The clandestine U.S. commandos whose job is to capture or kill Osama bin Laden have not received a credible lead in more than two years. Nothing from the vast U.S. intelligence world — no tips from informants, no snippets from electronic intercepts, no points on any satellite image — has led them anywhere near the al-Qaeda leader, according to U.S. and Pakistani officials.

"The handful of assets we have have given us nothing close to real-time intelligence" that could have led to his capture, said one counterterrorism official, who said the trail, despite the most extensive manhunt in U.S. history, has gone "stone cold."

But in the last three months, following a request from President Bush to "flood the zone," the CIA has sharply increased the number of intelligence officers and assets devoted to the pursuit of bin Laden. The intelligence officers will team with the military's secretive Joint Special Operations Command(JSOC) and with more resources from the National Security Agency and other intelligence agencies.

Bin Laden ‘off the net’

The problem, former and current counterterrorism officials say, is that no one is certain where the "zone" is.

"Here you've got a guy who's gone off the net and is hiding in some of the most formidable terrain in one of the most remote parts of the world surrounded by people he trusts implicitly," said T. McCreary, spokesman for the National Counterterrorism Center. "And he stays off the net and is probably not mobile. That's an extremely difficult problem."

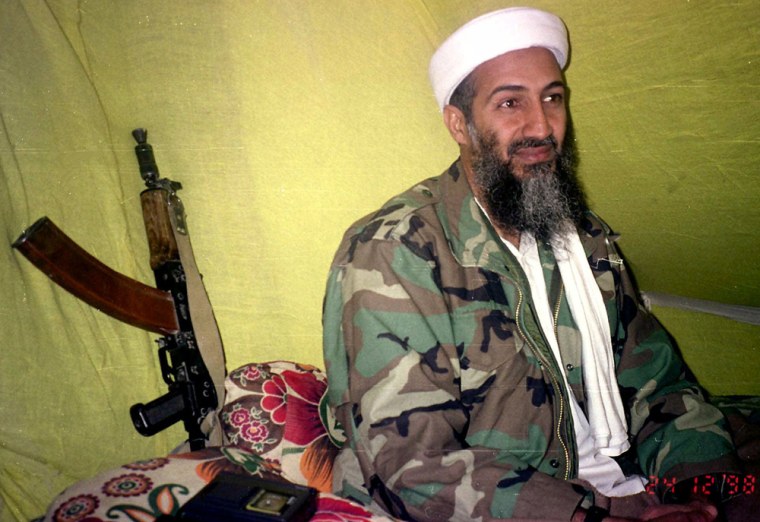

Intelligence officials believe that bin Laden is hiding in the northern reaches of the autonomous tribal region along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. This calculation is based largely on a lack of activity elsewhere and on other intelligence, including a videotape, obtained exclusively by the CIA and not previously reported, that shows bin Laden walking on a trail toward Pakistan at the end of the battle of Tora Bora in December 2001, when U.S. forces came close but failed to capture him.

Many factors have combined in the five years since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks to make the pursuit more difficult. They include the lack of CIA access to people close to al-Qaeda's inner circle; Pakistan's unwillingness to pursue him; the reemergence of the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan; the strength of the Iraqi insurgency, which has depleted U.S. military and intelligence resources; and the U.S. government's own disorganization.

But the underlying reality is that finding one person in hiding is difficult under any circumstances. Eric Rudolph, the confessed Olympics and abortion clinic bomber, evaded authorities for five years, only to be captured miles from where he was last seen in North Carolina.

No real signs of ‘Elvis’

It has been so long since there has been anything like a real close call that some operatives have given bin Laden a nickname: "Elvis," for all the wishful-thinking sightings that have substituted for anything real.

After playing down bin Laden's importance and barely mentioning him for several years, Bush last week repeatedly invoked his name and quoted from his writings and speeches to underscore what Bush said is the continuing threat of terrorism.

Many terrorism experts, however, say the importance of finding bin Laden has diminished since Bush first pledged to capture him "dead or alive" in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks. Terrorists worldwide have repeatedly shown they no longer need him to organize or carry out attacks, the experts say. Attacks in Europe, Asia and the Middle East were perpetrated by homegrown terrorists unaffiliated with al-Qaeda.

"Will his capture stop terrorism? No," Rep. Jane Harman (D-Calif.), vice chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, said in a recent interview. "But in terms of a message to the world, it's a huge message."

Despite a lack of progress, at CIA headquarters bin Laden and his deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, are still the most wanted of the High Value Targets, referred to as "HVT 1 and 2." The CIA station in Kabul still offers a briefing to VIP visitors that declares: "We are here for the hunt!" -- a reminder that finding bin Laden is a top priority.

Gary Berntsen, the former CIA officer who led the first and last hunt for bin Laden at Tora Bora, in December 2001, says, "This could all end tomorrow." One unsolicited walk-in. One tribesman seeking to collect the $25 million reward. One courier who would rather his kids grow up in the United States. One dealmaker, "and this could all change," Berntsen said.

Pakistanis: Bin Laden still alive

On the videotape obtained by the CIA, bin Laden is seen confidently instructing his party how to dig holes in the ground to lie in undetected at night. A bomb dropped by a U.S. aircraft can be seen exploding in the distance. "We were there last night," bin Laden says without much concern in his voice. He was in or headed toward Pakistan, counterterrorism officials believe.

That was December 2001. Only two months later, Bush decided to pull out most of the special operations troops and their CIA counterparts in the paramilitary division that were leading the hunt for bin Laden in Afghanistan to prepare for war in Iraq, said Flynt L. Leverett, then an expert on the Middle East at the National Security Council.

"I was appalled when I learned about it," said Leverett, who has become an outspoken critic of the administration's counterterrorism policy. "I don't know of anyone who thought it was a good idea. It's very likely that bin Laden would be dead or in American custody if we hadn't done that."

Several officers confirmed that the number of special operations troops was reduced in March 2001.

White House spokeswoman Michele Davis said she would not comment on the specific allegation. "Military and intelligence units move routinely in and out," she said. "The intelligence and military community's hunt for bin Laden has been aggressive and constant since the attacks."

The Pakistani intelligence service, notoriously difficult to trust but also the service with the best access to al-Qaeda circles, is convinced bin Laden is alive because no one has ever intercepted or heard a message mourning his death. "Al-Qaeda will mourn his death and will retaliate in a big way. We are pretty sure Osama is alive," Pakistan's interior minister, Aftab Khan Sherpao, said in a recent interview with The Washington Post.

Sources describe meeting

Pakistani intelligence officials also say they believe bin Laden remains actively involved in al-Qaeda activities. They cite the interrogations of Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, a key planner of the bombings of two U.S. embassies in East Africa in 1998, and Abu-Faraj al-Libbi, who served as a communications conduit between bin Laden and senior al-Qaeda operatives until his capture last year.

Libbi and Ghailani, who was arrested in Pakistan in July 2004, were the last two people taken into custody to have met with and taken orders from Zawahiri and to hear directly from bin Laden. "Both Ghailani and Libbi were informed that Osama was well and alive and in the picture by none other than Zawahiri himself," one Pakistani intelligence official said.

Two Pakistani intelligence officials recently interviewed in Karachi said that the last time they received firsthand information on bin Laden was in April 2003, when an arrested al-Qaeda leader, Tawfiq bin Attash, disclosed having met him in the Khost province of Afghanistan three months earlier.

Attash, who helped plan the 2000 USS Cole bombing, told interrogators that the meeting took place in the Afghan mountains about two hours from the town of Khost.

By then, Pakistan was the United States' best bet for information after an infusion of funds from the U.S. intelligence community, particularly in the area of expensive NSA eavesdropping equipment.

"For technical intelligence ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence) works hand in hand with the NSA," a senior Pakistani intelligence official said. "The U.S. assistance in building Pakistan's capabilities for technical intelligence since 9/11 is superb."

Boots on the ground

Since early 2002, the United States has stationed a small number of personnel from NSA and CIA near where bin Laden may be hiding. They are embedded with counterterrorism units of the Pakistan army's elite Special Services Group, according to senior Pakistani intelligence officials.

The NSA and other specialists collect imagery and electronic intercepts that their CIA counterparts then share with the Pakistani units in the tribal areas and with the province of Baluchistan to the south.

But even with sophisticated technology, the local geography presents formidable obstacles. In a land of dead-end valleys, high peaks and winding ridge lines, it is easy to hide within the miles of caves and deep ravines, or to live unnoticed in mud-walled compounds barely distinguishable from the surrounding terrain.

The Afghan-Pakistan border is about 1,500 miles. Pakistan deploys 70,000 troops there. Its army had never entered the area until October 2001, more than a half century after Pakistan's founding.

Pakistani sources lost

A Muslim country where many consider bin Laden a hero, Pakistan has grown increasingly reluctant to help the U.S. search. The army lost its best source of intelligence in 2004, after it began raids inside the tribal areas. Scouts with blood ties to the tribes ceased sharing information for fear of retaliation.

They had good reason. At least 23 senior anti-Taliban tribesmen have been assassinated in South and North Waziristan since May 2005. "Al-Qaeda footprints were found everywhere," Interior Minister Sherpao said in a recent interview. "They kidnapped and chopped off heads of at least seven of these pro-government tribesmen."

Pakistani and U.S. counterterrorism and military officials admit that Pakistan has now all but stopped looking for bin Laden. "The dirty little secret is, they have nothing, no operations, without the Paks," one former counterterrorism officer said.

Last week, Pakistan announced a truce with the Taliban that calls on the insurgent Afghan group to end armed attacks inside Pakistan and to stop crossing into Afghanistan to fight the government and international troops. The agreement also requires foreign militants to leave the tribal area of North Waziristan or take up a peaceable life there.

In Afghanistan, the hunt for bin Laden has been upstaged by the reemergence of the Taliban and al-Qaeda, and by Afghan infighting for control of territory and opium poppy cropland.

Neither here nor there

Lt. Gen. John R. Vines, who commanded U.S. troops in Afghanistan in 2003, said he believes that bin Laden kept close to the border, not wandering far into either country. That belief is still current among military and intelligence analysts today.

"We believe that he held to a pretty narrow range of within 15 kilometers of the border," said Vines, who now commands the XVIII Airborne Corps, "so that if the Pakistanis, for whatever reason, chose to do something to him, he could cross into Afghanistan and vice versa."

He said he believes that bin Laden's protection force "had a series of outposts with radios that could alert each other" if helicopters were coming or other troop movements were evident.

Pakistani military officials in Wana, the capital of South Waziristan, described bin Laden as having three rings of security, each ring unaware of the movements and identities of the other. Sometimes they communicated with specially marked flashlights. Sometimes they dressed as women to avoid detection by U.S. spy planes.

Pakistan will permit only small numbers of U.S. forces to operate with its troops at times and, because their role is so sensitive politically, it officially denies any U.S. presence. A frequent complaint from U.S. troops is that they have too little to do. The same complaint is also heard from U.S. forces in Afghanistan, where there were few targets to go after.

Although the hunt for bin Laden has depended to a large extent on technology, until recently unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) were in short supply, especially when the war in Iraq became a priority in 2003.

Simple but effective means of hiding

In July 2003, Vine said that U.S. forces under his command believed they were close to striking bin Laden, but had only one drone to send over three possible routes he might take. "A UAV was positioned on the route that was most likely, but he didn't go that way," said Vines. "We believed that we were within a half hour of possibly getting him, but nothing materialized."

Faced with the most sophisticated technology in the world, bin Laden has gone decidedly low-tech. His 17 video or audiotapes in the last five years are believed to have been hand-carried to news outlets or nearby mail drops by a series of couriers who know nothing about the contents of their deliveries or the real identity of the sender, a simple method used by spies and drug traffickers for centuries.

"They are really good at operational security," said Ben Venzke, chief executive officer of IntelCenter, a private company that analyzes terrorist information and has obtained, analyzed and published all bin Laden's communiques. "They are very good at having enough cut-outs" to move videos into circulation without detection. "It's some of the simplest things to do."

Uncertain command structure

Bureaucratic battles slowed down the hunt for bin Laden for the first two or three years, according to officials in several agencies, with both the Pentagon and the CIA accusing each other of withholding information. Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld's sense of territoriality has become legendary, according to these officials.

In early November 2002, for example, a CIA drone armed with a Hellfire missile killed a top al-Qaeda leader traveling through the Yemeni desert. About a week later, Rumsfeld expressed anger that it was the CIA, not the Defense Department, that had carried out the successful strike.

"How did they get the intel?" he demanded of the special operations and other military personnel in a high-level meeting, recalled one person knowledgeable about the meeting.

Gen. Michael V. Hayden, then director of the National Security Agency and technically part of the Defense Department, said he had given it to them.

"Why aren't you giving it to us?" Rumsfeld wanted to know.

Hayden, according to this source, told Rumsfeld that the information-sharing mechanism with the CIA was working well. Rumsfeld said it would have to stop.

Infighting over control

A CIA spokesman said Hayden, now the CIA director, does not recall this conversation. Pentagon spokesman Bryan Whitman said, "The notion that the department would do anything that would jeopardize the success of an operation to kill or capture bin Laden is ridiculous." The NSA continues to share intelligence with the CIA and the Defense Department.

At that time, Rumsfeld was putting in place his own aggressive plan, led by the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM), to dominate the hunt for bin Laden and other terrorists. The overall special operations budget has grown by 60 percent since 2003 to $8 billion in fiscal year 2007.

Rows and rows of temporary buildings sprang up on SOCOM's parking lots in Tampa as Rumsfeld refocused the mission of a small group of counterterrorism experts from long-term planning for the war on terrorism to manhunting. The group "went from 20 years to 24-hour crisis-mode operations," one former special operations officer said. "It went from planning to manhunting."

In 2004, Rumsfeld finally won the president's approval to put SOCOM in charge of the "Global War on Terrorism."

Who’s calling the shots?

Today, however, no one person is in charge of the overall hunt for bin Laden with the authority to direct covert CIA operations to collect intelligence and to dispatch JSOC units. Some counterterrorism officials find this absurd. "There's nobody in the United States government whose job it is to find Osama bin Laden!" one frustrated counterterrorism official shouted. "Nobody!"

"We work by consensus," explained Brig. Gen. Robert L. Caslen Jr., who recently stepped down as deputy director of counterterrorism under the Joint Chiefs of Staff. "In order to find Osama bin Laden, certain departments will come together. . . . It's not that effective, or we'd find the guy, but in terms of advancing United States power for that mission, I think that process is effective."

But Lt. Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal, the JSOC commander since 2003, has become the de facto leader of the hunt for bin Laden and developed a good working relationship with the CIA to the point where he recently persuaded the former station chief in Kabul to become his special assistant. He asks for targets from the CIA, and it tries to comply. "We serve the military," one intelligence officer said.

McChrystal's troops have shuttled between Afghanistan and Iraq, where they succeeded in killing al-Qaeda leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and killed or captured dozens of his followers.

Under McChrystal, JSOC has improved its ability to quickly turn captured documents, computers and cellphones into leads and then to act upon them, while waiting for more analysis from CIA or SOCOM.

Industry experts and military officers say they are being aided by computer forensic field kits that let technicians retrieve information from surviving hard drives, cellphones and other electronic devices, as was the case in the Zarqawi strike.

Clandestine strikes come up short

McChrystal, who has commanded JSOC since 2003, now has the authority to go after bin Laden inside Pakistan without having to seek permission first, two U.S. officials said.

"The authority," one knowledgeable person said, "follows the target," meaning that if the target is bin Laden, the stakes are high enough for McChrystal to decide any action on his own. The understanding is that U.S. units will not enter Pakistan, except under extreme circumstances, and that Pakistan will deny giving them permission.

Such was the case in early January, when JSOC troops clandestinely entered the village of Saidgai, two officials familiar with the operation said, and Pakistan protested.

A week later, acting on what Pakistani intelligence officials said was information developed out of Libbi's interrogation, the CIA ordered a missile strike against a house in the village of Damadola, about 120 miles northwest of Islamabad, where Pakistani and American officials believed Zawahiri to be hiding.

The missile killed 13 civilians and several suspected terrorists. But Zawahiri was not among them. The strike "could have changed the destiny of the war on terror. Zawahiri was 100 percent sure to visit Damadola . . . but he disappeared at the last moment," one Pakistani intelligence official said.

Tens of thousands of Pakistanis staged an angry anti-American protest near Damadola, shouting, "Death to America!"

"Once again, we have lost track of Ayman al-Zawahiri," the Pakistani intelligence official said in a recent interview. "He keeps popping on television screens. It's miserable, but we don't know where he or his boss are hiding."

Contributing to this report were staff writers Bradley Graham, Thomas E. Ricks, Josh White, Griff Witte and Allan Lengel in Washington, Kamran Khan in Islamabad and John Lancaster in Wana, Pakistan, and staff researchers Julie Tate and Robert E. Thomason.