From 2019 to 2020, hate crimes against Asian Americans increased by 150% in major cities like New York and Los Angeles, a study by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino, concluded. The nonprofit reporting forum Stop AAPI Hate revealed that they received 3,795 reports of hate incidents over the past year.

And those are just the statistics; accounts of the events themselves are even more chilling. On March 31, a man who was on lifetime parole for fatally stabbing his mother in 2002 was arrested on two charges of assault in the second degree after repeatedly stomping on and kicking a 65-year-old Filipino American woman in New York City in broad daylight. And a recent New York Times report lists more than 110 incidents in which anti-Asian sentiments are explicitly invoked — from Asians being spat on for causing the "kung flu" to a couple being told to go back to their country at gunpoint. While the pandemic has revealed the ugly underbelly of anti-Asian racism and discrimination in the United States, historians and experts emphasize that this is not new.

Dr. Jennifer Ho, who serves as the director for the Center of Humanities and the Arts and a professor of ethnic studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, isn't surprised by the current trend.

“Anytime the U.S. body politic seems to be under threat and that threat is coming from an Asian nation or Asian people, then very predictably, the United States goes into yellow peril mode and scapegoats Asians,” Ho, a critical race scholar, told TODAY by phone. “The biggest (examples) are around war. The Japanese American incarceration is the prime example.”

From the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States, to the internment of roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans and people of Japanese ancestry after the attack on Pearl Harbor during World War II to Trump's ban on foreign nationals from predominantly Muslim countries, the law has defined Asian Americans as forever foreigners, explained Ho. The target is always shifting, rendering certain populations more vulnerable to violence than others at different points in time — but the rationale behind the violence remains the same.

“After 9/11, we had over 300 calls about violence in November,” said Stanley Mark, senior staff attorney at the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund. “In New Jersey, there were quite a few bricks being thrown through the windows of South Asians and Sikhs, particularly people who wore turbans. The Sikh community was targeted.”

Since 1974, the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund has been fighting to protect and promote the civil rights of Asian Americans. With over 20 years of experience, Mark reiterates that people should look at these violent incidents as “a pattern coming out of a historical context.” He said remedies to systemic racism must come from political leadership and reinvesting in community-based solutions.

What to do if you witness a hate incident

Imagine if someone approaches an Asian person near you and begins yelling racist slurs at them. Would you intervene? How could you do so safely?

Hollaback!, a nonprofit created to end harassment in all forms, offers online training sessions on how to exercise bystander intervention tactics in response to anti-Asian violence.

“Seventy-nine percent of people say it improved the situation when someone intervened to stop the harassment, and only 25% of people say someone helped them," Dax Valdes, a senior trainer at Hollaback!, said during a recent session. "That is the gap that we want to close...our mission is for you to leave this virtual training ready to safely intervene when you witness anti-Asian xenophobic harassment happening in public or online.”

The organization teaches the five Ds of bystander intervention:

Distract: The intent of creating a distraction is to de-escalate the situation and create an environment in which the harasser feels excluded and will hopefully recede into the distance.

Delegate: Delegation requires bringing in someone else to help, often someone in charge of the establishment, another bystander or an authority figure.

Document: Take a photo or video of the incident and be sure to note where you are located and the time of day the incident is occurring.

Delay: After it is over, someone should check in with the person experiencing the harassment and make an offer of how you can support them.

Direct: You have the option of addressing the assailant directly with a remark as simple as “Stop doing that!”

Though the form of intervention that comes to mind most often is “direct,” the risks are different for every individual. Those of marginalized identities may also be scared of becoming the target of harassment, especially when police become involved.

“People also ask, ‘Why don't you just call the police or 911?’” Valdes said. “What we would challenge you to think about is that many communities, including communities of color, the Black community, immigrant communities, may not always feel safer with the police in light of the history of harassment that the police themselves have. What we recommend is that you check in with the person who's experiencing the harassment and see what they want you to do.”

What to do if you’re a victim of harassment

In addition to educating potential bystanders, Hollaback! offers training geared toward people experiencing anti-Asian harassment themselves. It outlines three different strategies people can use to respond to harassment while it happens:

Trust your instincts. “Listen to what your gut is telling you and note your surroundings,” said Valdes. Is there an escape route nearby? Are you safe with people who can support you? While you’re preparing to react, it’s also important to check in with yourself. Could the intersections of your identities put you at increased risk of harm? Or, could your perception of the situation and anticipated intervention plan be influenced by any implicit biases?

Reclaim your space. In other words, decide whether you want to respond in the moment and how. You can tell the perpetrator exactly what they’re doing and what you want them to do next, which could mean saying something like, “This isn’t appropriate; please step away from me.” Setting a firm and clear boundary should be the upper limit of engagement — getting involved in a back-and-forth could lead to escalation. Beyond that, you can also solicit the help of bystanders as well as covertly film the harassment by pretending to check your email.

Practice resilience. “There is strength in recognizing that harassment hurts,” said Valdes. Rather than forcing away any negative emotions and pretending like the incident didn’t happen, resilience centers on reclaiming power through caring for yourself and your communities. This reclamation can manifest in a multitude of ways, whether it’s giving yourself the compassion to process things, tapping into interpersonal relationships, creating a dialogue within your workplace or supporting community organizations.

Violence prevention in the long term

Not all instances of anti-Asian violence can be stopped in the moment — nor does the process of healing end there. Instead, individual action should accompany more sweeping changes at the community level with the ultimate goal of addressing the reasons why violence occurs in the first place. Right now, the Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus — along with a long list of other Asian American organizations — is advocating for President Joe Biden to put $300 million toward turning these changes into a widespread reality.

Effectively rooting out hate requires “a long-term investment in low-income Asian communities and other communities of color,” Aarti Kohli, executive director of the Asian Law Caucus, told TODAY over Zoom. “A lot of these incidents are occurring in neighborhoods where people are struggling to keep jobs, to keep housing, and so there’s an economic component to what’s happening as well.”

Another key aspect of violence prevention is youth education, she explained, because so many anti-Asian hate crimes are committed by youth. Studies show that children can develop racial biases as early as ages 3 to 5. This means that introducing genuinely diverse curriculums early on — from teaching students about each others' histories in elementary school to mandating ethnic studies courses in high school — can have a major impact. Institutionalizing cross-racial conversations can bridge divides, both real and imagined.

Solidarity between Black and Asian communities

As more anti-Asian hate incidents are publicized, many social media users — in liberal and conservative circles alike — have implied that Black people are the primary perpetrators of anti-Asian violence, crafting a narrative that pits the Black and Asian communities against one another. Not only is the implication false — NPR’s "Code Switch" podcast found that white people carry out 90% of anti-Asian hate crimes — but it also erases both the prevalence of anti-Blackness in Asian communities and the long, storied history of solidarity.

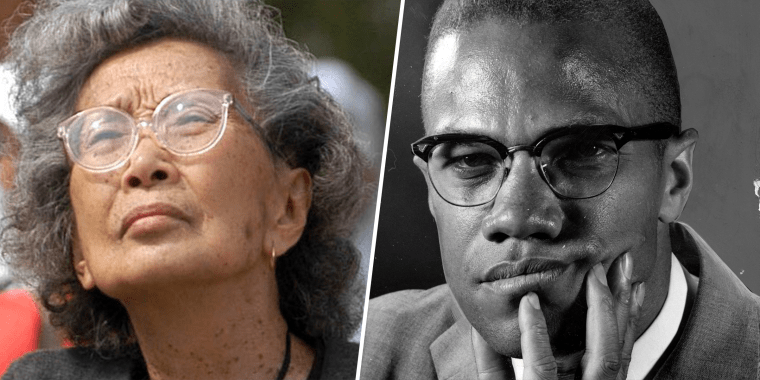

Ho, the critical race scholar, cited examples such as the 1992 Los Angeles riots following the Rodney King trial and the killing of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins by Soon Ja Du, a Korean convenience store owner, but also the Rainbow Coalition, Black-Asian solidarity against the Vietnam War, civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama’s work with Malcolm X and more. In response to social media users asking why people selectively speak out about Asian hate but not anti-Blackness, Ho said anti-racist work should inherently mean advocating for universal human rights and striving to dismantle the root of it all: white supremacy.

"There's a scarcity mentality that many of us work on... White supremacy wants us to be fighting and squabbling and saying there's only so much pie to go around, only so much attention span, only so many resources," said Ho, whose parents are Chinese but whose mother was raised in Jamaica. "Getting out of that framework requires a different kind of thinking and it requires one of more generosity and compassion.”

Community-based solutions

In the shorter term, community-based solutions to ward off violence right now can look like a “community ambassador program,” said Kohli. “A lot of our elderly people don’t want to necessarily walk next to a police officer. A lot of folks don’t necessarily speak English well. So to have people with them who are from the community, who are there to show care and protection, is one alternative.”

Moreover, Kohli explains that every situation of anti-Asian violence is different. For some, victims can viably pursue redress under legal pathways, but most don’t rise to the level of a crime that can be prosecuted. And regardless, she said, this country is reckoning with the fact that throwing people into an anti-Black criminal justice system — and afterward, into racially segregated jails — isn’t a cure for anything, let alone intolerance. Law enforcement's pattern of racist violence suggests that healing racial divides necessitates divesting from the notion of punishment as synonymous with justice.

Fortunately, community-based restorative justice practices can act as a meaningful stand-in. Restorative justice can look like a lot of things, Kohli explained, from candid conversations between the parties involved to community service. But across each iteration is a common thread: guiding the perpetrator toward taking responsibility for the harm they’ve caused.

“In the criminal legal system, it’s oppositional, so the tendency for people is to say ‘I didn’t do it' or deflect. The law isn’t set up for people to take responsibility,” said Kohli. “(Restorative justice) brings someone into a space of potential rehabilitation in a way that is much stronger than our criminal legal system.”