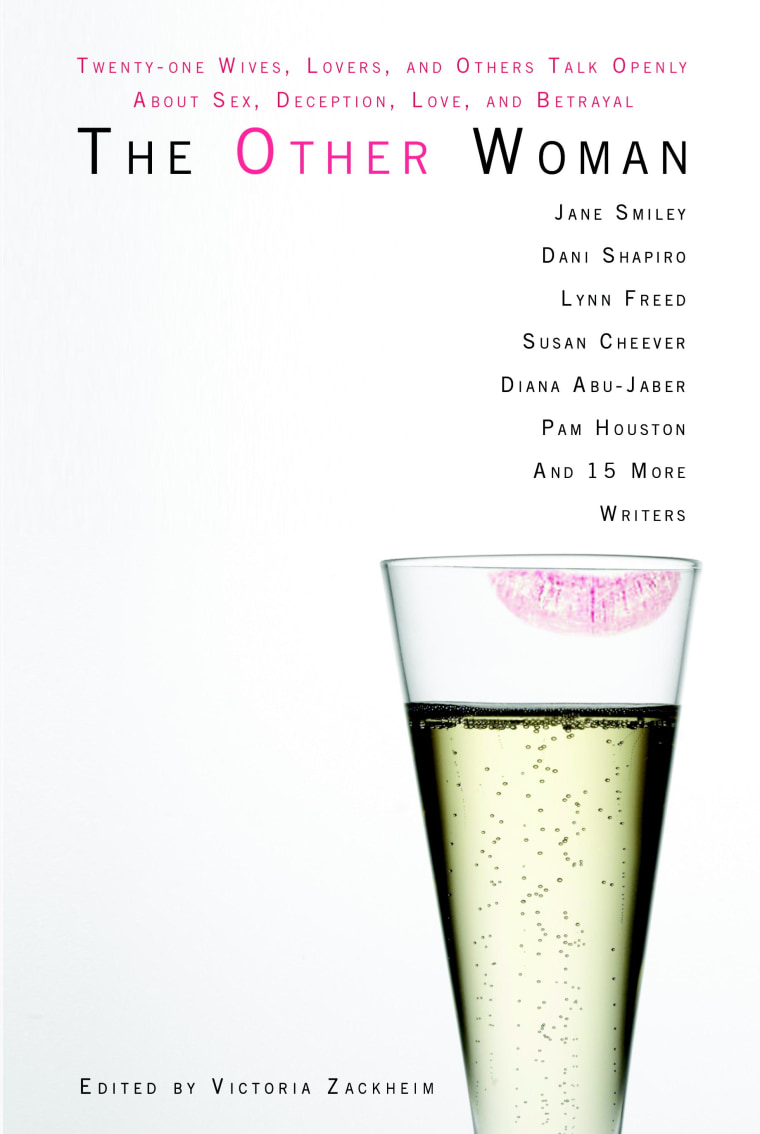

In "The Other Woman: Twenty-one Wives, Lovers, and Others Talk Openly About Sex, Deception, Love, and Betrayal," Victoria Zackheim shares 21 essays of love, betrayal, shock and jealousy by women who either broke up relationships or those who suffered at the hands of "home-wrecker" or "Jezebel." Here's an excerpt:

Here's the thing about the other woman. She lives inside your head. She may live on the next street or in the next town or halfway across the world; she may be five-two or five-nine; she may be rail thin (never skinny) or voluptuous (never fat). But however big or small she is, however much space she takes up in the world, will never compare to the amount of space she'll take up in your brain. It is there that she will spread herself from wall to wall, eating gift-wrapped chocolates-so many gift-wrapped chocolates that she will ooze into every nook and cranny of your cerebrum, until you won't be able to think of anything else. And if you let her take up residence there, no matter when you cut her off, no matter how hard you try to starve her, you may never, ever, get her out.

Let's say, for the purposes of this conversation, that the other woman lives in a foreign city. Let's say it is Istanbul (though it is not Istanbul). Let's say she is married to the minister of economics (although she is not married to the minister of economics). Let's say she practices a religion that does not recognize divorce. Let's say she and her husband have four children between the ages of two and ten. Let's say that when the man in your life went over to the city that is not Istanbul to visit her, the man who is not the minister of economics hired other men in trench coats to follow them around. Let's say one or another of these trench-coated men approached the man in your life in a coffee shop and told him that the price of a life in the city that is not Istanbul is one hundred dollars U.S. Let's say the man in your life told you this story with an impish grin on his face and his palms raised to the ceiling, like, What is a poor American boy in love with an unhappily married Turkish Muslim mother of four to do?

Which brings us to the man in your life. Let's say he is a painter (though he is not a painter), and let's say the Other Woman is a painter, too. Let's say they met at one of those places in Italy or New Hampshire where painters go for a month to compliment each other's paintings and gossip about other painters and after a long day of gossiping about other painters, fall together into bed. Why the painter wants to risk getting himself killed in a city that is not Istanbul for a woman who enjoys lying to her husband and her children and all of her friends and her religious co-practitioners is only one of the mysteries of this whole escapade. But then, why you have fallen in love with a man who wants to risk his life for such a woman is at least an equally compelling question.

Let's say you have known your painter for twenty years. Let's say you met at a student art show when you were both in graduate school and you had an amazing conversation about some artist who has fallen so far out of fashion in the two decades since that night that you can't be sure anymore who it was. Let's say you were attracted to each other immediately but you did not fall into bed together, and now you wonder why. Maybe it was because you were both too young and you knew you would have screwed up your relationship, and maybe fate or God or providence wanted you to wait twenty years so you would be mature enough to see that you really belonged together for the long haul. Or maybe you did not fall into bed together twenty years ago because in those days you only fell into bed with assholes and the painter was not (at least not yet) enough of an asshole to really catch your eye. Or maybe it was because the painter only liked tragic, super-thin (never skinny) women, and you have never been enough of either. Maybe you were too busy noticing the assholes at the art show, and he was too busy noticing the onelegged bulimics who had to sell themselves on the streets of Paris to put themselves through school.

In any case, let's say you were at a party ten years later (and also ten years before now) where the painter showed up unexpectedly and told you a story about the night his father died and that story made you fall in love with him for certain. Why you didn't fall into bed together that night is also a mystery because you were more or less out of your asshole phase by then, and he had already lost quite a bit of hair on the top of his head, and probably couldn't get the tragically thin women to look his way anymore. But let's say that ten years after the night of the party, your father dies and he is the very first person you want to e-mail and next thing you know, you are back in regular touch.

Let's say you and the painter plan a weekend together in San Francisco, SF MOMA and the galleries-you'll drive-and when the e-mail says I'm just a dog waiting for you to lower the tailgate, you know that after twenty long years, you and the painter are going to fall into bed together at last. But first let's say you spend two days of a three-day weekend acting like (what you are) old friends. Let's say that when you tell him that being in love with a married Muslim woman who lives five thousand miles away sounds a little self-punishing, he smiles brightly and says that he is waiting for the Other Woman's husband to die, so he can bring her and her four children to the States. When you ask how old her husband is, he says thirty-eight. When you point out to the painter that he is fifty-one, he says, Turkey is hard on people; I know I'll live longer than he will.

Let's say that you decide that what is between the painter and the married Muslim mother of four can only be about the illicit sex, and when you ask (still clinging to the safe distance of long-term flirtatious friendship) Is it about the illicit sex? the painter says not only No, but also volunteers that sex with the Other Woman is not particularly good. He goes on to say (by way of too much information) that the Other Woman doesn't let him do anything her husband doesn't do, and given the constraints of their strict religion (not to mention the fact that they dislike each other intensely), her husband doesn't do very much.

Let's say that when you finally do have sex with your painter, on the last night before you drive back to your neighboring cities, you let him do every single thing the Other Woman won't let him do, and you do several things to him that she has never even thought of. You do it for hours and hours and hours, until the front desk calls to ask if you intend to stay another night. Driving across the Bay Bridge, you stare out at the boat lifts that stand over Oakland's harbor and wonder why, instead of replaying all of the weekend's good food and great sex and long walks down city streets in the misty dark, you are rehashing every single word he said about the Other Woman. Whatever kind of sex they have, she has lodged herself firmly in the four-bedroom house of your parietal, temporal, frontal, and occipital lobes. The wrapper is off the first box of chocolates and she is making herself comfortable, changing around the furniture to suit her taste and draping her favorite scarves over your medulla oblongata. For not one moment do you consider the possibility that, in this scenario, the Other Woman is actually you.

Let's say the first post-coital e-mail is full of words like wow and wonderful, but in the third one the painter admits that he has not been able to emerge from the throes of angst regarding the Istanbul situation. Let's say that this surprises you a little because in the four years since they started sleeping together, the painter and the Other Woman have seen each other three times for a total of eleven days.

Let's say you decide that the throes of angst are possibly the most unsexy place a man can claim to be, so you ignore the throes entirely and send a suggestive e-mail inviting the painter to your favorite fireplace hotel on the Mendocino Coast. When he turns you down politely, even a little condescendingly, you go to Mendocino anyway and pick up a twenty-nine-year-old professional salmon fisherman with lots of hair, great freckles, and callused hands, and the two of you spend the whole weekend in the fireplace hotel's king-sized bed. When the painter pops back up on your e-mail a month later, apparently post-throes and wanting to see you, you wait three days, and then agree.

You have known the painter for twenty years, after all, and you convince yourself that in all that time he has to have had some therapy. Surely it will be obvious to him that you-a living, breathing, financially secure, ESPNwatching, blow job-giving (the painter calls them birthday jobs), gourmet-cooking, age-appropriate woman with blue eyes and sexy calves who is right there in his own country with her arms open wide-is far preferable to a woman who runs around dingy Turkish hotel rooms screaming I'm a motel whore, I'm a motel whore whenever the painter tries to give her a foot rub. And let's say that when the two of you finally make it to Mendocino and the painter tells you he loves you (with no prompting whatsoever from you and no reciprocation afterwards), you decide for sure that you are right.

Let's say that two weekends later, in Seattle, the painter makes a big point of telling you that he sent an e-mail to his other girlfriend in yet another exotic locale. Let's say it is Nicaragua (though it is not Nicaragua). Let's say she is the daughter of a Spanish diplomat (although she is not). This is the Other Other Woman, the other one he told you about the weekend you finally (after twenty years) fell into bed together, and frankly, you have been spending so much time thinking about Istanbul that you haven't given Managua very much thought.

Let's say that in San Francisco the painter had called the relationship with the Other Other Woman a lightbulb relationship, as if you would know what he meant. Let's say that when you looked at him blankly, he said, You know, on again, off again. Let's say he also told you that the Other Other Woman's doctor said she was too fat to get pregnant. You tried (at the time) to imagine how fat one would have to be before a Nicaraguan doctor would declare you too fat to get pregnant, and you decided that whatever it might mean, it meant that she was at least fatter than you. Also, he had reported (incredulity creeping into his voice) that the Other Other Woman told him he could do whatever he wanted with whomever he wanted when he was away from Nicaragua, as long as when he was in Nicaragua, he belonged only to her. Let's say you asked him why he didn't believe her. Let's say you asked him why men don't ever believe a goddamn thing women say.

But let's say that back in the present, in Seattle, on the fifth "date" since you fell into bed together, the painter tells you he has written a Dear Juan letter to the Nicaraguan, telling her not to wait for him. Let's say you say, I thought it was a lightbulb! Then let's say you say, Are we ready to have this conversation? Because I'm not sure we are ready to have this conversation.

Let's say when you say this you are thinking a little bit about the salmon fisherman, who you have very tentative plans to hook up with in Tobago in the spring, but mostly you are thinking about the way a conversation about the Other Other Woman is sure to lead to a conversation about the Other Woman, and since she is already half naked, watching old Doris Day films and throwing candy wrappers all over your corpus callosum and filling up all your subarachnoid space with half-read People magazines, you are pretty sure that you don't want to hear what he has to say.

Let's say he says he thinks it is time to have that conversation, and let's say he smiles kindly because he can see that you are tensed like a cat, ready to spring away. Let's say he tells you there is no comparison between you and the Other Other woman; that she, in fact, has started dating a Bolivian (let's say) and she wishes the painter, and even the painter's new girlfriend (by which you can only assume he means you), the best. Let's say you smile back, thinking about how in a perfect parallel universe the con- versation would be over at this point, but you can feel the other half of it ticking in the air like a time bomb until, finally, the painter opens his mouth and begins to speak.

Let's say the painter says it was his intention to send a similar e-mail to the Other Woman in her pathetic circumstances, in her corrupt country, in her loveless life, but when he tried, he just couldn't do it. Let's say you take a big deep breath and ask Why, and what he actually says in response to your inquiry will be the subject of every argument you and the painter have until the end of time. You are absolutely, positively certain that he said Because I love you more than the Other Other Woman, but when it comes to you and the Other woman, I feel the same way about you both. You know that this is exactly what he said, because you remember exactly what you said next: Don't ever say that to another woman as long as you live, even if you think it is what you mean.

Let's say this is not how he remembers it at all. Let's say what he says he said in answer to your Why was Out of respect for the history I have with the Other Woman, the years together we shared. And you agree that he did say that, but later, after he had called her the elephant in the room and, well, after you had started crying and screaming. You are absolutely sure that this was the order of things because you remember that you had screamed, You mean the years you didn't share, right?

Let's say that because you have spent the last twenty years in therapy, you don't say, "How dare you tell me you love me, when you love her the same exact way?" Because you have spent the last twenty years in therapy you say, Well, I hear what you are saying, but I have made myself way too vulnerable here, and I have lived too long to settle for being second to anyone, no matter how distant, how tragic, or how thin. When he says, But you aren't second and because twenty years in therapy only counts for so much, you scream in his face, I don't want to be first, either! There is still no point in the conversation when it comes anywhere near your consciousness that, technically speaking, the Other Woman is you.

What does start to become clear to you in Seattle is that all the things that make the Other Woman seem to you like such a poor, even self-destructive, choice for the painter are the very things that make her so hard for him to give up: the politically powerful husband who will only have sex in the missionary position; the kids weighing her down like Meryl Streep in Sophie's Choice. Between her impoverished country and her overbearing husband and her misogynistic religion, there is no chance her paintings will ever make their way into the larger world. The painter will never have to be jealous of the other woman's successes. The onus will never be on him to be there when she needs him. She will never bleed or fart or hurl a Vlasic dill pickle jar across a sparkling American kitchen. Her thirty-eightyear- old husband will never die. She can exist almost entirely in cyberspace and in the painter's imagination. She will remain his constant, excretionless muse.

Let's say you ask whether or not, at age fifty-one, the painter has any twinge of remorse about breaking up a family, and he will tell you in a bored voice (as though he has told you again and again, though he has not told you again and again) that the marriage has been dead for years. But if the marriage has been dead for years, you wonder, what is with the men in the trench coats? If the marriage has been dead for years, why don't she and the kids move to the States right now? Let's say he has no answer, but does say, in a fit of frustration, I can't just abandon her; she risked her life for me. And let's say you narrow your eyes and say, She didn't risk her life for you, you fucking idiot; if she risked her life for you for four straight years, she'd be dead. You are glad that you and the painter are finally, after all these years, really getting to know each other. You feel momentarily happy to live in America, a country where, for all its other shortcomings, women can say such things to the men in their lives and not be beheaded, or boiled in oil, or given thirty lashes and locked in a dingy room upstairs; where women have such an outrageous sense of entitlement that we never really see ourselves as the Other Woman. In America, the Other Woman is always somebody else.

Let's say you drive the painter to Sea-Tac Airport, even though you are only one day into a three-day weekend. Let's say you tell him to give you a call when he decides which one of you it is he loves more. Let's say a month goes by and he calls and invites you for Labor Day in San Diego. You don't ask about the Other Woman and he doesn't tell you. Let's say the weather is perfect in San Diego, but the weather has shifted inside of you. In the space between your ears, the Other Woman has gotten too big to have children. She has painted over all the windows and hung depressing art.

Let's say a few weekends later the painter says, offhandedly, that he went ahead and sent that e-mail to the Other Woman. He seems particularly pleased with himself. The two of you begin calling her Istanbul in conversation because (let's face it) neither one of you has ever been very good at pronouncing her name. You and the painter start spending more and more time together, but you are never sure if he is really excited to see you. You start to believe that if you could pick up a limp, or an undiagnosable illness, or a childhood where you walked a hundred miles with your ten brothers and sisters (all of you under the age of thirteen) to the Thai border to escape Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, then the painter might really love you. The Other Woman visits you nightly in your dreams.

Let's say one day, helping the painter look for his missing driver's license, you stumble onto a photo of him and the Other Woman in some dreary-looking Turkish suburb in front of a cement block wall. She looks nothing like the woman who has pulled up all the carpets from your cerebral platform and laid down fine, snow-white Egyptian marble. She looks nothing like the dark-eyed (if expanding) gypsy, dressed in silken cloth with mirrors that wink and baubles that rattle when she twirls over to her stash to open a new box of chocolates.

In the photo, the Other Woman is wearing Levi's knock-offs and a flannel shirt. The painter is pale and his comb-over is sticking up as if he is about to be struck by lightning. Together, they look as absolutely unhappy as two people can be.

For the entire four years they were (not) together, the Other Woman said repeatedly to the painter in her thickly accented e-mails, "We 'aff to end ziss story," and as soon as something better came along (being practical in the way men often are), end the story he did.

Let's say you look around the room and realize that, at this point, you are the only one keeping the Other Woman company. Some days you think you are beginning to prefer her company to the painter's. It is this thought that allows you to invite her out of your head (whoever she was), to clean up all the chocolate wrappers and bring in a wrecking ball to get rid of all that damn white stone.

Let's say you buy some steaks for the painter to put on the grill, you open a bottle of Sonoma red and flip through the channels looking for baseball. Let's say you slip into something silky and tell the painter if the Dodgers win tonight, he might get lucky. When he says Birthday job? you shrug your shoulders: Maybe. This is America, after all, where women have the right.

Excerpted from "The Other Woman: Twenty-one Wives, Lovers, and Others Talk Openly About Sex, Deception, Love, and Betrayal" by Victoria Zackheim. Copyright 2007 by Victoria Zackheim. Published by No part of this excerpt can be used without permission of the publisher.