I have less back hair than most people, it seems, and I can thank my Neanderthal ancestors for that.

I also don’t sneeze after I eat dark chocolate — apparently there are some people who do that — and I am just the teensiest bit taller than I might otherwise have been, thanks to an inherited stretch of Homo sapiens Neanderthalensis DNA.

Genetic tests are providing endless hours of amusement for consumers this year. Most give a general geographical background that probably comes as little surprise to people who shell out the $100 or more to take the tests. One, marketed by 23andMe, takes you back even further — to Neanderthal ancestors.

“The science has been around long enough that everyone has buy-in that there is that little bit of mixture in us that ties in to Neanderthals,” said Larry Brody of the National Human Genome Research Institute, one of the National Institutes of Health.

Neanderthals thrived in Europe from 350,000 to about 40,000 years ago, but disappeared after early modern humans showed up from Africa.

Scientists were surprised when researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Germany first managed to tease DNA from Neanderthal bones in 1997 and even more surprised when it was later linked to living, modern humans.

People of European, Asian and Australasian origin all have at least some Neanderthal DNA, but not people of purely African descent. That’s because Neanderthals arose in Europe after pre-humans left the African continent and apparently never made their way back south.

The discoveries have upended our understanding of what it means to be human, and accelerated a revolution in modern attitudes towards these people who lived in Europe and mingled — obviously on very intimate levels — with modern humans.

“They are humans."

“One of the things that this report tries to do is dispel the myths around Neanderthals,” said Robin Smith, a senior product manager at 23andMe.

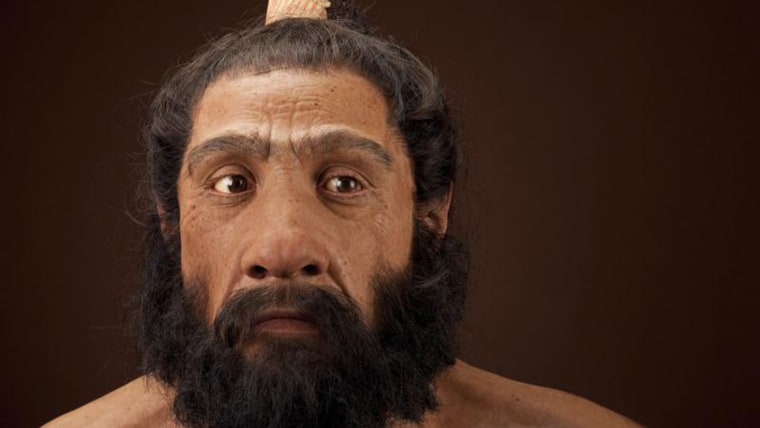

“There are these cave-men stereotypes,” Smith added. Neanderthals were often portrayed as hairy and brutish-looking, but examinations of their bones and, later, DNA shows that’s not accurate.

“They weren’t actually shorter,” Smith said. “They weren’t more or less hairy. There were some differences in terms of their skeletons — prominent brow ridges and protruding noses and whatnot — but they may not have been that different from us in reality.”

Add to this studies that show Neanderthals made cave art, wore and traded jewelry and used plants as medicine, and you get a picture of sensitive humans who were not very different from the modern Homo sapiens who took over from them.

“They are humans,” Smith said.

So what does their DNA tell us about ourselves?

Not a huge amount — yet. “This is a fun, interesting piece of information about yourself,” said Alisa Lehman, a senior product scientist at 23andMe.

“One of the Neanderthal markers will tell you things like your propensity to become addicted to smoking if you start,” said Brianna Pobiner of the Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins program.

Clearly, that did not evolve in a time of cigarettes. “Neanderthals didn’t smoke, but for some of these genetic markers, they either had a function in Neanderthals that is different from the function that we have today, or they are next to another gene that has a function today,” Pobiner said. In genetics, as in so much of life, neighborhood counts.

One that’s more important affects blood. “There is a genetic variant that leads to a high propensity for blood clotting,” Pobiner said.

“That is incredibly inconvenient for modern humans that sit at our desks all the time and don’t exercise.” It’s a leading cause of strokes and blood clots in the legs, for instance.

“But for Neanderthals living in cold areas of Europe, coming into contact with dangerous animals all the time as they were hunting them, being able to quickly clot blood when you got a cut could make the difference between life and death.”

Neanderthal DNA appears to live on in our immune systems, as well, especially when it comes to resisting infections. Neanderthal ancestors also passed along some traits for sleeping patterns, mood, and skin tone and hair color, research shows.

Pobiner said she inherited a Neanderthal gene associated with straight hair, although she says her hair is not, in fact, stick-straight.

Team members at 23andMe are crowdsourcing the information they get from customers to build up their own profile of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans.

“23andMe tests for Neanderthal ancestry at 1,436 markers scattered across the genome,” the company explains on its customer website.

“At each of these markers you can have a genetic variant that evolved in Neanderthals and came back into the human lineage when the two groups interbred. Because you inherit variants from both of your parents, you can have 0, 1, or 2 copies of the Neanderthal variant at each marker.”

My report indicates I have 294 Neanderthal variations, including, thankfully, two copies of the gene that reduces my tendency to have a hairy back.

While the 23andMe database has turned up more than 1,400 genetic changes that date back to Neanderthal times, the company has only identified four that confer traits.

“Whether you have straight or curly hair, whether you are likely to sneeze after eating dark chocolate, back hair, height — those are the four we found so far,” Smith said.

“Most of the Neanderthal DNA in our bodies, we don’t know what it does. Most of it may not do anything at all.”

While humans have about 20,000 genes that confer traits, most of our genetic code is not organized into genes. Some of it influences genes, turning them on or off and affecting genetic function.

Smith said the sneezing-after-chocolate trait turned up randomly and he has no idea if it serves any purpose. “It is a trait it affects about 3 percent of people,” he said.

“If I had a time machine, I would love to go back and see a modern human-Neanderthal interaction."

None of the traits would be visible to people looking at you, Brody said. For instance, the Neanderthal gene variation associated with height influences about 0.1 inch. At least 300 different genes affect height, Brody said.

So how did these Neanderthal genes get into modern humans?

“If I had a time machine, I would love to go back and see a modern human-Neanderthal interaction,” Pobiner said. “These were two different species yet they clearly recognized each other as similar enough that individuals mated with each other on multiple occasions over time and across space.”