From the moment Kelly Houlihan walks in her front door after a 12-plus-hour shift fighting the coronavirus, it will be 45 minutes before she can sit down — and hours before she can finally rest.

The 42-year-old ICU nurse at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City has a precautionary process that begins when she enters her home where her husband and two daughters live. She strips down, throwing her clothes, shoes, bra and underwear into a "COVID box" in the entryway. Then she sprints upstairs to the shower naked — hoping no one is peeking in through the window.

"I’m always trying to make sure no one is walking by," she told TODAY, laughing. "If somebody was there at the right time, they’d see me completely naked."

After a long hot shower, where she scrubs down and washes her hair twice, it's time to disinfect everything she touched before the shower — doorknobs, light switches, the shower handle.

On the occasional day where she gets home early enough that her daughters, 3-year-old Annie and 5-year-old Emma, are still up, her husband, Joe Galvano, has to wrangle them away from the front door when she arrives.

"Their instinct is to run up to me," Houlihan said. "I don't want them to hug me or touch me or come anywhere near me, and that's kind of heartbreaking."

What a 7:30 a.m. - 8 p.m. shift is really like

Houlihan commutes to New York City from her home 14 miles north in Mount Vernon, New York. She drives and it takes her about 45 minutes. Houlihan's been working overtime at Lawrence Hospital in Bronxville, New York, part of NewYork-Presbyterian, to make extra money.

Before the outbreak, she'd work one day and take a few off to be with her kids. Now, she works at least two 12-hour days in a row because it's hard "to turn (the emotions) on and off," she explained.

On her way to work, she mentally prepares: "I tell myself to expect the worst ... You’re going to have four patients, and it’s going to be a really horrible day, but you’re going to get through it ... Usually it’s better than I expect, and that makes it not so bad."

Walking into the hospital, Houlihan sees fellow health care workers coming from all blocks heading in the same direction she is.

"There’s not that many people out in the city, (but) there’s an army of people walking toward the hospital ... I get welled up every time," she said.

The day itself flies by thanks to the friendship and camaraderie of her co-workers, many of whom have come from other units, specialties and even other parts of the country.

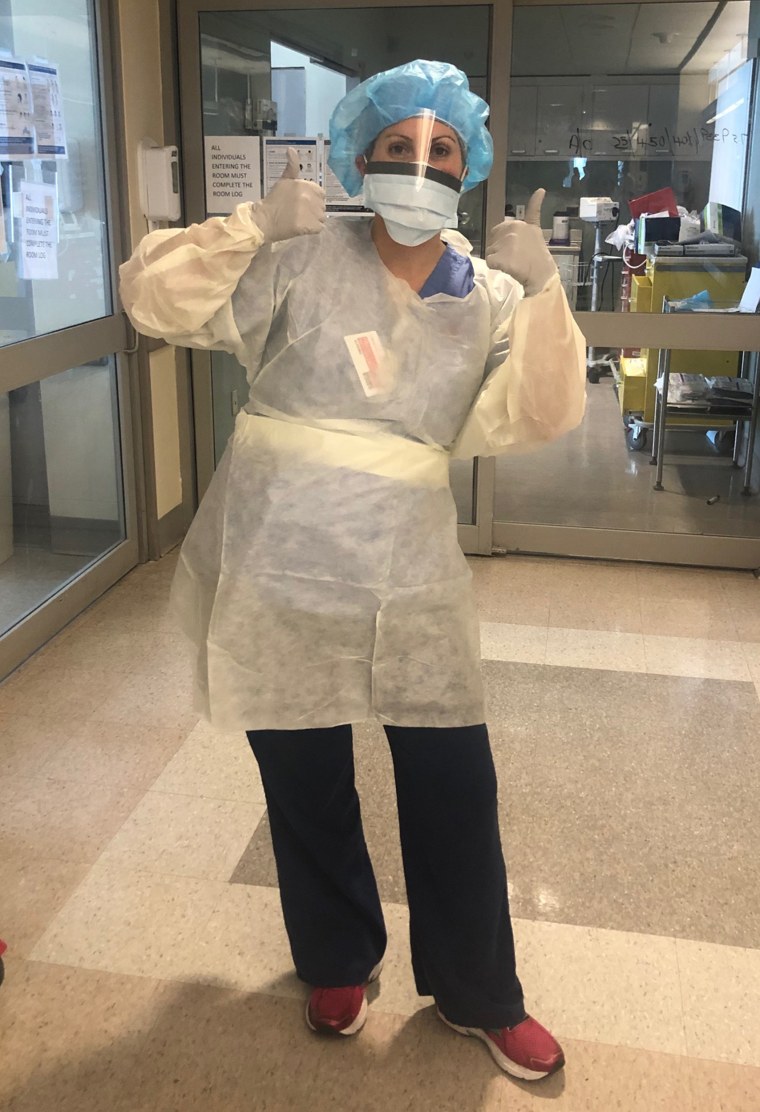

Wearing two masks and sometimes a face shield, Houlihan spends her shift delivering medication through feeding tubes, checking vitals and moving and cleaning her patients. She usually has two or three patients to care for, and most are intubated.

Being in an ICU means Houlihan sees almost exclusively the sickest of the sick. As soon as patients become stable, they're sent to a different unit and replaced with another seriously ill one. But even within the ICU, there's a spectrum. About half of her patients have been in their 60s or older, a quarter in their 30s and another quarter in their 40s to 50s.

Often patients come in, and it's clear "there's no way this person's going to make it," Houlihan said. Other times, "people seem like they're getting better but all of a sudden take a turn for the worse, and you don't know what happened ... There really was no rhyme or reason why it was one person versus the other person. It's baffling."

During her shift, if she's lucky, she'll have time to drink some water, but breaks are a rare occurrence. (NewYork-Presbyterian recently started bringing in additional nurses to work shorter shifts to address this issue.)

Before COVID-19, Houlihan could take 30 minutes to an hour for herself each shift. Lately, though, she eats her meal in under 15 minutes. Whenever possible, she sits down with a co-worker or two while someone else stays at the nurses' station to keep an eye on the patients.

"We take the masks off, joke around, talk about whatever's going on," she said. "It's 10 minutes of downtime, stuffing your face and giving the next person a chance."

Unlike many medical workers, Houlihan's feels fortunate because she's "never questioned (her) safety" due to shortages of personal protective equipment. Her team reuses N95s but never for more than three shifts, and while the supply-cabinet doors are locked, if you ask for a new gown or mask, you get it.

Around 7:30 p.m., she hands off her patients to the overnight nurse. Peering through the glass door to her patient's room, often covered in notes in dry-erase marker, she shares "every little detail" she can think of. "These people are so sick, and they can't talk to the nurse ... I've been in the car and called the unit, like, 'Oh my gosh, I forgot to tell them.' ... You don't stop thinking about it for a while."

The drive home is a ritual with her "inspirational pop music" playlist of songs like "Don't Give up on Me" by Andy Grammar and Rachel Patten's "Fight Song."

"Half the time I’m crying and just listening to music and blasting songs and singing with the windows down no matter how cold it is," she said.

When Houlihan gets home and finally climbs into bed, she can't help but question the choices she made at work that day: "What could I have done better? What could I do next time? What's happening on other units?"

She also thinks about her patients, like the father dying of COVID-19 whose daughter FaceTimed him while Houlihan held the phone. "She wanted to see his face while she contemplated an end-of-life decision," Houlihan recalled.

By the time Houlihan finally falls asleep, it's midnight or 1 a.m. By 5 or 6 a.m., she's awake with her 3-year-old, ready to start the day.

Days off are just as busy.

Houlihan's days off from the hospital are defined by her 3-year-old's preschool Zoom class and her 5-year-old's math and reading lessons, also online. Like most parents, Houlihan and her husband are struggling with home schooling. A recent email from the teacher reminded her that Emma's work was due because the end of the quarter was coming.

"We’re behind ... because I’m not home every day, and my husband’s been working," she explained.

Houlihan's own classes — she's studying to become an acute care nurse practitioner — often take a backseat, but occasionally she can organize her schedule to accommodate it. She recently worked Saturday through Monday to make time later in the week for a 12-15-page paper, case study and quiz.

There's usually an outdoor activity for the kids — chalk art in the driveway is a favorite — and plenty of screen time. With her kids at home all day and Houlihan on the front lines of a global pandemic, she's accepted that some parenting rules have to be broken.

"I'm letting them sleep in and stay up late," she said. "They’ll be in the same pajamas for like two days."

Even though laundry is piling up, in the little free time she has, Houlihan tries to learn more about new side effects and treatments for the coronavirus.

"ICU nurses ... like to be educated on what we’re doing," she explained, adding that fighting the virus is "all-consuming."

Some news stories are upsetting for her to read — as a mom and a nurse. The recent report about a 5-year-old in Michigan who died of the coronavirus was especially hard, and she has heard about protestors demanding states reopen their economies.

"I just get bothered seeing the people ... complaining, ‘I have to do this,'" she said. "Stop complaining of being bored of Netflix ... I get it. It’s boring and you’re allowed to complain, but ... I just held someone’s hand while they died. You can stay inside a little longer."

To clear her mind, Houlihan runs twice a week, a tip from her fellow nurses who've turned to exercise to destress.

"I feel like it's a washing machine for our brains," she quipped.

Houlihan may have more free time soon, however. She recently learned that her unit, formerly a cardio-thoracic ICU, will be one of the first at her hospital to go back to treating non-COVID-19 patients.

The emotions about parting with this part of her life are "mixed," she said. "There’s this sense of … everyone’s in this together. It’s kind of an amazing feeling even though it’s crazy, scary and horrible. It was just a really unique experience that ... I’m grateful for."