Editor's note: Cai Emmons died on Jan. 2, 2023, almost two years after being diagnosed with ALS. "Remember her with joy," read a note shared on her Twitter page. This is an essay she wrote for TODAY.com months before her death about how she finds humor in even the darkest moments.

I imagine most people, like me, receive a fatal diagnosis with surprise. We all know intellectually that we will die, but no one really feels death as a certainty. We tend to live as if we’re immortal, feeling our expiration date as an unreality we can push indefinitely into the future. Maybe our lives will be the exception to human life — maybe we’ll be the first immortal. I know that is how I lived, with an unconscious belief in immortality, until my ALS diagnosis in February 2021. There is currently no cure for ALS and the mean survival time is two to five years. And yet, maybe I still harbor the notion that I’ll outwit the disease and live into my nineties as my mother and grandmother did.

From the day of my diagnosis, humor seemed to pop up out of nowhere. When we stopped at a mall on the way home from the doctor’s, seeking retail distraction from the magnitude of what we’d just learned, a clerk asked how my day was going. I had to work hard to keep from collapsing in laughter. “Fine,” I said, refraining from adding, “except for the fatal diagnosis.”

A clerk asked how my day was going. I had to work hard to keep from collapsing in laughter. “Fine,” I said, refraining from adding, “except for the fatal diagnosis.”

I have always been a provocateur. Maybe it comes from being a middle child. I loved making mystery phone calls as a kid, and well into adulthood I made it my mission to do April Fool’s jokes: Vaseline on the toilet seat or peanut butter on the phone receiver. And I have been known to skinny-dip in situations that shocked others. I can’t say exactly what has drawn me to such behavior, only that I like rocking the boat, pushing boundaries to get a rise out of people.

This is part of what has drawn me to being a writer. On the page one can say anything. In fact, it is a writer’s job to say aloud what others are trying to ignore; it is a writer’s duty to surprise and provoke.

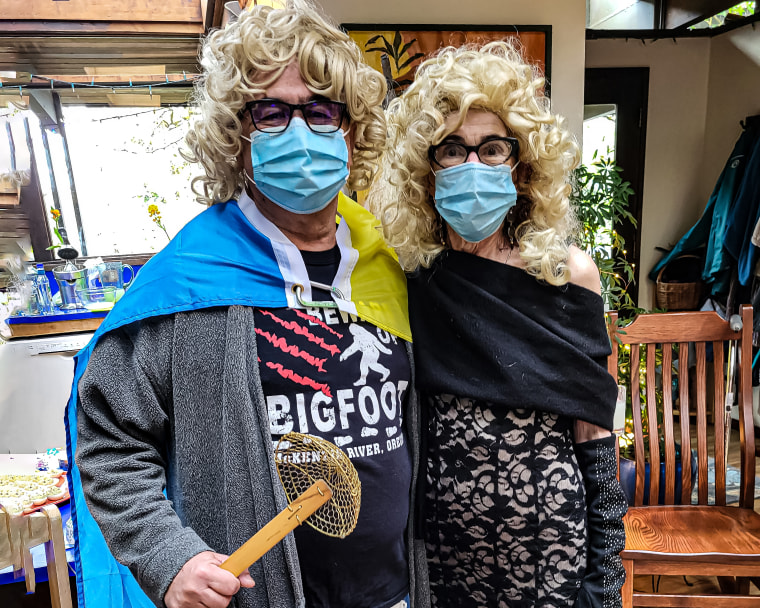

What I have discovered in the last year and a half is that death is a topic that most people would rather not discuss — and so, being who I am, I often bring it up. “After I’m dead … ” I have taken to saying not infrequently, and my statement is met with awkward chuckling. Some people push back: “Oh, Cai, you’re not dying,” they say emphatically, and we all laugh. I feel this general cultural death avoidance in the way some people visit me, timid and afraid of saying something wrong, but wanting to see what dying looks like, believing I have access to some occult knowledge. I try to be straightforward, showing them my crooked fingers, my feeding tube, cracking jokes, anything to make sure we don’t brush the subject under the table.

I can’t help myself. I find my weakening body not only a subject of fascination, but I find it funny. I am not happy about the prospect of losing the use of my hands, but when I have to ask my husband for help with buttons and zippers, and he tends to me like a child, we both laugh. When my feeding tube came out, and there was an open hole in my belly, we both became weak with laughter. When I fell face forward in the lobby of a doctor’s office, a slew of patients watching, we laughed then, too. And when, to prevent my mouth from drying out at night, we taped it closed with duct tape for the first time, we couldn’t control our hysterics. Another big laugh came when we learned that the “death with dignity” potion can be administered rectally. That didn’t sound to us dignified at all, and laughter ensued.

I often feel playful and antic these days, gesturing with my own invented sign language or squealing at high volume, because that is the only sound I can make. ... Though I can't speak, I still have a zest for life.

I often feel playful and antic these days, gesturing with my own invented sign language or squealing at high volume, because that is the only sound I can make. Doing these things makes me feel alive, and it reminds others that I’m present and, though I can’t speak, I still have a zest for life. A friend of mine — someone with whom I’ve taken to exchanging punches and friendly insults — commented that I’m approaching death as Charlie Chaplin would. His humor springs from dire situations: poverty, pain, hunger, loss. She referred me to the boxing scene in “City Lights” where Chaplin, totally ill-equipped to fight, undermines the contest with his antics. The comparison is apt — when we are helpless to change things, we may as well find the humor in them and laugh.

My squealing and gesturing and pratfalls are also, like Chaplin’s, a form of provocation. I want to gently destabilize people by reminding them that death happens no matter what — it is nonnegotiable. And even though we see death on the news daily from wars and shootings, it’s hard to see it operating in our own lives.

I think, however, that a subliminal awareness of death prompts so many of the things we do in life. We try to eat right, exercise enough, take vitamins, do yoga and meditate so we can forestall death, or at least prolong life. If we produce offspring or consequential work, maybe we will create a legacy that outlasts us. But the joke is we’re all going to die — and eventually be forgotten despite the things we might do to defy death. Sometime in the last eighteen months, it has become my mission to bring death into my conversations and hopefully show those around me that it needn’t be so bad.

Mexican culture seems to get this, accepting death as an inseparable part of life. Humor is an integral part of that. The iconography of Day of the Dead skeletons grinning and dancing may seem macabre to most Americans, but it’s a way of befriending death and making it less scary.

George Orwell said of humor: “A thing is funny when — in some way that is not actually offensive or frightening — it upsets the established order. Every joke is a tiny revolution.” My life seems to have become a tiny revolution, devoted to disturbing the established order. I move in the world among friends and strangers as a person who is both living and dying, doing both with enthusiasm. And when death finally comes for me — and of course I still don’t really believe it will — I hope that, in whatever afterlife I find myself, I’ll be like those Mexican skeletons, grinning and dancing.