After a complicated birth, Jamell Stagg Jr.’s parents Shante and Jamell Stagg Sr. thought their son had recovered. When he never learned to hold his head up, they discovered that Jamell had an ultra-rare and fatal condition called AADC.

“It was pretty traumatic,” Shante Stagg told TODAY. “Even our neurologist was like, 'I have no idea about this. I’ve never dealt with a kid that has this.’”

While they were devastated, the family heard about a gene therapy treatment that seemingly reversed some of AADC’s worst symptoms. Suddenly, they were optimistic.

“The age limit was 5 so we tried to be patient for three years,” she said. “We had hope … There was this possibility of him being able to get this surgery.”

Missed milestones lead to answers

When Stagg gave birth to Jamell Jr. he had ingested meconium, the newborn’s first stool, and he struggled to breathe. Doctors took him to the NICU, where he received oxygen and was intubated.

“We weren’t expecting any of it,” Stagg said. “It was more a shock.”

He spent a week in the NICU and then returned home. The Staggs thought their son was developing normally until his 3-month appointment with their pediatrician.

“He wasn’t able to hold his head up and so at that time our pediatrician told us that she wanted to send him to physical therapy,” Stagg said. “At the last minute she threw in, ‘I’m going to send a referral to a neurologist because of his birth.’”

Their doctor thought Jamell had cerebral palsy or another condition that caused developmental delays. When the family saw the neurologist, Jamell underwent a lot of tests and everything looked normal. Still, the neurologist kept looking.

“We thought things would get better and we were trying to do our best at home trying to get him to start using his head,” Stagg said. “It was draining not having answers and not seeing progress.”

Finally, the doctor had a possible diagnosis.

“He’s like, ‘I think I know what it is. Before I tell you I want to tell you that there is a medication that can be useful,’” Stagg recalled. “We were like, ‘Yes!’ Hearing that there was a treatment was the best news.”

The neurologist suspected that Jamell had AADC and the tests confirmed it. AADC is also known as aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency and it occurs when a gene mutation makes it tough for the brain to produce dopamine and serotonin.

“These two chemicals are very important in the brain and (help) us control every movement, but also for cognition,” Dr. Krystof Bankiewicz, professor of neurological surgery at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, told TODAY. “Children are being born with that mutation and … cannot produce these chemicals.”

The approximately 200 children with AACD worldwide do not meet milestones, such as holding up their heads, rolling, crawling or walking. They have problems regulating their glucose, develop dystonia, struggle to breathe, inhale their secretions, experience cardiac problems and experience long-lasting seizures called oculogyric crises. Most children with AADC die in their teens.

When the Stagg family visited the medical geneticist, they learned that AADC treatments don’t always work. Still, they put Jamell on several drug combinations to help him. But he didn’t improve.

“It was a very stressful time, trying to find the right combination of them, and none of them worked,” Stagg said. “We tried to navigate life the best we could and tried to give him the best life.”

Then Stagg joined a support group of parents with children with AADC and learned about the gene therapy. That gave her hope. As they waited for him to age into it, Jamell faced health complications.

“He started developing a curve in his spine because of his low (muscle) tone and he really had a big problem with hypoglycemia,” she said.

When he was 3, Stagg found him unresponsive and soaked in sweat. She took him to the emergency room where doctors learned Jamell’s blood sugar was below 10 and they had to give him an IV to stabilize him. After that he had to get a gastrostomy tube for consistent nutrition to help. While that helped his glucose, he still had hours-long seizures where he stiffened, choked on his secretions and threw up. There was little his parents could do to ease Jamell's suffering

“It lasts six-plus hours every three days,” Shante Stagg said. “There was nothing we could do to get him out of it.”

'Nothing short of a miracle'

About 10 months ago, Jamell, who will turn 7 in October, had the targeted gene therapy surgery in Columbus with the team who had performed this surgery on others with AADC. Their research on seven such procedures was recently published in Nature Communication.

“I gave (the gene therapy) deep within the brain where these cells actually reside to really give them a normal copy of the lost enzyme,” Bankiewicz said. “The results were staggering, very significant. The reason for that was the patients for the first time in their lives were able to make dopamine in the brain.”

This one-time therapy should allow the children to continue to make dopamine and many have regained skills.

“The normal function of the brain resumes and they really develop very quickly,” Bankiewicz said. “They’re meeting a lot of developments they would have never reached otherwise.”

The first thing the Staggs noticed is that Jamell’s seizures stopped. He had one a month after his surgery and then no more. Then he started sitting up.

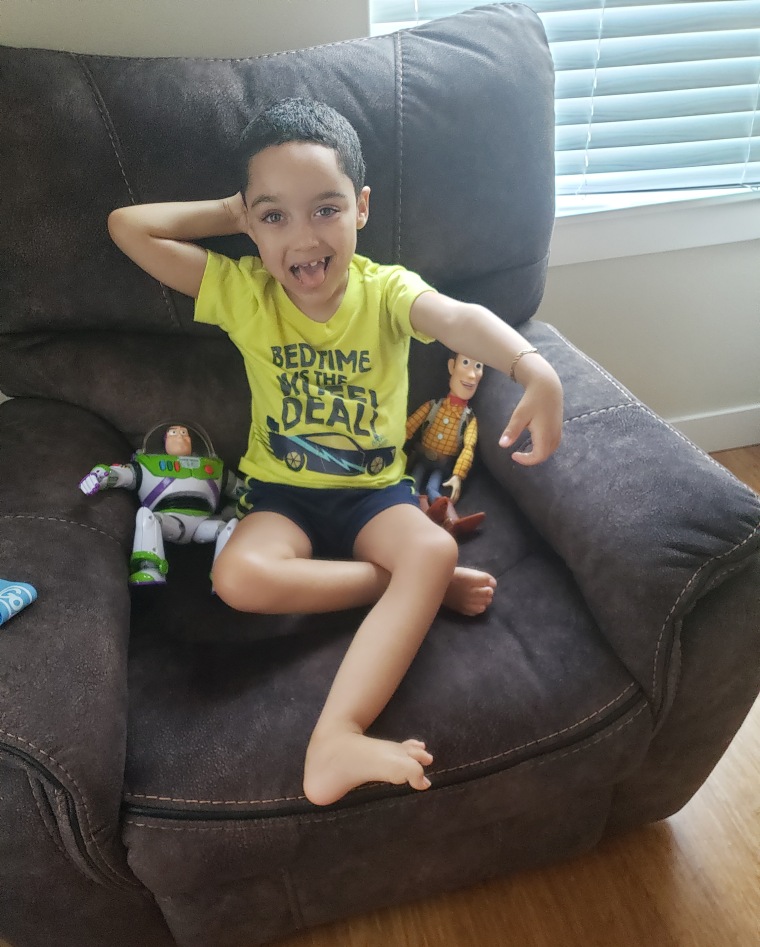

“He can play with toys. He can reach out and grab things if you’re holding something in front of him. His awareness is shocking to see,” Stagg said. “He rides horses, he does hippotherapy (physical therapy with horses) every week.”

While Stagg said that Jamell was always a happy, sweet child who loved to visit the zoo, they feel overjoyed to see him play. They love that he sits up to watch movies, clutching his toys. They catch him smiling at himself in the mirror and feel thrilled by his progress.

“It is so exciting to see our child do typical things,” she said. “This is nothing short of a miracle."