How bad will tick season be this year?

When it comes to predicting how many of the ticks that cause Lyme disease will be biting this season, it's not about winter weather. Scientists say the strongest indicators are field mice and acorns.

“We base our prediction on the abundance of white-footed mice in the prior summer,” said Richard Ostfeld, a disease ecologist and distinguished senior scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. And one of the biggest factors affecting the number of mice in a given year is the amount of acorns that drop to the ground the previous year, Ostfeld said.

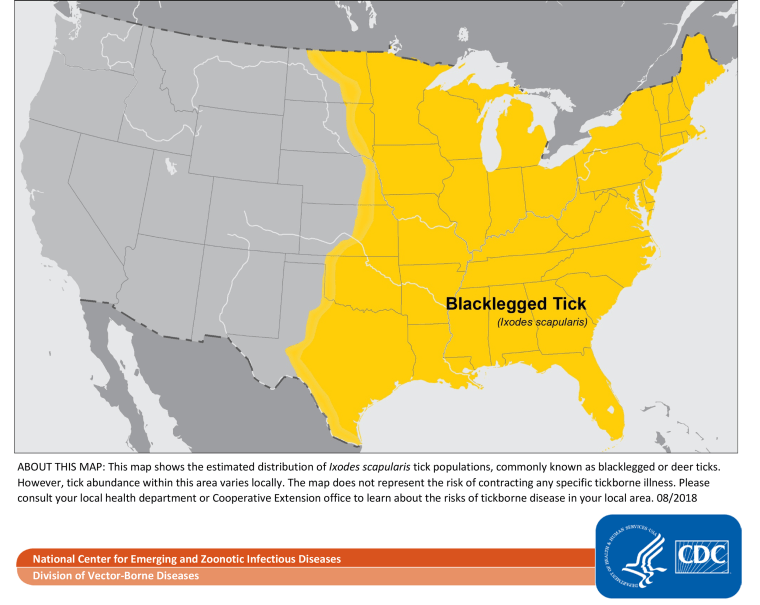

There are an estimated 90 different specifies of ticks in the U.S, including Lone star ticks which carry Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and the relative newcomer, the Asian longhorned tick, which has been expanding its range since arriving here in 2017. There haven't yet been predictions about how prevalent those ticks will be this season. Tick season typically begins when the weather warms up in the spring, and ends when temperatures drop again in the fall (though a warm weather spell in the later fall or winter can also prompt ticks to reactivate). For many people, it's the blacklegged, or deer, tick that causes most worry.

Good news for 2019?

White-footed mouse numbers were down last year, Ostfeld said. “On that basis, I expect the coming Lyme season to be average or slightly below average in terms of risk,” he said. “But I hasten to add that it’s risky every year and this should not be interpreted as meaning people should chillax and not protect themselves.”

White-footed mice are not only the preferred host for larval blacklegged ticks, but they are also natural reservoirs for the plethora of diseases those blood-sucking bugs are known for, experts say.

When larval blacklegged ticks bite these mice they can pick up as many as six different diseases, including Lyme, Powassan, babesiosis and anaplasmosis, said Alvaro Toledo, an assistant professor of entomology at Rutgers University. Those diseases will linger in the tick’s system as it morphs into a nymph, the phase in which it is most likely to bite humans, and in the process passing along whatever bacteria, viruses or protozoans the tick has in its system.

One perhaps surprising fact is that in each phase of its life, the tick bites only one animal or human. Then it moves on to the next phase.

While you might think an especially hard winter would reduce tick numbers, it makes little difference to the blacklegged tick, said James Burtis, a postdoctoral associate in the department of entomology at Cornell University.

“The blacklegged tick seems pretty resilient to the cold,” he explained. “During the winter they just burrow under leaf litter and hang out.”

What about the acorns?

For the most part, oak trees don’t shed their acorns annually. But sometimes they all drop their seeds at the same time in what is called a “masting.”

To see an example of how a masting can impact the risk of Lyme disease, you don’t have to go back too many years, said Ostfeld, whose group has been monitoring mouse populations in the Hudson River Valley for more than 25 years.

The most recent masting was in 2015, Ostfeld said.

The result was that “2016 was the biggest mouse year we’ve had in 25 years of monitoring them,” he added. “In 2017, we found the highest number of infected nymph stage ticks that we’d seen in more than a decade. And CDC statistics show that that was also a really big year for Lyme disease.”

Ostfeld cautioned that findings in the Hudson River Valley might not be valid for other areas of the country.

Ostfeld’s group is one of the few actually monitoring tick numbers. And that’s unfortunate because knowing how many ticks are around would help researchers determine whether interventions designed to reduce tick numbers are working.

One of those interventions targets deer, but doesn’t harm them.

Deer are involved in the last phase of the Lyme tick life cycle. The female ticks bite the deer and then go off to lay their eggs —3,000 of them, Toledo said.

To try to cut back on how many females get a chance to lay their eggs, researchers have been setting “4-poster systems” that have feed bins with corn for the deer to eat. While the deer are consuming the corn, brushes on the sides of the food bin coat the animals’ necks with an insecticide. The hope is that this will reduce the numbers of ticks that are able to lay eggs.

But without annual estimates of the number if ticks, it’s not possible to know whether the 4-poster systems and other methods are making a dent in the tick population, Toledo said.

So, if walking in the woods, always use a reliable bug spray.