When Michaelene Carlton’s alarm goes off in the morning the first thing she does is try to sit up slowly and reach for a glass of water. She put the glass and an electrolyte tablet on her bedside table the night before. She drinks the water and the electrolyte and then waits for about 30 minutes.

Then she attempts to dangle her feet over the side of the bed.

If that doesn’t make her too dizzy, she’ll stand up.

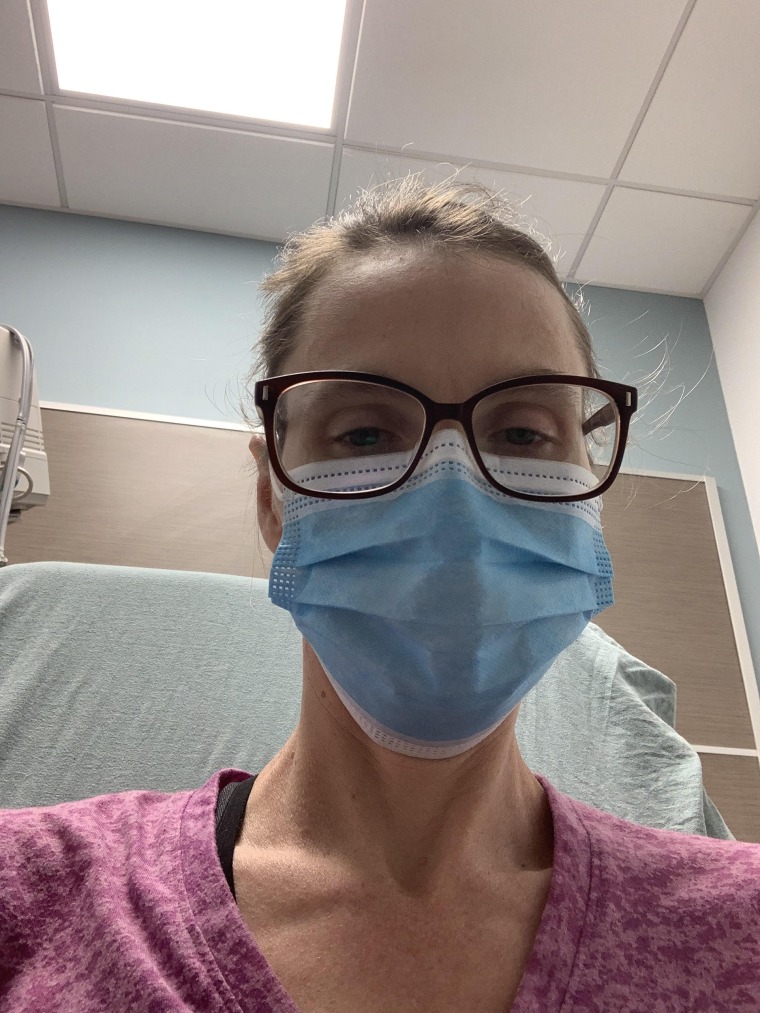

Carlton, a 47-year-old from Magnolia, Delaware, was diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) — a condition that affects the body’s ability to control its own blood flow — in May 2020, two months after being diagnosed with a mild case of COVID-19. The condition has severely limited her mobility and most of her daily activities.

Carlton said that before her COVID-19 diagnosis she had been doing yoga five times per week. She had run several half-marathons as an adult. She loved cooking dinner for her husband and their two kids, ages 17 and 14. She had been working as a paraeducator in a local special education school.

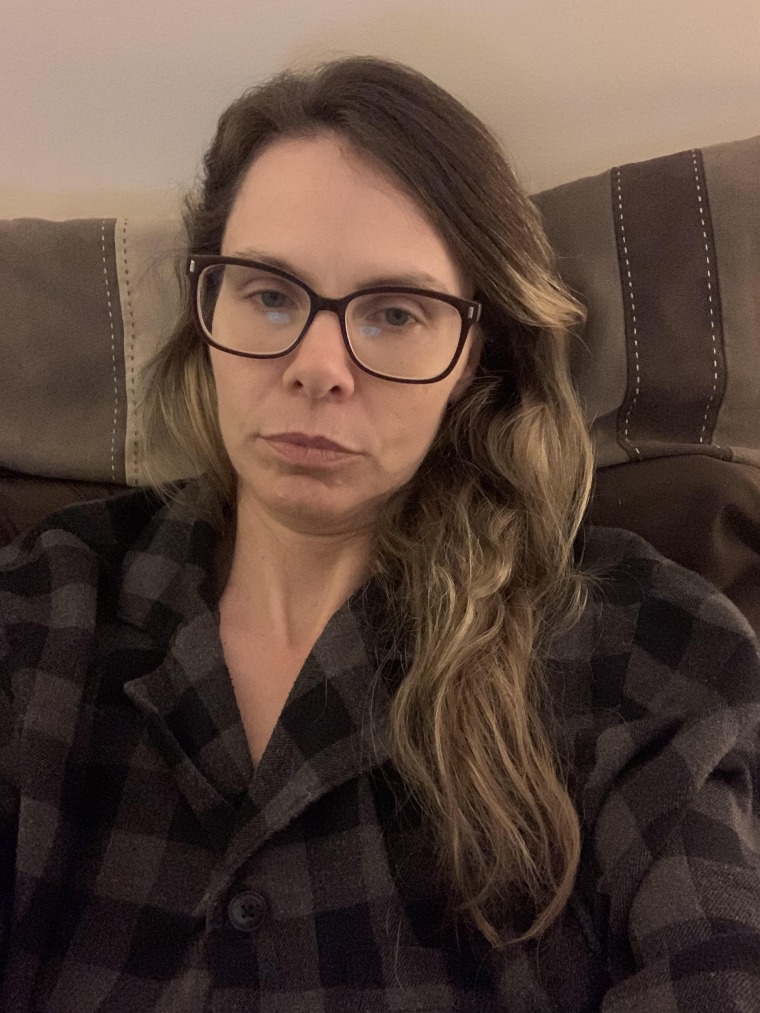

“POTS affects absolutely everything I do now,” Carlton said. “I’m not able to work. I can’t cook for my family. I can’t drive. I can’t run a vacuum.”

What is POTS?

POTS is a clinical syndrome, meaning it’s defined by a common set of symptoms. It hasn’t yet been classified as a disease because doctors don’t know exactly what causes it and what’s causing the dysfunction, explained Dr. Tae Chung, assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Johns Hopkins POTS Program.

What doctors do know is that POTS affects the autonomic nervous system, the part of the nervous system that controls things we don’t control consciously (like sweating, heart rate and gastrointestinal control). As a result of having POTS, the body loses it's ability to control blood flow or blood volume.

Blood flow regulation is something you may have never even thought of before because it’s something your body is doing for you in the background all the time. “If we stand up, our nervous system kind of squeezes or pumps the blood against gravity so we don’t collapse. When you’re exercising, blood flow to the muscles increases so our muscles can burn energy,” explained Chung, who is currently helping Carlton manage her POTS.

But in people with POTS, that regulation isn’t happening. So people with the chronic condition often experience a lot of fatigue, brain fog, exercise intolerance (or inability to exercise), discomfort and extreme heart palpitations.

From a mild case of COVID-19 to a debilitating chronic condition

Carlton went to her local emergency room three times because of extreme heart palpitations before being diagnosed with POTS.

Carlton had been diagnosed with COVID-19 in March 2020. She experienced sinus pain and headaches, but was able to manage her symptoms at home. The mild symptoms lasted for several weeks, but then they started to get better. She thought she was on the road to recovery.

I called my physician and told her: I feel like I’m dying.

“Then I just started nosediving,” Carlton said. She experienced brain fog and dizziness. She wasn’t able to concentrate. She experienced what she calls “weird electrical zaps in my head.” She couldn’t even focus enough to look at the screen on her phone. “I called my physician and told her: I feel like I’m dying,” Carlton said.

It took about two months to finally be referred to a specialist and be diagnosed with POTS. She had gone so long without an explanation as to why she was having these foreign symptoms, she said the diagnosis was, in part, a relief. “It makes you feel like you’re going crazy because you know something is going on,” she said. “It was surreal to finally have a label to put on it.”

Generally, when people are diagnosed with POTS, it’s after they’ve had a viral or bacterial infection, explained Dr. Pam Taub, a cardiologist and director of Step Family Foundation Cardiovascular Rehabilitation and Wellness Center at UC San Diego Health System.

It’s not clear yet whether patients are developing POTS after COVID-19 for some reason above and beyond why any other infections trigger POTS, or whether it’s just that we’re seeing a lot of cases of COVID-19 at once, said Taub, who treats patients with POTS and is involved in POTS research. “Clinically, the symptoms are the same, and the treatment is similar.”

Treatment can help with POTS symptoms, but daily activities are often still limited

Treatment for Carlton has included some lifestyle adjustments. She’s increased her fluid and salt intake a lot. Those steps are part of what’s known as “volume expansion therapy,” Chung explained. If you think of the blood vessels like a water balloon attached to a pump, expansion therapy helps pump water through the “balloon” to keep it (the blood vessels) from collapsing.

Carlton also started wearing compression garments, like compression stockings that cover her legs all the way up to her waist and abdominal binders, which help push blood up from the legs.

She also starting taking a beta blocker, a medication that helps lower heart rate. And she’s working with a physical therapist to improve her strength and mobility.

Exercise can be really important in POTS treatment, Taub said — but it has to be the right type of exercise. Running, cycling or other rigorous activities that require you to be upright are more likely to make POTS flare up. But strength exercises that can be done in the lying down position can be a good place to start, and people with POTS may be able to build up to other types of activity that can be done in a non-standing position, like swimming, rowing or even cycling, she said.

But exercise progression should be gradual and done under the care of a medical professional who can monitor you, Taub added.

Rarely, some patients with POTS do spontaneously get better over time or see symptoms disappear completely. But more often, people with POTS have the condition for their entire lives.

And given its apparent connection to COVID-19, there’s recently been an uptick in funding for research into POTS. Taub is currently investigating whether the drug ivabradine (a drug that slows heart rate that is not a beta blocker) can help POTS. Chung is currently involved in research looking at whether POTS might be an autoimmune disease and whether other drugs that help with autoimmune diseases can help.

“I have no other word than it is extremely difficult,” Carlton said. She said the muscle tone she’s lost in her legs is visible. The treatments she’s started are helping, but progress is very slow. She still can’t cook dinner or go on a walk with her family.

“But my new mantra is: I need to be happy and content in where I am now. I need to look forward to where I’m going,” Carlton said. “I’ll take whatever improvement I can get.”