In March 2019, Jonathan Mender, now 47, felt unwell, almost like he had a hangover. He scheduled a doctor’s appointment, but never made it there. One Friday, Mender, a dentist, started to work on a patient when he felt incredibly dizzy and needed to sit down.

“Some of his assistants took a blood pressure reading and it was off the scale,” Corey Turk, his wife, recalled. “The blood pressure monitor could (not) even read it.”

They called an ambulance and on the ride to the hospital, Mender’s face starting drooping, a characteristic of stroke. Still, calling for help immediately made a huge difference.

“They probably saved his life,” Turk said. “He probably would have been the big guy, like, ‘I think I’ll be OK. I’ll try to get home.’ When you’re 45 you think you’re invincible.”

Doctors rushed to lower his blood pressure so they could give him a clot-busting drug to treat the stroke.

“All of the things that happened with his stroke, you could see them happening, like his face drooping. He felt like he couldn’t swallow. Right before your eyes you could see him changing,” Turk said. “They finally got to a point where they gave him (the clot-busting drug) and he was lucid.”

Doctors wanted to observe Mender for 48 hours just to be safe. But then he faced complications. One of the arteries in his neck was dissected.

“Over the next day or so his brain started swelling and he seemed to be getting worse. They had to do something called a craniotomy, where they had to take a part of his skull off, to let his brain swell,” Corey said. “They had him intubated. He had a feeding tube and trach.”

He could follow commands but was mostly sedated and slept. Then he developed pneumonia and the fluid around his brain started leaking into the incision in the back of his neck. Doctors performed a surgery to remedy that.

“It would be like, “OK, we fixed this problem and now there’s this problem and now there’s this problem,” Turk explained. “He doesn’t remember anything about being in the hospital and that’s a wonderful thing.”

The stroke and its complications impacted Mender’s ability to speak so Turk does most of the talking. But the damage isn’t limited to speech.

“His stroke affects his motor coordination and balance as well as the ability to swallow and his facial muscles on the right side,” she said. “He had a lot of problems because he can’t swallow. It’s hard to eliminate (saliva),” which led to lung infections, his wife explained.

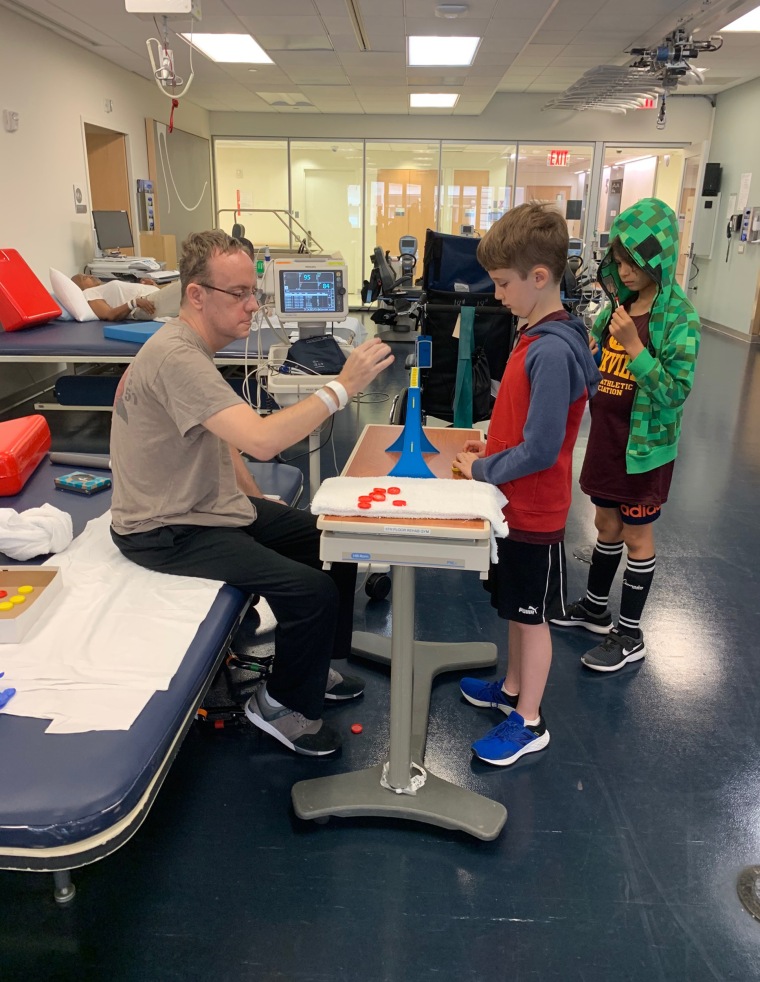

Still, he worked hard during his two months in a rehabilitation center.

“He made progress in the rehab place. His eyes were seeing double and that got better,” she said. “He’s still unable to swallow. That’s been the hardest part of recovery is getting his swallow back.”

Mender could walk with a walker and assistance with of several others. Turk attributes his success with rehabilitation to Mender's attitude.

“He doesn’t wake up in the morning and say ‘Woe is me. My life is horrible. How did this happen to me?’” she said. “He wakes up every day, he does what people tell him will help him and he doesn’t complain. He just keeps pushing forward.”

Signs of stroke

Understanding what stroke looks like is essential. Experts urge people to think of the acronym FAST:

Facial droop

Arm and limb weakness

Speech problems

Time, immediately call 911

But doctors encourage people to see a doctor regularly because there are ways to prevent high blood pressure, which can lead to stroke.

“A relationship with a primary care doctor … is one of the best ways a person can be aware of their blood pressure numbers and to get good advice on easy first steps to better control their blood pressure,” Dr. Matthew Tomey, a cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside in New York, who did not treat Mender, told TODAY. “As blood pressure goes up, the risk of heart disease and stroke go up.”

Lifestyle changes, such as eating healthy, low sodium foods and exercising, can help maintain blood pressure. But sometimes medications are also needed.

“Hypertension is often referred to as a silent killer,” Tomey said. “You can have high blood pressure for many years without being aware of symptoms or signs of high blood pressure.”

Continuing recovery

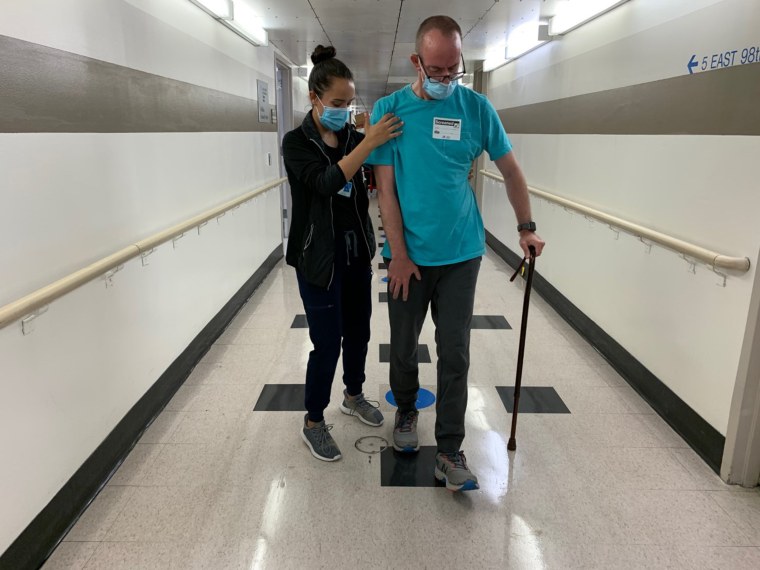

Mender told TODAY that he “wants to be more independent” and that’s why he’s in rehabilitation at Mount Sinai's Abilities Research Center. He’s been using an exoskeleton to relearn how to walk.

“For patients like Jon — who would either really need a lot of external assistance or otherwise just would blatantly not be able to do something like walking … the exoskeleton allows him to get it and start to walk with more independence,” Jenna Tosto, physical therapist at Mount Sinai’s Abilities Research Center, told TODAY. “Patients like Jon are able to have that motor support, have that physical feedback, that repetitious practice to really mimic and retrain his brain to get down to a normal walking pattern.”

Tosto is impressed by how well Mender has done with physical therapy, especially after he had to stop in-person appointments during part of the pandemic.

“Based on Jon’s current trajectory he has made astronomical gains,” she said. “I actually met Jon in the in-patient rehab setting and to just stand, not to walk, not to take a step … he required sometimes three people to assist him.”

Recently, he was able to walk just with Tosto’s help. Turk believes her husband's attitude has helped him achieve so much.

“Having that positive attitude and having that (mentality of) ‘I’m just going to keep going’ gets you so far,” Turk said. “He deserves so much credit for that.”

Related: