When Marian Smith walked, she became short of breath. She was in her first trimester of her first pregnancy and assumed her trouble breathing was simply part of it. After a concerned colleague told her to talk to her doctor about it, Smith eventually learned she had a congenital heart condition, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) — a hole between the upper chambers of her heart. Her symptoms were severe and doctors wanted to fix it before she gave birth.

“It was hard to believe given the fact that I was so active,” Smith, 34, of Stamford, Connecticut, tells TODAY.com. “This was all brand new. I was just like, ‘Oh my goodness. My healthy lifestyle is to prevent what has happened in my family with heart disease.’ This was unknown territory.”

Trouble breathing isn’t a pregnancy symptom

After trying to have a baby for about two years, Smith and her husband, Aleahue Abu, felt thrilled when she was pregnant. A few weeks into her pregnancy, Smith started experiencing trouble breathing when she was standing or walking. She felt surprised by it — she was a yoga instructor and had run half-marathons, in part, because of a family history of heart disease.

“I just passed it off as would this be normal with pregnancy because what do I know? This is my first pregnancy,” she says. “It was hard to walk up stairs. Everyday living became a challenge. Just everyday mobility became a challenge. I realized something was strange about it. But everyone says pregnancy is different for everyone so this must be normal for me.”

Soon others noticed that Smith was struggling.

“(My coworker) said, ‘Why are you walking so slow? You seem so out of breath,’” Smith recalls. “I was like, ‘I’m pregnant, that’s why.’ And she was like, ‘You need to go talk to someone.’ And that’s when it dawned on me that something might be wrong.”

Smith visited her OB-GYN who connected her to a cardiologist.

“At the time (I thought), ‘I’m having a problem with my breathing, why do I need to talk to a cardiologist,’” she says. “They suspected right away that it might be something going on with my heart.”

The doctor noticed her oxygen levels were normal when Smith rested but they plummeted when she moved, “which caused a sense of panic.” Doctors admitted her to the local hospital in Connecticut where they tried to figure out what was occurring before consulting with doctors at NYU Langone Health in New York City. Eventually she was transferred to NYU. That’s when she learned she had a PFO and would need to undergo surgery in her second trimester.

“They realized the severity of how much my oxygen level was dropping,” she said. “(This) brought up a lot of emotions.”

Most people don’t know they have a PFO until something happens

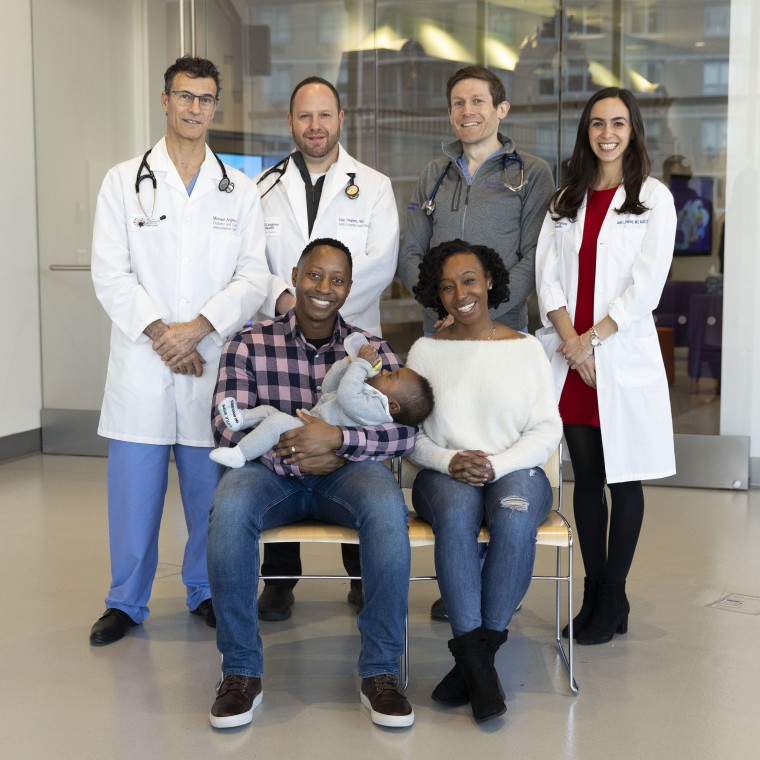

While Smith was in the local hospital, her doctors contacted Dr. Dan Halpern, a cardiologist and medical director of the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program at NYU Langone Health, for consultation to make the final diagnosis. When Smith transferred to NYU Langone Health, Halpern and his colleagues needed to decide what to do.

In some cases, the PFO, isn’t so severe that it requires immediate treatment. PFOs start in everyone when babies develop in utero when there is an opening between the upper chambers of their hearts. For most people, these holes close. In some cases, they do not.

“In most of us, it seals closed. Tissue essentially grows together, essentially and permanently makes a closed structure. But in about one out of five people, that last part — the sealing of the flap against the wall between the upper chambers — never really happened,” Dr. Michael Argilla, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Pediatric Catheterization Laboratory at NYU Langone Health, tells TODAY.com. “In (Smith’s) case that was happening where she would stand up, the flap would open and would let blood flow past from right to left.”

Her oxygen saturation levels dipped dramatically when she’d move, going from a normal 99 at resting to about 85 with movement.

“In order to get it down to 85 that’s a lot of blood mixing,” Halpern tells TODAY.com. “You have to be sick. You have to have a lot of blood mixing and that’s really the reason why we thought it would be important to tackle it during the pregnancy.”

That meant her medical team needed to decide the best timing and how to protect Smith and the baby from radiation used to perform the procedure to fix the hole.

“Everybody agreed that after 16 weeks, all the organs have formed so it’s probably the safest,” Halpern says. “We did it on the 18th week.”

Most people don’t know they have a PFO until something happens, such as a stroke or breathing problems. Sometimes people learn they have congenital heart conditions while pregnant.

“Pregnancy in itself is a strain on your heart because the amount of blood you have to pump for the uterus, placenta and the baby as it’s growing significantly increases,” Dr. Meghana Limaye, a maternal fetal medicine specialist in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at NYU Langone Health, tells TODAY.com. “Sometimes people do present for the first time (with heart conditions) because that’s the first time their heart has really been put under this type of stress.”

Doctors believed Smith's needed to be fixed because her PFO had an "unusual" presentation. Smith's oxygen dropped dramatically when she exerted herself and she needed supplemental oxygen. And she was at greater risk because pregnancy can increase the number of clots people experience. If a clot passed through that hole, she and the baby could be in danger.

“Pregnancy is a period where actually you have more blood clots,” Halpern says. “Having this kind of connection, this kind of hole, what we call shunting, could have an outcome of stroke, could throw clots to other organs.”

Argilla performed the procedure to close the hole while Limaye observed mom and baby. To protect the baby from too much radiation, her medical team adjusted the doses.

“The primary method we focus on an ultrasound and then supplemented that with the fluoroscope imaging whenever that was necessary, which was minimal,” Argilla says. “I was just looking at the dose we ended up using. It’s really only a couple of times the background radiation dose a fetus would receive just walking around inside mom over time.”

Argilla inserted a catheter in a vein in the top of her leg to thread the device up into her heart. It works like a plug, stopping the flap from opening.

“PFOs in generally are very successfully closed using a cath lab and usually for a one-time procedure with no need for follow up or repeat procedure,” he says.

Surgery and a successful delivery

The days leading up to the procedure felt overwhelming for Smith. While she was nervous about undergoing a heart procedure, she was becoming increasing uncomfortable.

“I was really confined to my apartment because of the inability to move without having to stop and take deep breaths or chug around a huge oxygen tank just to live,” she says. “I was ready for it.”

Waking up from anesthesia “was like a breath of fresh air.”

“There’s a sense of freedom and a sense of joy on the other side of it,” she says.

The rest of her pregnancy was uneventful, and she delivered her son Idenara Abu on April 8, 2022.

“I got to deliver the way I wanted to deliver, which was a vaginal birth,” Smith says.

Limaye says Smith's recovery and later delivery went very well.

“It was amazing after the PFO was repaired, she immediately felt better,” she says. “It’s amazing how quickly she felt better.”

Smith says she hopes her story encourages other people to seek medical care when something seems wrong.

“A lot of time’s there’s a stigma, like ‘I’m young, I don’t have to worry about that.’ You do,” she says. “You’re never too young or too old to have a condition. You need to listen, and you need to advocate for yourself.”

CORRECTION (Feb. 16, 2023 at 9:09 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Limaye's role at Smith's delivery. She was not present at Smith's induction.