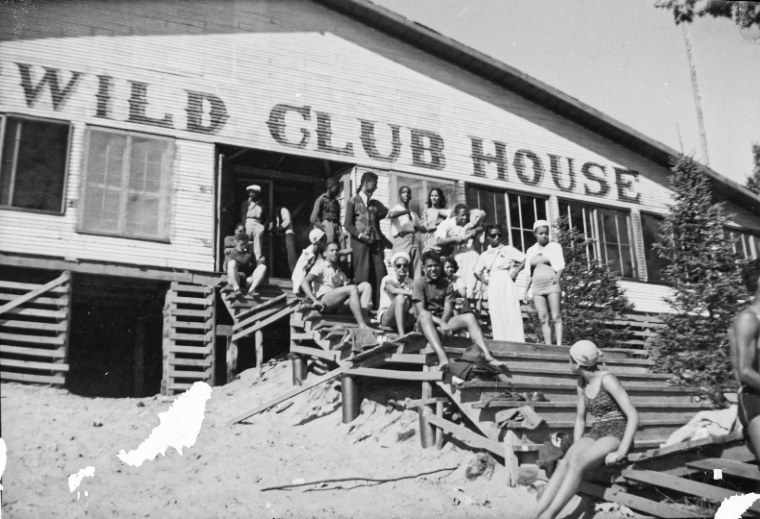

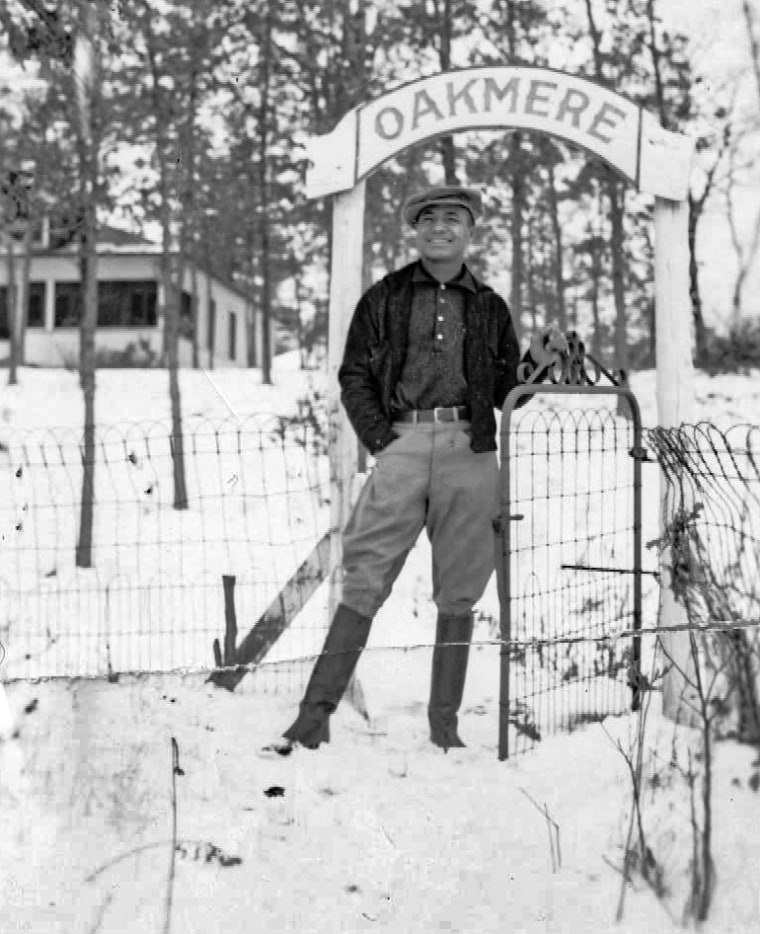

In 1912, prominent members of the Black community began vacationing in Idlewild, a thriving beach town in the forests of Northern Michigan. W.E.B. Du Bois, Madam C. J. Walker and other intellectuals and political figures came to this area, known as Black Eden, where Black families could relax and own property.

They found a safe haven in the Jim Crow era that denied them rights and equality.

“This was a place of refuge and relaxation,” said Susan Matous, who lives in the resort town year-round, in an interview with NBC News correspondent Meagan Fitzgerald.

Matous and partner Blair Evans spoke to NBC News about the cultural impact of Black Eden and their efforts to bring people back to the area.

“A lot of people appreciated coming to Idlewild in one sense, because you escaped from the oppression of being Black, but in another sense, because you can be authentically Black with other Black folks and talk about Black issues,” Evans explained.

He added that being in the community could change their “entire agenda from suffering through being Black to enjoying being Black.”

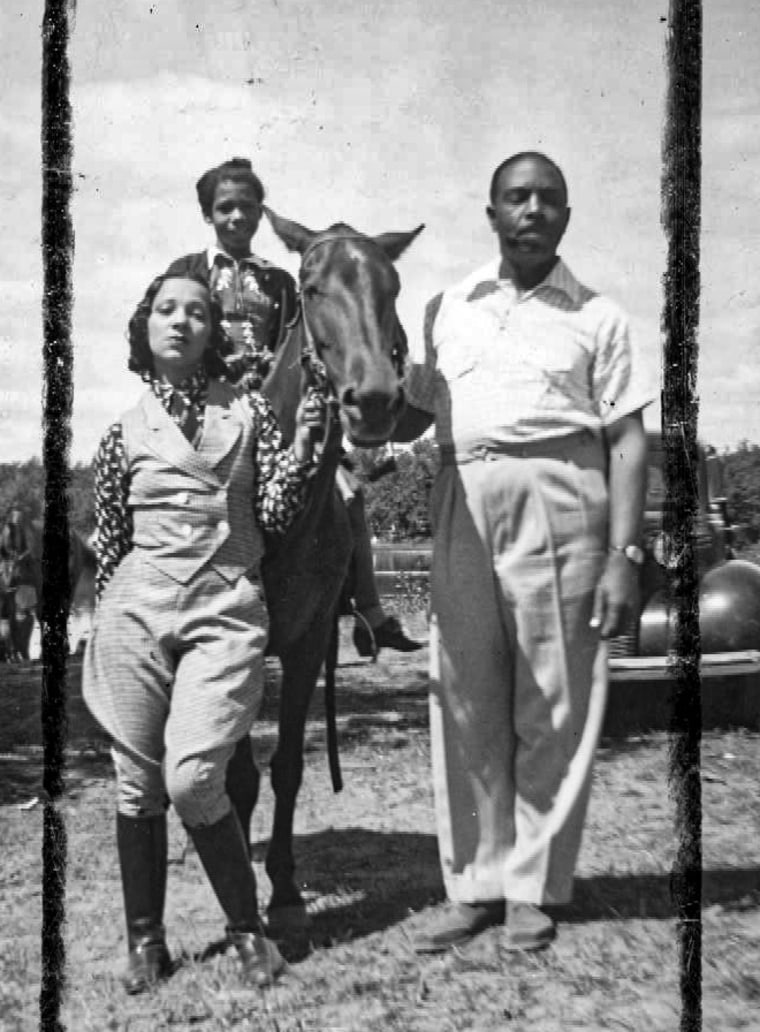

In the vacation spot, Black people were able to truly feel like citizens by owning real estate. Free from segregation and the horrors of being a Black person in America, they could swim, ride horses and be entertained without facing racism and bigotry.

But after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed, Black Eden’s popularity declined.

Marilyn Atkins, a resident with familial ties to Idlewild, told NBC News that “integration did a lot of damage” to the area.

She continued, “And my mother used to say that when integration came, Black people deserted Idlewild because then other places opened up and we could go anyplace.” Atkins recalled her mother getting upset remembering people leaving the community.

When she was just 9 years old, Atkins built a cottage with her father in Idlewild and said she traveled to the vacation home every summer.

Now, she has passed on that tradition to her daughter and grandson.

Atkins’ granddaughter, Elizabeth, is a third-generation Idlewilder who said the community gives her “a tremendous source of pride and it anchors us in our history and culture.” She feels an embrace of joy and freedom when she is in the beach town.

Despite Atkins and others pushing to rebuild Idlewild, there aren’t as many homeowners and tourists as there used to be in the historic vacation spot.

However, in the last few years, Evans and Matous and other members of the community have been encouraging Black families to buy homes and establish roots in the town.

The couple, who run a travel campaign called Experience Idlewild, have been hosting year-round events to increase tourism.

“There’s really been a rediscovery of Idlewild by a lot of younger folks,” Evans shared. “And so some younger folks are thinking about what would it mean to reinvent that for the next few generations.”

Some students have also been helping restore the Flamingo Club, a place where some of the biggest names in entertainment would stop by and perform.

Matous praised the Black ancestors who built Black Eden as “entrepreneurs” and “founders.”

“They laid the ground for us and now it’s time for us to take the baton to help carry this on,” she said.