading poems to strangers about being an immigrant and crossing the border. Even though at these readings I told people that I was doing the “healing work,” in reality, after these readings, alone with my trauma in empty hotel rooms, I went back to my coping mechanisms. And when I wasn’t traveling to readings, I was spending my Harvard money getting drunk in Cambridge. Midway through March 2019, after a binge triggered by the countless images I’d looked at of Central American child migrants, I abandoned my research project and decided I needed to tell my own story.

I was angry that non-immigrant writers, reporters, filmmakers and artists were telling and profiting from our immigration stories. So I decided I was going to seriously look at the days between April 4, 1999 and June 11, 1999 — the full length of my journey to be reunited with my parents. I had no clue how to start, but I knew the date when to begin. I looked at the weather on those dates. The temperature. Traced my bus rides on Google Earth. Flashbacks poured in like they never had before. I was at the gym every single morning. Began training for a marathon. I couldn’t sleep. My body was constantly in pain. I drank too much. Sought out drugs and sex — the same coping mechanisms, but this time, they increased in frequency and intensity. I mention this trajectory to illustrate how long I’ve struggled with something that, at times, not even mental health professionals could help me with. I wasn’t ready and didn’t want to face the everyday anguish and fear I experienced as a 9-year-old in foreign countries at the care of complete strangers. I truly believed no one could ever understand, that I was alone in my suffering, and that this internal and quiet anguish I kept hidden in public was as good as it was ever going to get.

I wasn’t ready and didn’t want to face the everyday anguish and fear I experienced as a 9-year-old in foreign countries at the care of complete strangers. I truly believed no one could ever understand.

It’s important I mention that out of all therapists before Caro, only one has been Latinx and none were immigrants themselves. I met my Latin American and immigrant therapist, Caro, by chance. In June 2019, I moved back to New York City after nine months at Harvard. One day in July 2019, on a Monday at 1 p.m., I was sitting in a Greenwich Village restaurant about to order my third martini, when across the bar a couple celebrating their anniversary started to talk to me. Because I had my laptop out, they asked what I was writing about. I answered. By the end of our conversation, one of them handed me her business card and told me to email her because she knew exactly who I needed to talk to. I carried that card in my wallet for weeks. After I almost missed a reading in upstate New York because I’d stayed up until 5 a.m. binge-drinking, something else clicked: I couldn’t face my immigrant journey alone. I needed to go back to therapy.

I sent an email. Kathy (the woman from the bar) turned out to be Caro’s professor and mentor. Caro and I started our weekly meetings on the day of the first winter snow in late 2019. By early March 2020, Caro and I had made considerable progress: I was finally ready to go deeper into my unaccompanied crossing experience at 9 years old. But not before I crashed and burned my personal life — real distractions that I created for myself so I wouldn’t dive deep into my life as a 9-year-old boy. As Caro likes to put it, I wasn’t aware of what version of me was “driving the car” that is my body. An angry driver was at the wheel and speeding into a brick wall. Slowly, I began to understand all of my drivers (versions of myself at different times of my life). Of course, facing scenes that I hadn’t thought about since they’d happened began re-traumatizing me before I was able to heal from them. This is where my now-wife enters the picture. Joey and I met in March 2020 — yes, really, four days before New York City officially shutdown. Caro tells me I have a knack for attaching myself to the right people at the right time. A survival tactic. This seemed to be true with Joey — a certified Reiki practitioner, yogi and woman years ahead in her own healing journey: an example of what a healthier life could look like.

When we met, I’d tried reiki before and thought of it as a waste of time and money. For those familiar with acupuncture, reiki employs a similar principle: its intention is to encourage the physical and emotional healing of our selves via movement of the energy stored in our bodies. Sometimes these energies get stuck and we feel out of balance. Other times, trauma or pain we’ve been carrying around leaves us feeling drained. In reiki, gentle touch (or sometimes just the movement of the practitioner’s hands over our bodies) is what guides our physical and emotional selves towards balance.

"Let me try,” Joey said one day, about a week into us dating. In my love life, for a long time, I’d been stuck. Because of her openness, I trusted Joey like I’d never trusted anyone, and allowed her into parts of me I’d never before revealed. In my writing life, I was also stuck. In the book that later became "Solito," I’d written less than 25,000 words. My body ached. I was drinking heavily. The city was shutdown. I was stuck inside my 500-square-foot Harlem apartment, and my body was thrown back to when I was 9 years old, locked inside a small “apartment” in Guadalajara alongside six strangers. During my first reiki session with Joey, images came rushing out. Immediately after our session, I asked for a pen and paper and didn’t stop writing until I’d recorded all the details of what would become the “jail scene” in "Solito." From that date onward, reiki and therapy became tools I used to revisit my trauma, but in conjunction with Joey’s love and care. In her eyes, I felt completely seen, human, and didn’t feel an ounce of judgment. The combination of all of these factors allowed me to begin to truly face the trauma that was weighing me down.

At one point, a change of scenery was also necessary. Joey and I moved from Harlem to Tucson, Arizona: a literal and physical facing of the landscape that had caused me so much suffering. Reiki and therapy continued to ground me and help me write the trauma out of my soul. I want readers to understand how difficult it has been to write "Solito." It has taken two very special individuals who believe in healing and who have enough energy and the capacity to help me along the process. One is a brilliant professional who is paid for her labor. The other is someone who I consider a goddess, my best friend, my wife. And they are not the only ones who have helped: friends have encouraged my healing journey as well, and knew when to check in. I’m also fully aware that having the access, the money and time for therapy and reiki is a huge privilege. My job has become my own healing and that is a rare thing. I feel very fortunate to heal in a public way, in the hopes that my own journey will inspire others to face their traumas with the aid of professionals and loved ones who can hold our ugly cries, our anger, our resentment, our fear, our shame, our aching muscles. There is hope. Healing and change is possible.