The amount of money spent per public school student fell in 2011 for the first time since the Census Bureau began keeping records more than three decades earlier, as economic woes finally caught up with educational realities.

“This is clearly the fallout from the Great Recession,” said Michael Petrilli, executive vice president of The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank.

The recession officially ran from December 2007 to June of 2009, but experts say there was some lag time before things like the housing bust began really hurting tax revenues, in turn crimping state and local budgets.

In addition, the federal government’s economic stimulus plan helped offset some of the initial tax revenue drops, so it took some time before state and local lawmakers had to tackle one of the least popular options: Cutting education funding.

“They tried to insulate education spending as best they could … but you just can’t protect it 100 percent,’ said Mike Griffith, school finance consultant for the Education Commission of the States, which provides data and analysis for state education systems.

Both liberal and conservative education policy experts agree that the drop was driven more by harsh economic realities rather than ideological preferences.

“It’s a tax issue at this point,” said Kim Rueben, a senior fellow with the Tax Policy Center and an expert on the economics of education.

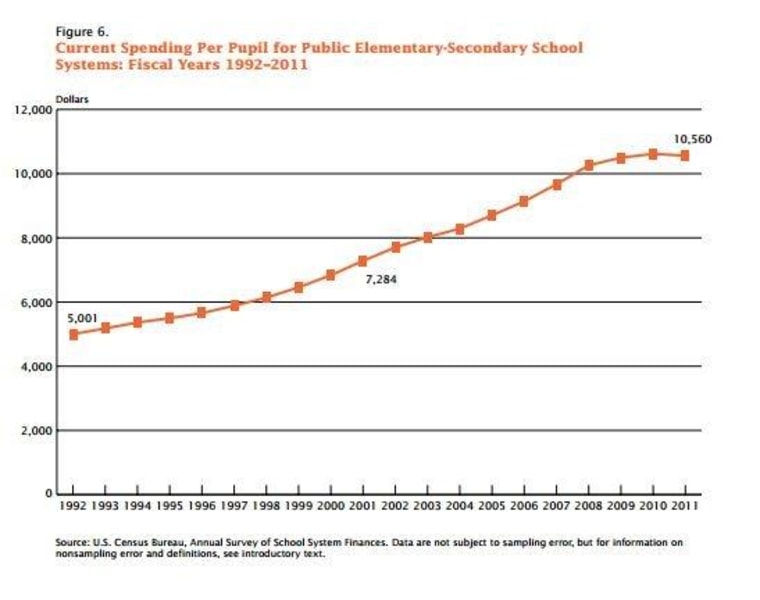

The 50 states and Washington, D.C. spent $10,560 per student in 2011, according to the most recent Census data, a less than 1 percent drop from 2010. Though tiny, it marked the first drop in per-pupil spending since the Census Bureau began collecting annual data in 1977.

Overall, public elementary and secondary school systems spent $595.1 billion in 2011, down 1.1 percent from 2010. It was the second year in a row that total expenditures fell. The data is not adjusted for inflation.

Many experts expect funding levels per student will stabilize and perhaps even start rising in the next few years, as improving economic conditions and a better housing market translates into higher tax revenues.

But they don’t expect dramatic improvements. And already, many say funding reductions have forced some school districts to take unprecedented steps, including cutting teachers.

“There (have) actually been declines in education employment, which is really different than in prior recessions, where state and local government has actually protected employment more,” Rueben said.

In addition, Griffith said schools have had to trim in other ways, such as reducing or charging for extracurricular activities and cutting transportation, technology and capital spending on things like building maintenance.

Others have had to take more drastic measures. In Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emanuel is locked in a heated battle over a decision to close 50 schools as the district faces a $1 billion deficit.

School districts have dealt with recessions before, but in the past Griffith said wealthier areas were often able to offset tax revenue cuts by passing levies or coming up with other funding options for schools. That meant that across the nation, spending per student has historically continued to rise even if certain districts saw spending fall.

This time, he said, so many districts were forced to make cuts that the national numbers finally reflected the hit. Nevertheless, some of the nation’s wealthiest areas were still likely able to maintain strong funding, potentially exacerbating the gap between rich and poor districts.

“The wealthy districts can go to the voters,” Griffith said. “The poorer communities aren’t able to do that.”

In general, state funding for education varies widely. States including New York, Washington, D.C. and Wyoming spent more than $15,000 per pupil in 2011, while Utah, Oklahoma and Mississippi spent less than $8,000 per student that year.

Rueben said funding per student can be higher because of an investment in quality education, but also for reasons having little to do with instruction. Some states have smaller school districts and thus more overhead costs, or a higher cost of living that translates into bigger salaries.

And when spending rises, it’s not necessarily translating into more resources in the classroom. In the coming years, Rueben and others also noted that more education funding is likely to be allocated to teacher pensions and health care benefits, potentially leaving less for classroom instruction.

Some say one potential silver lining to the nation’s education funding woes could be that states start thinking about smarter ways to spend money, such as combining administrative costs or using cheaper online learning options where appropriate.

Paul E. Peterson, director of Harvard University’s program on education policy and governance, said his data has shown a very small positive correlation between how much is spent per student and how well they do.

“It’s costing us a lot more, but are we getting anything out of it? That’s the question,” he said.