Joanna Quinn is the author of “The Whalebone Theatre,” her debut novel and the October pick for Read With Jenna’s book club. In a personal essay for TODAY, she writes about the lesson her fictional characters taught her about loss.

Do you remember the strange get-togethers we had in lockdown? When we would meet in a garden or a park and have socially distant picnics.

As someone with a February birthday, I was especially grateful for the family members who braved freezing weather to mark the day with me on a beach in 2021. It was the smallest of celebrations: We had flasks of tea, pieces of cake and flew kites.

It was also the last day we were all together before my stepfather, Chris, died. I had hardly seen him for months before, as we were in isolation, and I did not see him afterward, when he went into hospital for cancer treatment, as we were not allowed to visit. In hindsight, that day on the beach seems like a makeshift life raft — a bit of driftwood we climbed onto, briefly, before the current carried us apart.

Nine months later, my dad, Tony, also passed away. He suffered a fall and went into a hospital that was barely functioning, overwhelmed by the demands of the pandemic. By the time my sister and I got there, Dad had deteriorated so drastically we were only able to have him transferred to a hospice, where we stayed with him until he died.

It was disorientating to lose both of them in such rapid succession. And because I hadn’t seen them much during lockdown, their permanent absence seemed unreal, hard to believe. It didn’t seem possible they were no longer with us, especially as life began to return to normal.

As well as the shock of losing two much-loved men, I felt a particular pain. A small, childish disappointment — one I felt embarrassed admitting to, especially in the face of my mum’s grief at losing my stepdad, Chris, her partner for over 30 years. I was sad that they had died before my first novel was published. A sadness that felt trivial and egotistical.

“The Whalebone Theatre” had been sold to a publisher just before my stepdad died. He had been so excited by the news, ringing me up to congratulate me in the extra loud voice he used on the phone, then ringing all his friends. Dad too was delighted, and I was able to read him the first chapter when I was with him in the hospice.

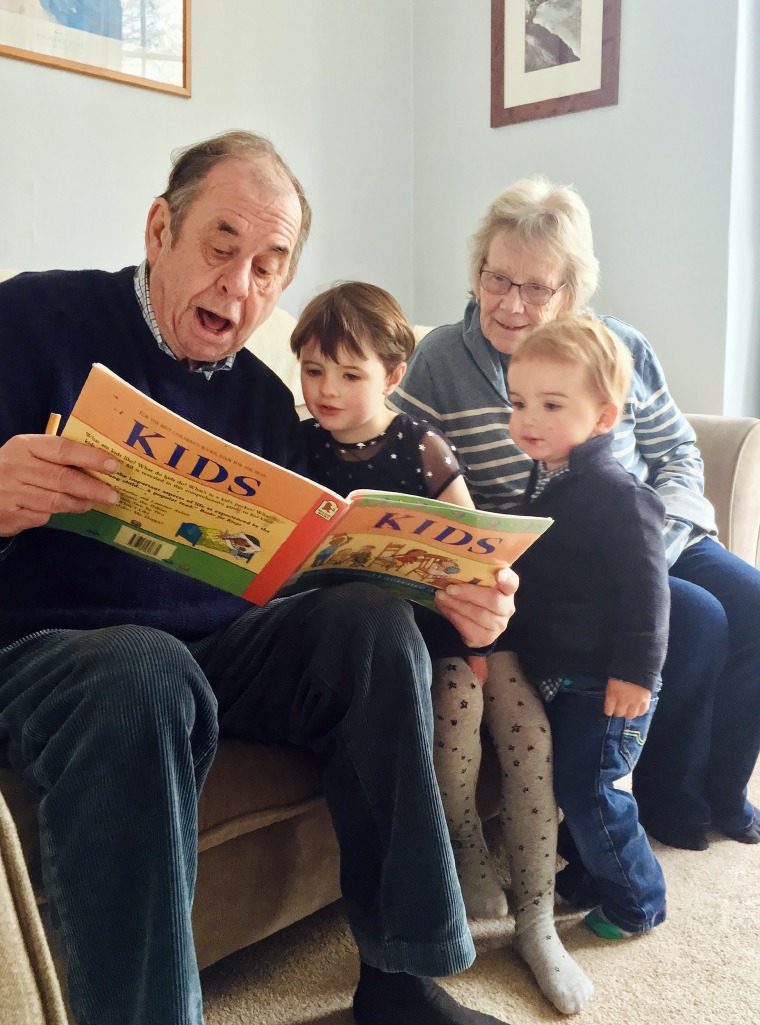

I was especially sorry that Dad wouldn’t get to read the finished thing, as many scenes were inspired by books we had enjoyed together. My parents divorced when I was young, and while Dad and I didn’t have the usual father-daughter relationship, we did share an interest in history.

Dad was born in 1937 and his first memories were of the Second World War, particularly the fighter planes that roared overhead. When he was a young man, the U.K. still had National Service, so Dad flew to Malaya and Singapore in a military uniform of his own — an eye-opening experience for a young man from a working-class Irish family.

Books were our common language, but Dad would never get to read mine. He would never see it in his local bookshop. And neither he nor Chris would get to turn to the back and see their names in the acknowledgements.

He remained interested in the experiences and stories of war all his life. I first learned about wartime spies in a book I bought for him and one of his last messages to me was a thank you for a book about code-breaking. Books were our common language, but Dad would never get to read mine. He would never see it in his local bookshop. And neither he nor Chris would get to turn to the back and see their names in the acknowledgements.

But as I went through my novel manuscript, getting it ready for publication, I realized I’d written about a very similar situation.

“The Whalebone Theatre” includes the Second World War and, when writing it, I had considered how war doesn’t just end lives, it takes away the futures people believed they would have.

My young characters had pictured their adult lives — a wedding in the village church or setting up a theater company — and they imagined the people who would be with them to see these things happen. But the war had dismantled their hopes like removal men, carrying off audience members and leaving empty chairs.

Our aspirations rarely feature us standing alone — we populate our daydreams with those who will share our happiness. The father who gives away the bride. The proud sibling who cheers from the crowd. What does our success mean if those people are no longer there? Is it even success without them? How can we celebrate?

Our aspirations rarely feature us standing alone — we populate our daydreams with those who will share our happiness. ... What does our success mean if those people are no longer there?

These were questions I was pondering, and curiously, my book had answers for me. One of my characters talks about how strange it is to celebrate victory when so many have been lost in the war, and another called Myrtle replies: “We must celebrate when we can, darling. It doesn’t come around often.”

I thought of Myrtle’s words on the night we launched my novel at a lovely party in a London bookshop. It was as if she was talking directly to me. She was right, too — it was important to seize these moments of joy, especially after the hard years of the pandemic. And what kind of ungracious grump would I be, if I gloomed my way through my own party?

My main character, Cristabel, also had a lesson for me. After the horror of war, amid personal sadness, she returns to the theater she has created from the skeleton of a whale and puts on a show for local children. She believes it is something “useful” she can do — that the show may still have value for others, even if it feels hollow to her, even if there are people missing from the audience.

The publication of my book turned out to be something “useful” for my Mum. A happy distraction for her, during a time when much else was bleak and there was an empty seat in her house. It was a little life raft, like my birthday on the beach. It is strange, but when you write a novel, you are so wrapped up in your own creation, you rarely consider what it might mean for other people. It has been a gift to see my book go out into the world and have a life beyond me.

Musician Nick Cave has written about the “uncanny foresight” of his songs. He discusses the idea that they might be mysterious channels for intuition and movingly describes how this notion was a comfort to him after his son’s death. He says: “You write a line that requires the future to reveal its meaning.”

These days, I have come to believe that creativity — whether songwriting or fiction — can occasionally allow us to access that wiser, instinctive, far-reaching part of our brain that tells us things we know but often forget. Sometimes, if we’re lucky, it also teaches us lessons we will one day really need to know.