Strangers saved a 28-year-old woman’s life when her heart suddenly stopped beating in the middle of a cross-country flight this month.

Now she and the doctor who jumped to her aid are urging everyone to learn CPR to be ready to help when a cardiac arrest strikes — an emergency that can impact more younger Americans than people realize.

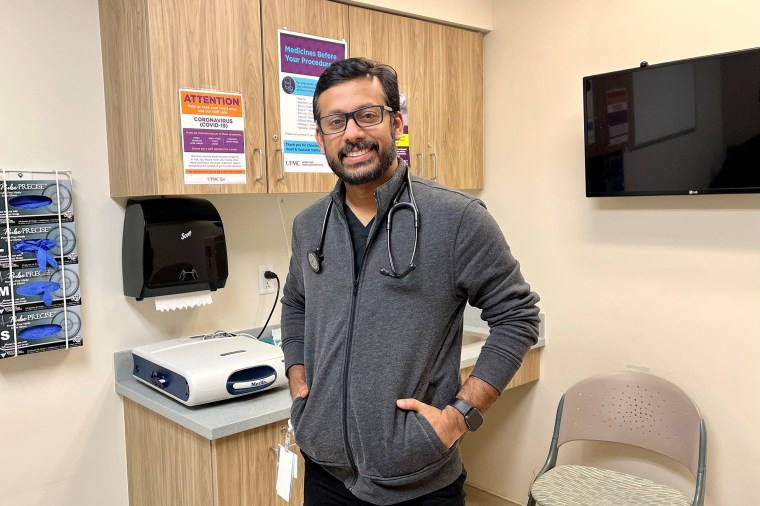

“Anyone could have done this,” Dr. Kashif Chaudhry, a cardiac electrophysiologist at UPMC in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, told TODAY about the successful mid-air resuscitation. He was one of several physicians who jumped into action when the medical crisis began. “(But) even if we were not on the plane, the outcome should have been the same,” he noted.

“It’s so crazy. You always hear about CPR your whole life… but in the back of your head, you’re like, ‘Oh, I’m not really ever going to use this,’” said Brittany Mateiro, of Woodbridge, New Jersey, the woman whose heart stopped beating. “I just can’t believe that it saved my life.”

On March 4, she was flying from Newark, New Jersey, to Phoenix, Arizona, to attend a bachelorette party. Mateiro, who works in finance for a cosmetics company, had never had any health issues before this incident, she said, describing herself as an average 28-year-old who worked out three days a week and lived a normal lifestyle.

About two hours into the flight, she decided to take a nap. It’s the last thing she remembers before the crisis.

It was at around that time Chaudhry heard screams from the back of the plane and an urgent announcement from a flight attendant asking for any doctors or nurses on board to respond to a medical emergency.

Chaudhry, who was on the flight to attend a cardiology conference in Arizona, rushed to the scene. So did his wife, Naila Shereen, who is also a physician. They found Mateiro unresponsive, slumped over in her seat, having seizure-like activity and with her eyes rolled back. Chaudhry checked for a pulse on her neck and wrist, but could find none.

CPR in the aisle

At his request, the passengers around Mateiro lifted her out of her seat and placed her in the aisle. There was still no pulse, so Chaudhry knew she was in cardiac arrest and began chest compressions. Another cardiologist on board jumped to get the automated external defibrillator from the plane’s first-aid kit. When they applied it, the device advised against a shock — likely because Mateiro’s heart beat was coming back, Chaudhry said.

After about a minute-and-a-half of CPR, Mateiro began to move. The doctor once again checked her vital signs.

“She had a great pulse. It was an amazing pulse,” he recalled. “She had no idea what was going on, she didn’t know where she was, she was completely disoriented.”

The plane was diverted to Oklahoma City, the nearest airport. As it descended, the doctors sat next to Mateiro to monitor her condition.

“I have one slight memory of looking over and seeing a woman I wasn’t familiar with holding my hand,” Mateiro recalled. It was Dr. Chaudhry’s wife.

“I was just in complete shock, I remember waiting to get into the ambulance outside the plane in a stretcher and my friends saying, ‘We’re going to the hospital,’ and I’m like, ‘What?’ I thought I was still dreaming.”

Mateiro was discharged from the Oklahoma hospital after a few hours. She decided to return home to New Jersey the next day and didn’t make it to Arizona. Two weeks later, she’s feeling fine, though a bit nervous about whether the emergency might happen again, she said.

Tests, including an MRI of the heart, will help determine what happened, with more answers expected in the coming weeks.

What is a cardiac arrest?

Cardiac arrests are more common in the elderly population, but they can strike any age group and 8% happen in people younger than 40, Chaudhry said. Given that about 1,000 Americans experience an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest every day, it means 80 of them are young — still a large number, he noted.

In a cardiac arrest, the heart’s electrical system fails, causing the organ to suddenly stop beating and unable to pump blood to the brain, lungs and other parts of the body, according to the American Heart Association. A person becomes unconscious within seconds, no longer has a pulse and stops breathing. Starved for oxygen, brain cells start dying quickly and many people who do survive a cardiac arrest end up with brain damage.

Without early intervention, up to 90% of patients die before reaching the hospital, which is why CPR from bystanders is so critical, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted.

Many people are intimidated by doing CPR because they fear they might be hurting someone who doesn't need it, Chaudhry noted.

“It is important to realize that the benefit from doing CPR far outweighs the harm that you could do someone who does not need chest compressions,” he said. “The rule is: If there’s no sign of life, you start CPR. If there’s any sign of life, you stop CPR.”

If someone is unresponsive and they don’t have a pulse, it’s best to just start chest compressions right away — if they’re not having a cardiac arrest, they will wake up, grimace, talk or push you away, Chaudhry added.

Mateiro has now signed up for a CPR class so she can be ready if someone else’s heart stops. She’s grateful to the fellow passengers who saved her life and tried to make her comfortable.

“CPR is super important and something now I’m going to be a super advocate about,” she said.