When Johnnie Jae was 15, her best friend died by suicide. Then her grandmother passed away. The grief was overwhelming. Jae stopped showering and her moods swung from crying nonstop to feeling nothing. Her parents thought she was just being rebellious and dismissed her cries for help.

“No one really took the time to figure out what was going on,” Jae, now 38, an activist in Los Angeles, told TODAY.

Desperate, she talked to her guidance counselor, who was her aunt, which only caused more problems.

“We were kind of at a standstill and I didn’t know what to do," she said.

Jae, who was eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder, has continued to face numerous barriers to treatment throughout her life. She grew up in rural Oklahoma and is a member of Choctaw Nation, a federally recognized Indian tribe, where therapists and psychiatrists are not readily available.

“When it comes to our Native communities we don’t have access to mental health care. There is not always going to be a clinic or we don’t have the financial means,” she said.

Jae is not alone. Many Americans struggle to access mental health care. Sometimes it’s because there aren’t enough providers. Other times it’s because the providers are out-of-network and their insurance doesn’t cover it. And yet other times it’s because the system fails them.

Barriers to obtaining mental health care

“There are a number of things that are happening at once that make it very difficult for people to access quality care,” Azza Altiraifi, a research associate for Disability Justice Initiative at the Center for American Progress in Washington, D.C., told TODAY.

Congress passed a law in 2008 encouraging mental health parity, which means insurers are required to treat mental health the same as they would physical health, according to the National Alliance on Mental Health. If you have depression, you can see a psychiatrist or therapist as much as someone sees a cardiologist for heart disease. Yet, all insurance plans are different and some plans limit care, or are exempt from offering it. And many providers don't accept insurance because they feel they're not appropriately reimbursed for their services.

Angela Carpenter Gildner, 51, of Washington, D.C., struggled finding in-network doctors for her son Graham, 12. When he started showing symptoms of autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and sensory processing disorder, she found one in-network therapist who soon stopped accepting their insurance. Since 2012, they have paid out-of-pocket for services.

“There was one year where we took over $30,000 in medical deductions,” she told TODAY. “His actual therapy is not as bad as it used to be … For his mental health it was a little over $9,000 last year."

Dr. Cecilia Livesey, a psychiatrist at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said this complicated insurance landscape makes it challenging.

“The system is not set up to help people navigate mental health care,” she told TODAY.

And, misunderstanding about mental health, in general, provides another barrier to treatment.

“There is a lack of education about mental health,” Livesey said. “A lot of people end up in the mental health system very abruptly and at a point of crisis and it doesn’t provide good care and they are not re-engaged."

The problem with crisis care

“We are also talking about a social structure that not only stigmatizes mental illness, but it also criminalizes it,” Altiraifi said.

She said many police shootings involve a person with a mental illness. Other times, people are forced into a hospital or jailed.

Jae’s experience with what she calls “medical incarceration” after a suicide attempt in her 20s caused another crisis.

“It was very violent. It did more harm. I had my third suicide attempt after that and it had a lot to do with the way I was being treated,” she said.

Amy Baumgardner spent 15 years watching the system dehumanize her husband, Scott, 39, who had bipolar disorder. Scott followed a predictable pattern where every August he’d begin acting erratically during a manic phase that ended with immobilizing depression. Even when they felt prepared, they rarely found emergency treatment.

“He was turned away from different hospitals when he needed a medication check,” Baumgardner, 40, a teacher in Pittsburgh, told TODAY. “I had to call 911 to try to get him in.”

Sometimes Scott would end up in a psychiatric hospital, only to be released days later, or he’d be jailed. There was little follow-up. Scott rarely received the emergency treatment he needed. In May 2019, he died by suicide.

“The systems needs to be completely revamped to have more options for long-term care that are not punitive,” Baumgardner said. “There is nowhere to turn.”

New treatment models offer hope

There are programs changing how mental health care is delivered and many are community-based. Peer support, where a person with mental illness is matched with another person with a mental illness as a mentor, has shown to be effective especially for people of color and the LGBT community.

“That is a very efficient way to provide access,” Altiraifi said. “They are advocating for people in recovery. They encourage resources and skill building and skill sharing so you know how to navigate your day-to-day life. They provide community and relationship support.”

Livesey said two programs at Penn identify and treat people who need mental health care. One program places social workers in primary care physician offices. If a patient screens for depression or anxiety, they meet with the social worker who directs to them treatment.

“We identified more than 900 people who were suicidal,” she said. “That has been a huge wake-up call.”

The second program, MEND, uses mutli-disciplinary teams in hospitals to help people at risk.

“We’re proactively identifying these patients and treating them,” Livesey explained.

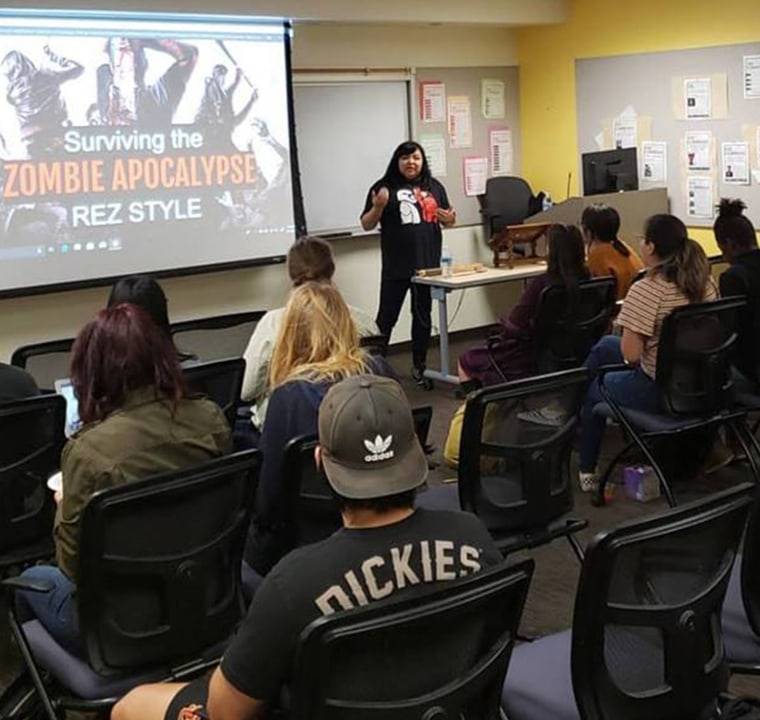

Jae works as an advocate for Native American people with mental illness and presents “Surviving the Zombie Apocalypse Rez Style,” where she talks to youth about suicide while incorporating Native American culture.

“One of the hugest barriers with youth is the fact when they tell somebody what they are going through they will tell them to stop being weak,” she said. “We treat them like they are troubled kids instead of kids who need help.”