Daphne Ischer was taking a test during her freshman year in high school when she unexpectedly got her period in class. She rushed to the bathroom but couldn't find a tampon.

"I literally just had to walk around the hallway looking for other students," the 17-year-old, now a senior at Tualatin High School in Tualatin, Oregon, told TODAY. "I asked probably 10 people before I was able to find someone with a tampon."

She returned to the classroom more than 20 minutes later, and her test score suffered as a result.

"Paper towels and toilet paper? They're provided. They're a necessity. Had I been able to just go in there and get what I needed, it wouldn't have been a problem," Ischer said.

It's a story she's told many times — to her school board as well as to state legislators at a hearing earlier this year in support of the Menstrual Dignity Act, a bill that passed largely thanks to efforts from students like Ischer, and which now requires all public schools in Oregon to provide free period products to students.

"This bill was brought up by thousands and thousands of Oregon students from every corner of the state just saying, 'This is a basic need that everyone should have,' and they felt schools should be able to provide it," Rep. Ricki Ruiz, a chief sponsor of the bill, told TODAY. "There were a lot of traumatizing stories that current and former students shared. For me and I think for some of my colleagues, it was a real eye-opener. No student should feel like that."

The law requires all public institutions of education — including elementary, middle and high schools as well as community colleges and public universities — to provide pads and tampons at no cost to students. It went into effect in July, meaning this fall is when students started noticing the new dispensers in their restrooms for the first time.

Months before the bill passed, Ischer and her peers had successfully convinced their school board to approve free period products in all Tigard-Tualatin School District schools, taking cues from students who had done the same thing in Eugene, Oregon.

A 2021 study from the nonprofit organization Period and period-proof underwear company Thinx Inc. found that nearly 1 in 4 U.S. students can't afford menstrual hygiene products, a finding executive director Michela Bedard called an "overlooked crisis."

"If we were dealing with a crisis that affected a quarter of students and had to do with food, housing or injury, this would be all over the news, we would have government programs funded around it, we have departments tackling it, but because it's such a taboo topic, it's just unaddressed," Bedard told TODAY.

"What free products in schools mean is that you don't have those uncomfortable situations like Daphne had," she added. "It also means you'll have higher student engagement. You have students that can go to school without stress. You have students that can go to school with dignity, without concern. And if they come from a home where period products are inaccessible or unaffordable, they have school to rely on for that."

A growing number of schools and institutions are providing free period products. A similar menstrual equity act has been introduced in California. Earlier this year, the governor of Washington signed a bill requiring free tampons and pads in schools. In 2020, Scotland became the first country to make period products free — for everyone, not just at schools.

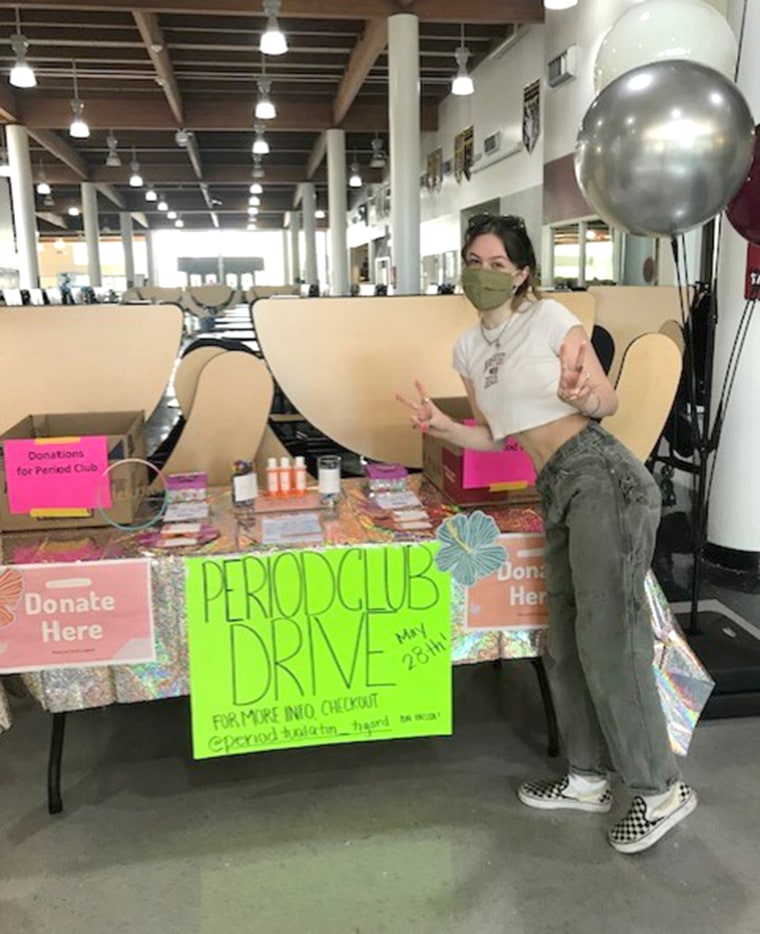

Young people have been at the forefront of much of that change. Youth activists are leading the period poverty movement, which aims to eliminate inadequate access to menstrual hygiene products as well as period-related stigma. The nonprofit organization Period has more than 325 youth-led chapters across the world. Ischer is the president of her local chapter. The group meets with school board members weekly, organizes period product drives and tries to reduce period-related shame and stigma through education.

Oct. 9 is Period Action Day, an effort by menstrual equity activists to take a stance against period poverty and stigma, which involves virtual and in-person events worldwide.

"I know that this generation — Daphne's generation — is going to solve (period poverty) in their lifetime, because of their bravery and their vulnerability in talking about an issue like this," Bedard said. "And if this generation can't solve it, nobody can."