When Isatu Alusine Jalloh gave birth, she and her husband, Alusine Jalloh, faced several big surprises. The first shock? Isatu Alusine Jalloh was carrying triplets — the couple had no idea. As they adjusted to the idea of parenting three infants at once, they faced something else unexpected. Their two daughters were conjoined by the chest and belly.

“(My wife) experienced a lot of pain because she was carrying three babies, even though we did not know it at the time,” Alusine Jalloh, 31, of Brooklyn, told TODAY via email. “After my wife gave birth, they were in the ICU.”

At the time the Jallohs were living in Freetown, Sierra Leone, and hoped that someday their daughters, Hassanatu and Hussainatu would be separated. After their son, Chernor Alpha, died of a fever, their desire to find doctors to save their daughters increased.

“They were on oxygen for the first week and even after that (they) required special care,” Alusine Jalloh said. “It was difficult to hold them and to feed them, and even changing diapers was tough.”

While caring for conjoined infants comes with loads of logistical challenges, there’s another reason why separating the babies was important — long-term survival of conjoined twins is low. According to StatPearls, only 7.5% of conjoined twins survive. Of those who are separated, 60% of them survive.

“The challenging thing is not really the technology itself,” Dr. Tomoaki Kato, chief of the division of abdominal organ transplant at NewYork Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, told TODAY. “We don’t know how it plays out in this particular case. There might be something that we don’t know may happen because it’s not really a common procedure … The most experienced (doctors) will probably see a couple of cases in their life.”

From Sierra Leone to New York

Soon after the girl’s birth, Alusine Jalloh heard from Zainab Bangurah, someone from his community that was living in the United States.

“She contacted me and asked how they were doing — I told her that they’re doing great, but that my two daughters were conjoined,” Alusine Jalloh recalled. "She said she’d try her best to help."

She reached out to her friend, Kathleen Thomas, a nurse at NewYork Presbyterian, who spoke to Kato about the case. The surgeon “championed their care.” When the girls were 3 months old, the family came to New York City to prepare for surgery. Kato and the team, which included 30 doctors, nurses and technicians prepared for the surgery. They conducted extensive imaging to understand how the girls were connected and how best to separate them.

Then the team practiced simulations trying to prepare for any complications that could occur. Even though they had a good idea of the challenges they would encounter in surgery, they also knew there could be surprises they couldn’t predict.

“Even with the heart imaging studies showing that the heart is not connected, there may be some small bridge of a heart or something like that. Then separation of the heart is needed,” Kato said. “(That) didn’t happen.”

Then they had to navigate anesthesia. Hassanatu and Hussainatu shared circulation and faced each other, making it tougher to watch their airways.

“Every single step is not simple particularly when they are connected,” Kato said. “Anesthesiologists usually work on one baby at a time ... Those children are connected, meaning they have shared circulation. So can we really do that safely in putting one to sleep sequentially?”

During the surgery on Feb. 21, 2020, doctors were able to administer anesthesia sequentially, but quickly enough that it was almost simultaneous. The virtual exercises helped the team prepare for such challenges.

The imaging indicated that the livers were connected and it appeared that splitting them might be straightforward. But still they planned for uncertainty.

“There were always some unknowns we may discover because in some cases that was reported, like a bile duct was connected or some other part of the structure was shared,” Kato said. “We’ve done a good enough imaging study prior to the time so we were fairly convinced that was not the case.”

During the surgery, the doctors noticed the girls both had “complete livers,” though separating a big swath of liver required finesse.

“The connected portion was quite wide so that cutting the connected portion of the liver requires some surgical skill,” Kato said. “There was not a major issue that we encountered during the separation procedure.”

Repositioning the liver and the hearts into Hassanatu and Hussainatu also created some difficulties. While they placed spacers in the girls to expand their skin, Hassanatu received more skin when they enclosed her heart and chest. Soon after the nine-hour surgery, Hussainatu started struggling.

“The heart became really tight so a few days after surgery, things started to escalate,” Kato said. “One of the babies was getting sicker and sicker.”

They rushed Hussainatu into surgery first for an emergency fix, but also to make sure she had enough room and skin covering her heart.

“We were able to save her in time. But that was a little bit of a scary moment,” Kato said. “It was, in retrospect, obviously, too tight.”

Two babies

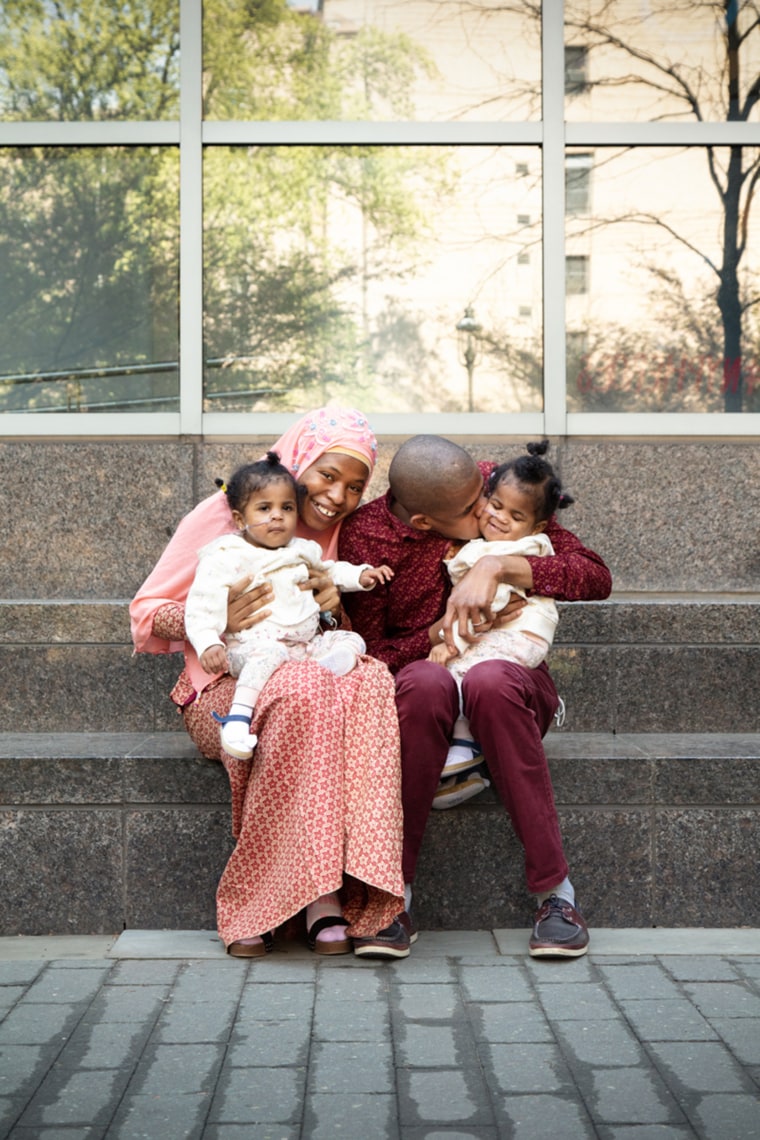

Like any siblings, Hassanatu and Hussainatu play — and fight —together. They took to it naturally after months in the hospital recovering from their surgery.

“It was so happy after the separation,” Alusine Jalloh said. “Sometimes they fight a little bit and sometimes they come together and they hug each other, they kiss each other, they play together.”

He and Isatu Alusine Jalloh relied on their faith during their daughters’ separation surgery and recovery.

“I thank God. I always give thanks and appreciation to God almighty and the entire NewYork-Presbyterian,” Alusine Jalloh said. “They did a great job for me and my family.”

Seeing his daughters “smiling and laughing” brings Alusine Jalloh and his wife great joy. Kato said from a medical standpoint, Hassanatu and Hussainatu are doing well and meeting milestones. To the Jalloh family this means renewed hope.

“They are doing great,” Alusine Jalloh said. “I want them to live a better life, like any other kids, because they are my future.”

Related: