In the summer of 2019, Dirk Jansheski, then 3, suddenly stopped walking. Mom Rachel Jansheski noticed his leg was swollen and took him to an orthopedic doctor. His X-rays looked fine and Dirk started walking again, so it seemed he had recovered. A month later, he stopped walking again and wailed in agony.

“He slept very little. We spent a couple of days that way before we finally pushed with our pediatrician,” Jansheski of Grand Rapids, Michigan, told TODAY.com. “She saw him in person and realized it was way more than it seemed.”

Doctors found four lesions and diagnosed Dirk with high-risk stage 4 neuroblastoma, a cancer that mostly occurs in immature nerve cells in several areas of the body, often starting in the adrenal glands, according to National Cancer Institute.

“It’s a really aggressive, fast-growing cancer,” Jansheski said. “His tumor location is actually in his pelvis, and it grew to the size of a grapefruit or cantaloupe.”

After his diagnosis on July 26, 2019, he started aggressive treatment. Originally, it was supposed to last 16 months, but doctors added additional chemotherapy and radiation. He also had a massive resection surgery, underwent a stem cell transplant in February 2020 and received immunotherapy.

“He has been through pretty much every kind of cancer treatment option to make sure that it doesn’t grow back because stage 4, high-risk is so aggressive. They attack it with everything they have,” she said. “It has a 50% survival rate.”

While Dirk, now 7, is also in a clinical trial for a drug, only two of the therapies he received were approved for neuroblastoma. Jansheski said he received treatments commonly used for adult tumors, such as ovarian or testicular cancer. Sometimes the insurance company didn’t want to pay for protocols not officially authorized for Dirk’s cancer.

“Our team has had to fight our insurance (company) a couple different times,” Jansheski explained.

Dirk finished treatment in November 2020, but he still takes drugs to help with lingering side effects.

Jansheski worries about what would happen if he relapses. There’s no treatment protocol for children with recurring neuroblastoma, so they’re unsure what options he’d have. Every time Dirk goes for a scan, she stresses.

“They consider childhood cancer to be rare. That’s why it doesn’t get as much funding as other cancers,” she said. “You’re talking about a 3-year-old who could have 70-plus years of life ahead of them. It feels like we should give them a little bit more than the small percentage of funding they get right now.”

Only 4% of funding

The Children’s Cancer Research Fund, other organizations and families with children with cancer often repeat a commonly heard statistic: Only 4% of federal funding goes to researching childhood cancers.

“Not all research is labeled as pediatric cancer or breast cancer or lung cancer,” Dr. Stephen Hunger, director of the Center for Childhood Cancer Research at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told TODAY.com. “If you look at (National Cancer Institute) funding, 4% is about the percentage that is devoted to what is clearly pediatric cancer. The issue is that there’s a lot of basic research that is seeking to understand the mechanisms of how you develop cancer that may be applicable to pediatric cancer. But it’s not labeled as such.”

One reason adult cancer funding receives more money is because only about a quarter of adult cancers are rare.

“Most of the funding goes to adult cancers, and they are a lot more common,” Dr. Brigitte Widemann, head of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics section at the National Cancer Institute, told TODAY.com. “We firmly believe — I think all of the pediatric oncologists do — that each and every pediatric patient deserves the best understanding and treatment for their cancers.”

One challenge facing researchers when it comes to pediatric cancer is recruiting patients.

“All pediatric cancers are rare,” Widemann said. “Within the rare cancers, there is still a wide range, from tumors that occur maybe several thousand per year in the United States and pediatric patients with tumors that occur maybe only 30 per year.”

For children with cancers that occur so infrequently, finding enough patients to conduct a clinical trial of treatment can be tough. That’s why national collaboration remains essential for understanding rare types of pediatric cancers.

Still, researchers wish there were more funding.

“We definitely need more funding for pediatric cancer research,” Dr. Andrew Bukowinski, an assistant professor of pediatrics at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, told TODAY.com. “You have a group of patients that need to be living out the rest of their lives.”

Collaboration leads to ‘incredible advances’

Over the years, Dr. James Fahner said pediatric oncologists have done a lot with a little and made great strides.

“We have seen incredible advances in the availability of effective therapies and in the eventual cure of more and more types of childhood cancer,” the emeritus division chief of pediatric hematology/oncology at Corewell Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Michigan, told TODAY.com. “(Still) cancer actually remains the leading cause of death due to disease in young children.”

Take the example of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). At one point, children diagnosed with ALL survived an average of six months, but now, the cure rate is 85% percent, according to a report in Seminars in Oncology, looking at 50 years of cancer research.

“We have seen many diseases that were previously an almost certain death sentence for children with these types of cancer to now have incredibly high cure rates of 80, 85, 90%, which is incredibly gratifying,” Fahner explained. “If you were looking for a very positive, very impactful return on your research dollar investment, then children’s cancer is one of the miracles stories of modern medicine.”

Bukowinski said that consortiums, such as the Children’s Oncology Group, comprised of 200 pediatric cancer institutes, help advance pediatric cancer research.

“It allows us to share information and ask important questions,” he said. “We have done an excellent job in terms of improving outcomes in pediatric patients with cancer.”

Widemann added that the NCI has resources, including My Pediatric and Adult Rare Tumor Network (MyPART) and the NCI’s Rare Cancer Clinic. Families can visit the National Institutes of Health to be enrolled in studies and treated.

While devoting more funding and resources will help advance treatments, the experts agree that families also need robust social support.

“The burden of pediatric cancer is much higher,” Hunger said. “There’s probably no more impactful thing that occurs in most families’ lives than having a child diagnosed with a potentially fatal disease. ... People whose children die of cancer, they find a way to move on, but they’re never the same.”

Life after cancer

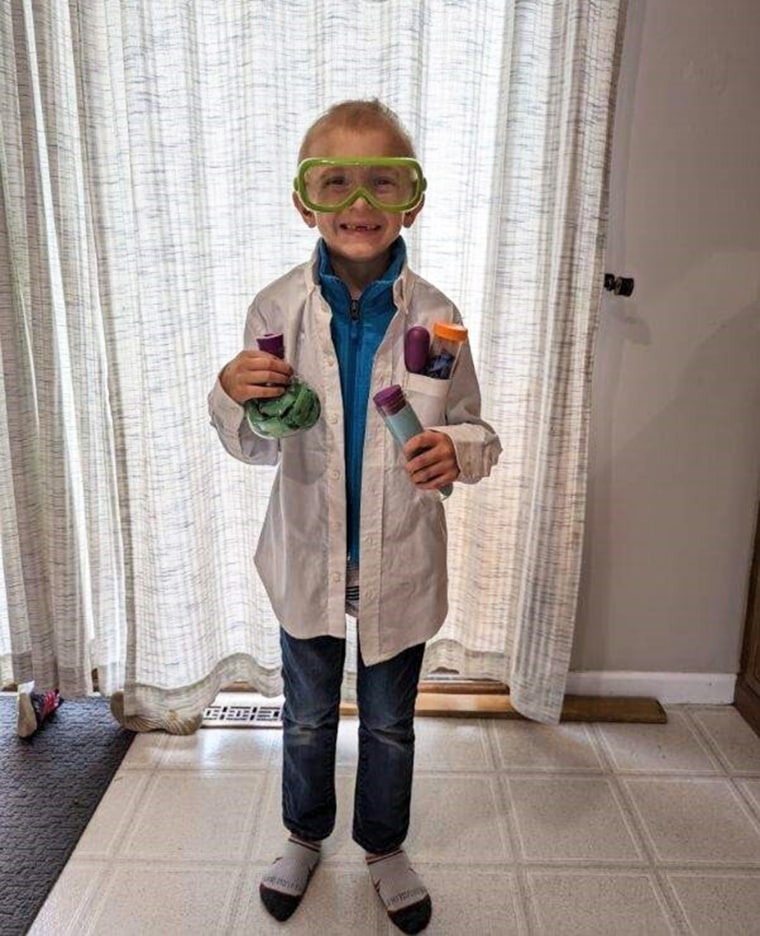

Dirk still has some cancer in his body, but recent scans revealed it’s not growing. Now in second grade, Dirk loves Marvel and all superheroes and spends time building Legos and playing Pokemon. He’s begun enjoying sports, taking golfing and swimming lessons, attending basketball camp and trying tennis and volleyball.

“He just loves to try new things,” Jansheski said.

This is a recent change, though. Last summer, Dirk experienced troubling side effects from cancer treatment. He complained of pain, dropped weight and lost the little bit of hair he had regrown.

“In the last year, we’ve been able to figure those out and treat them appropriately,” Jansheski said.

Some of the lingering symptoms were expected, but the list of Dirk’s complications feels overwhelming at times. Dirk has mild hearing loss from one of the chemotherapies and began wearing hearing aids in 2021, Jansheski said.

After he complained of back pain, the family learned that the radiation scarred his spine. He also has osteopenia, an early stage of osteoporosis, and too much iron in his liver. To treat this, he undergoes regular blood draws to lower the amount of iron in his body. He also has pancreatic insufficiency, where the pancreas stops excreting an enzyme that helps absorb fats ajd protein. Dirk takes a medication that helps with this condition and he’s gaining some weight.

“His body was not getting the nutrients it needed and so he was having hair loss,” Jansheski said.

He also developed specific antibody deficiency, which means his immune system doesn’t remember past infections or have a mechanism to fight them off. So when he gets a cold or the flu, he becomes really ill.

“It’s all-consuming for the rest of your child’s life,” Jansheski explaind. “There are many kids that pass away from complications from their treatments. It’s not just the cancer itself. So, it’s not like we’re done with treatment, we celebrate, and we move on with life. It really sticks around.”

The family knew that Dirk would experience some side effects of treatment, such as possible infertility and secondary cancers. Still, the Jansheski family longs for pediatric cancer treatments that quash the cancer without leaving children with so many complications.

“I don’t wish this on anybody,” Jansheski said. “We need to find better treatments that don’t cause all these side effects.”