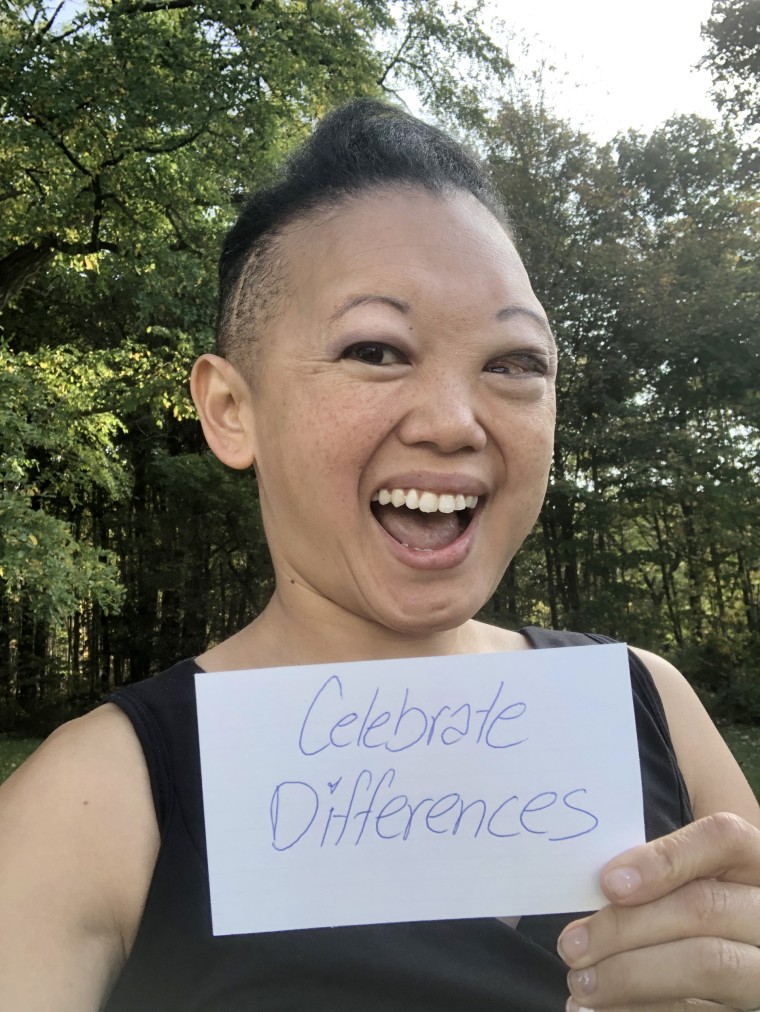

Sora Iriye, 39, is a circus artist and co-founder of CirqOvation, a circus entertainment company in LaFayette, New York. Born with craniofacial differences, she’s an advocate for face equality as a human rights issue. She shared her story with TODAY for Craniofacial Acceptance Month, which is observed in September.

I was born with lymphatic malformations and venous malformations that affected the left side of my face. There is no known cause or cure.

My left cheek and neck were very swollen as a kid, and my left eye was pretty much swollen shut. The venous malformations caused chronic tearing and bleeding. Surgery saved my eyesight — it reduced the swelling enough so that my eye could open.

My first surgery was when I was 3 years old. That same year, I started dance lessons when my mom enrolled me in ballet.

Dance gave me the ability to feel seen, beautiful and valid. My mom said, “When you’re on stage, no one notices your face,” and what I think she meant was, “When you’re on stage, people can look past your difference and see you for who you are.” Now, I don’t want people to look past my difference. I want people to see my humanity, not despite my face, but because of everything I am.

Growing up in Arizona, my family was incredibly supportive and I actually had a lot of confidence as a kid. But I had to push so hard to have my life validated by the rest of society. I had to prove myself every step of the way.

It’s a daily experience for people with facial differences to get intrusive questions like, “What happened to your face?” or “What’s wrong with your face?” — that’s very common, which I think is so messed up. I see curiosity or fear when strangers are winding up to ask these questions. I also see pity a lot.

For me, it becomes more complicated because I’m also Japanese-American, so there is always the sense of being a perpetual outsider. I get to play the game of race or face: Is someone going to ask me about my face today or are people going to ask, “Where are you from?”

I’ve had nine surgeries, which is a low number for the facial differences/disfigurement community. Some surgeries were medically necessary; others aimed to create a more “typical” face. I am forever grateful to my family for trying to give me every chance at a “normal” life. But what I would have really wanted was for that “normal” life to be a result of a culture where typical faces were not a requirement for full participation in society.

When I was in college, I decided I didn’t want to seek more treatment. I just wanted to not be in the hospital. My left eye has worse vision than my right and I still have pain at night from sleeping or any time I experience a lot of stress. I didn’t realize until a couple years ago that I was constantly in pain because I’ve lived with it all my life.

I graduated from college magna cum laude. But I had always been a dancer and in college, I discovered aerial arts — I had taken a couple of aerial silks classes and I was working on dance trapeze.

I took a year off after graduation and pursued a different path. I started performing aerial arts with a company in Cleveland, Ohio, and decided that I wanted to do this full time. I went to circus school in the UK to finish building my skills.

My husband and I have traveled all over the world doing what we do and then founded our own circus entertainment company to bring other performers into the fold.

Mental health struggles are extremely high in the facial difference/disfigurement community, as are hate crimes against us, job discrimination and social exile.

Defining face equality as its own human rights issue is so paramount right now because in this society, our faces have become a form of social validation, almost a form of currency. I want society to lower its defensiveness against people who look different. It is such an arbitrary means of finding value in a person.

Craniofacial Acceptance Month is so important. To advance towards equity for the facial difference/disfigurement community, we need to shift the cultural conversation that surrounds us — and that means changing perceptions.

Instead of adhering to the medical model of disability — that we need to be fixed; or the moral model — that we should be hidden away and exiled because our faces are the result of some moral failing by us or by our families; we need to amplify the social model of disability, which states there is nothing wrong with us.

I want people to examine their deeply held beliefs about what they think is beautiful and worthy of adoration and ask why? Why do we value people less based solely upon what they look like?

The next time you see someone with a difference, take a moment before asking intrusive questions. Children are curious, so I’m speaking more about adults.

You can help eliminate your intrinsic bias by just taking a beat to recognize a person’s humanity — not through a lens of pity, but by recognizing them as someone who is probably more similar than different from yourself.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.