Phillip Bennett loved the idea of being a journalist. Organizing his thoughts in writing was a balm to him; saying what he needed to say quieted the riot in his mind.

Settling in for the writing process was a process of its own. Throughout his early 20s, the journalism major needed his mom to get him out of bed, dress him, feed him, position him in his wheelchair, and adjust the special brace he wore to support his lone typing implement — his index finger.

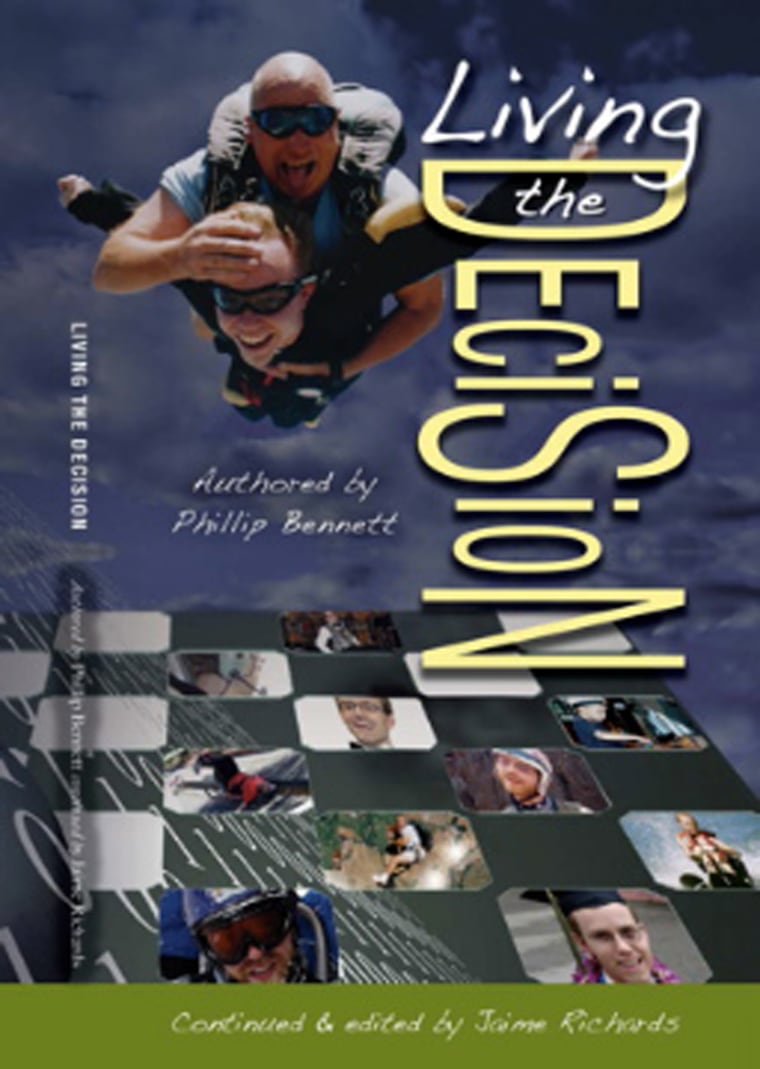

Bennett spent more than two years pecking away at his own intensely personal exposé: An account of what it’s like to live with Friedreich’s ataxia, a rare neuromuscular disease that affects roughly one in 50,000 people in the United States and has no known cure or treatment. His book, “Living the Decision: A Pocket Guide to Cramming 72 Years into 27,” just got published in December — but Bennett didn’t live long enough to see his name in print on the book cover.

“He would have loved this — seeing his book published, seeing people respond to it,” said his mother, Valerie Bennett, 54, of Fremont, Calif. “Hopefully wherever he is, he is.”

The golden years

Nothing was wrong with Phillip in his early years. In fact, he seemed almost perfect.

“He never stopped smiling,” his mother recalled. “He was an unbelievably happy kid. ... Total strangers gravitated toward him as though there were an aura about him, a light about him.”

Little Phillip loved Legos, pizza, pasta and video games like “The Legend of Zelda” that involved solving puzzles and overcoming challenges. Crazy about heights, he’d scale 30-foot trees like a fearless monkey and sway in the breeze. Teachers tended to adore him; in his first-grade year, they had him tested and identified him as gifted.

Then, out of nowhere, Phillip’s coordination waned a bit. By about age 8, he stopped showing interest in riding his bike and playing soccer.

“I thought, ‘Well, cut him some slack, he’s not a jock,’” Valerie Bennett said.

By age 9, Phillip’s handwriting got sloppier. His balance worsened. At a field day event at the end of his fourth-grade year, his mom noticed that he seemed to be struggling more than the other kids to run and crawl and throw and climb.

“I started to realize I couldn’t just say, ‘He’s not a jock,’” she said. “I thought I should probably ask about it the next time he went to the doctor.”

Phillip didn’t get sick, though, so the summer passed without a doctor’s visit. At the start of fifth grade, Phillip’s teacher pulled his mom aside and asked her what she needed to know about her new student’s special needs.

“What do you mean?” his mother asked.

“I’ve never had a student like Phillip,” the teacher explained. “What’s the story with him?”

Panicked, Phillip’s mom decided to find out. She made an appointment for Phillip to see his pediatrician, who diagnosed him on the spot. The doctor asked Phillip to leave the room with a nurse before sharing the news with his parents.

“The doctor put his hand on my hand and said, ‘I’m so sorry. He has Friedreich’s ataxia,’” Valerie Bennett recalled. “We didn’t know what it was, but we knew then that it was serious.”

Phillip’s diagnosis arrived on Oct. 4, 1994 — pre-Internet, pre-WebMD. After the appointment, Valerie drove through heavy rainfall to the public library.

There, she found and photocopied pages of information about Friedreich’s ataxia. The details she gleaned made her buckle: No treatment. No cure. Unstoppable deterioration. Wheelchair. Early death. Lucky if he makes it to age 20.

She came home, stuffed the photocopies into her husband’s hands and said, “It’s as bad as it gets.”

Phillip’s dad, Tim Bennett, read the pages over. He wondered whether his heart might stop beating in his chest.

“There was absolutely nothing good in them to grab hold of,” he recalled in his son’s book. “I felt myself spiraling from normalcy to paralysis. ... I went outside, into the rain. I climbed the ladder, cleaned the gutters, and cried.”

Faithful friends

On Oct. 5, 1994 — the day after the diagnosis — Phillip felt about the same way he did on Oct. 2, 3 and 4. He knew something critical was afoot because his parents couldn’t stop crying, but he also possessed the fantastic benefit of being 10: He could live in the now.

The one big shift he really noticed was an endless barrage of doctors’ visits. Specialists of every stripe poked at him, asked him to walk in a straight line and instructed him to try touching his nose with his index finger. (He couldn’t.) Again and again, he displayed a telltale sign of Friedreich’s ataxia: Whenever a doctor tapped his knee with a reflex hammer, nothing happened.

In spite of the annoying appointments, Phillip kept smiling as much as always and having fun playing with his little brother, Brian. He also continued excelling in school. His classmates couldn’t help but notice that Phillip’s walking and balance were off — so much so that he had to drag a hand along the wall so he wouldn’t fall over.

Phillip’s mom decided to visit his fifth-grade classroom and give a presentation about her son’s condition. The gifted students in Phillip’s class listened carefully, studied his MRI films and asked astute questions.

“Eventually,” Valerie explained, “he will have to use a wheelchair.”

Phillip attended not only fifth grade but also middle school and high school with that same group of kids — kids who took pains to include Phillip in everything.

They carried him in his wheelchair up and down staircases when there were no ramps. They made sure he attended prom and other significant dances. In high school, they even talked him into joining the track-and-field team — in his wheelchair.

Despite his lack of upper-body strength, he proudly took his place among the shot put and discus squad. He’d throw the discus 11 feet while his teammates would send it flying 120 feet.

“Never did anyone ever laugh,” his mom said.

‘Life’s short’

As Phillip’s body and speech deteriorated, he showed more and more of the fearlessness he had displayed as a little boy. Funny, candid chapters of his “Living the Decision” book are devoted to his exploits rappelling, snow skiing, waterskiing, swimming, white-water rafting and traveling to New York City so he could be in Times Square on New Year’s Eve.

A special highlight for Phillip was his first of six skydiving expeditions in July 2003. Other macho-looking guys chickened out that day. Phillip didn’t. Strapped to tandem coach Doug Behrick, Phillip tumbled out of an airplane and plummeted at speeds of 120 mph — an experience he described in his book as a “matchless rush.”

In the same chapter, Phillip speculated on the peculiar popularity of skydiving among people with Friedreich’s ataxia (FA).

“Does the struggle just to get through each day make FAers more fearless?” he wrote. “Does being captive in our wheelchairs make us hungry for the ultimate physical freedom? Are we drawn to doing something that almost no one else has done because it defines us in some way other than wheelchair-bound? Or do we just think, ‘What the hell? Life’s short. Why not go for it?’

“Probably all of those. For me, the nine thousand feet of free fall are the best seconds I know. Because during those ephemeral moments, I’m free. And strong. And brave.

“And soooo happy!”

Racing for a cure

Back in 1994, Phillip’s diagnosis with Friedreich’s ataxia seemed like a hopeless death sentence — but that’s beginning to change. Promising clinical trials are under way in the United States, Italy and elsewhere that may lead to beneficial drugs for FA patients and lengthen their life expectancies.

Much research is being spearheaded by the Pennsylvania-based Friedreich's Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA), an organization that received $200,000 in donations from Phillip and Valerie Bennett after they coordinated elaborate fund-raising dinners for the cause.

The Bennetts’ example had a profound effect on Kyle Bryant, who was diagnosed with Friedreich’s ataxia at age 17 in 1998. The diagnosis initially left him terrified.

“I knew I had it, but I had no idea how to take action against it,” said Bryant, now 31 and the founder of Ride Ataxia, FARA’s cycling program. “Phillip inspired me to get off my butt and get going.”

Through Ride Ataxia, Bryant has organized more than a dozen significant fund-raising bike rides. In 2010, he and three friends — one with FA, two without — completed a nonstop, 3,000-mile race in eight days, eight hours and 14 minutes. In all, Bryant has helped raised more than $700,000 for FA research.

“There is no doubt in my mind that we will see a treatment and a cure within my lifetime,” Bryant said. “That’s how I feel.”

‘Torn in two’

Just a month before he died, Phillip went skiing. After that thrill, he kept working on his book and started rounding up friends for his seventh skydiving trip. Then he came down with a common, albeit harsh, winter cold.

Like many FA patients, Phillip had a weakened heart muscle. His cardiologist had cautioned Phillip and his parents about it.

“He said, ‘Don’t let him get sick, don’t let him get a fever, his heart won’t take that,’” Valerie said. “In the end, his heart couldn’t handle it.”

Phillip died in the emergency room on March 2, 2011. He was 26. Left alone in the room with him, his mom sobbed uncontrollably over his body and kissed him again and again.

“I felt like I had been torn in two,” she wrote in an entry called “The Final Chapter” at the end of her son’s book. “For seventeen years we had fought Friedreich’s ataxia together, but as relentlessly as we fought it, it was a battle we could not win. For the rest of my life, I will never again feel completely whole.”

Finishing the book

Valerie Bennett never expected to have anything in common with Thelma Toole, the mom who fought valiantly to have her son John Kennedy Toole’s book “A Confederacy of Dunces” published after his death. But once her initial shock receded, Valerie knew what she needed to do.

“I could not rest — I could not consider my role as Phillip’s mother complete until his book was published,” she said.

The problem was, the book wasn’t completely finished. Jaime Richards, Phillip’s eighth-grade U.S. history teacher, had been helping Phillip compile it. Richards once joked with him, “You better not die before we finish this!” When Phillip did die, Richards was shocked — but, like Valerie, he became laser-focused on finishing the book.

“Phil had given me plenty of material,” Richards wrote in the introduction to “Living the Decision.” “Even though he wouldn’t be physically here to tell me precisely how to organize it, I’d been working with him long enough to feel confident about how he’d want the book to look.”

Richards and Phillip’s mom toiled away and ultimately decided to have the book self-published through CreateSpace. The end result is a frank account — often witty, sometimes gut-wrenching — of what any family might endure when walloped with unexpected illness. The book relays how Phillip’s diagnosis affected his parents — their marriage ended two years later — and it describes what it was like for Phillip’s younger brother Brian to grow up in the shadow of an all-consuming disease.

More than anything, though, it makes any reader want to grab some good friends, get outside and live.

“Phillip’s motto was, ‘All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us,’” Valerie said. “He had it tattooed on his bicep, and he lived that.

“None of us knows how much time we’ve got. We have to live decisively.”

To buy a copy of “Living the Decision: A Pocket Guide to Cramming 72 Years into 27,” visit Amazon.com and search for the title. All money raised from book sales will be donated to the Friedreich's Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA). To learn more about FARA and support its work, click here.

Connect with TODAY.com writer Laura T. Coffey on Facebook, follow her on Twitter or read more of her stories at LauraTCoffey.com.

More: