As James Fisher awaited experimental brain surgery he underwent recently, he wondered whether it will be the treatment that finally helps him get his addiction under control.

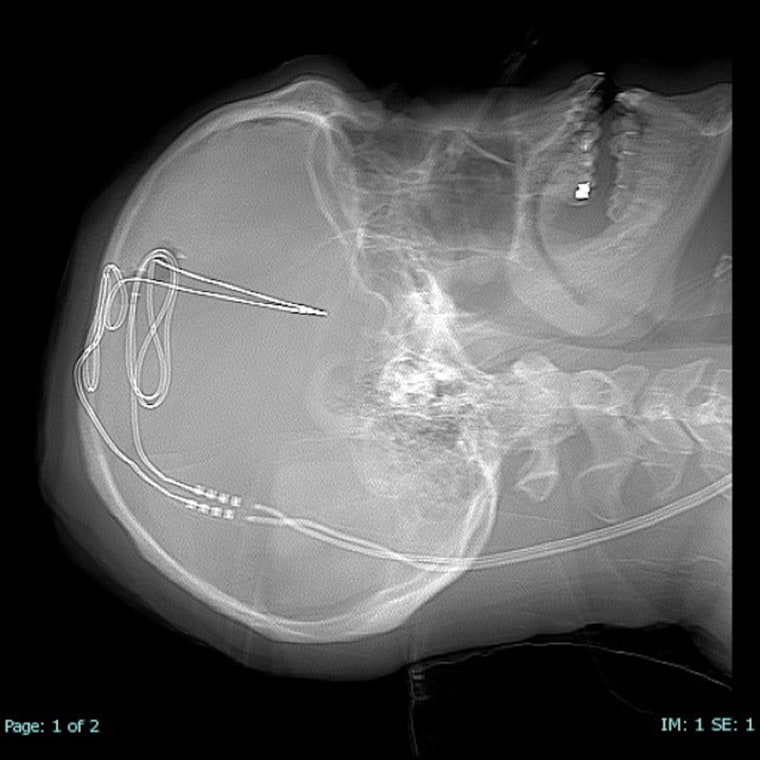

The tiny electrodes surgeons implanted in the reward center of his brain are designed to carry electrical stimulation that could, in theory, help drown out the constant craving he feels for benzodiazepines, his drug of choice.

Fisher, 36, who lives in West Virginia, is the third patient enrolled in a clinical trial being conducted at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute. To be included in the study, which uses a technique called deep brain stimulation, patients must have gone through numerous rehabilitation efforts that didn't work and suffered multiple overdoses.

At first, Fisher, an addict since high school, easily found doctors willing to write prescriptions for his social anxiety. When that stopped working, he began buying from friends and eventually started stealing from strangers to get the money to pay for drugs. Initially it was just "benzos," but later he moved on to prescription opioids and then heroin.

After four nearly fatal overdoses, he had jumped at the chance to participate in the trial.

“I don’t want to die,” Fisher told NBC News before the surgery. “I don’t want to live that miserable life of being sober and still wanting something and not being able to get it.”

As part of an NBC News series, "One Nation Overdosed," "Nightly News with Lester Holt" was given access to West Virginia University’s experimental trial as surgeons implanted wires in Fisher's brain to treat his severe opioid use disorder.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been used successfully for decades to treat symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Doctors at the Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute developed the technique for worst-case drug addiction on the theory that targeting one of the brain’s reward centers — the nucleus accumbens — with tiny sparks of electricity could quiet powerful cravings, allowing the brain regions involved in judgment and decision-making to be heard, said principal investigator Dr. Ali Rezai, executive chair of the institute in Morgantown.

Drugs such as benzodiazepines and opioids hijack the reward system and once users are exposed, they need more and more of the substances to get the rush of the feel-good neurotransmitter dopamine.

“Our hypothesis was that by using the DBS in this part of the brain, we would essentially be normalizing the dopamine levels,” Rezai said. “In addiction, the rewards part of the brain releases dopamine when the drug is taken and people feel good. And then they want more next time to get to the same feeling.”

For Parkinson’s patients, electrodes are implanted in the parts of the brain involved in movement. In the addiction trial, the electrodes are implanted in a different part of the brain, an area that evolved to reward behaviors that keep the species going, such as seeking food and sex. Dopamine is released when those goals are accomplished, as well as at times when people are experiencing natural beauty, such as a particularly colorful sunset or an emotive piece of music.

When the surgery to implant the electrodes is complete, doctors switch on the deep brain stimulation device. For Fisher, the results were immediate and startling. The depression, anxiety and irritability are gone, replaced by a feeling of calm and comfort, like “a warm blanket.”

“It’s like night and day,” he said.

Fisher's surgery was at the end of July. After four weeks, he told NBC News he feels “fantastic” with no craving to use drugs.

Two months later, he is still sober.

“I’m willing to do what it takes to get my brain back to normal,” Fisher said. “I hope that I can get back to that period before I started using benzos. Just being naturally happy — enjoying music again, enjoying food again, enjoying seeing a smile on somebody’s face.”

The initial phase of the trial, which began with the first patient in 2019, is designed to test the safety of the treatment and will eventually include four people with severe substance use disorders. A second phase with 10 patients will test how well it works in keeping people off drugs.

The need for additional treatments for opioid addiction is urgent. In 2020, during the pandemic, drug overdose deaths spiked to record levels of more than 93,000, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, were responsible for 60 percent of the deaths.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, there were 18.9 million people ages 12 or older in 2019 with a substance use disorder and 16.3 million misusing prescription drugs.

Based on the experience of Gerod Buckhalter, the first patient to have the surgery at the institute, Fisher’s chances of long-lasting sobriety are good.

Buckhalter, 35, became addicted to prescription opioids after a shoulder injury when he was 15. Despite numerous stints in rehab and scary overdoses, he wasn’t able to shake his addiction. He immediately signed on when he was offered a chance to be the first patient in the trial.

Once the electrodes were implanted, the researchers turned on the device. The effect was dramatic.

“I didn’t find joy in living,” Buckhalter recalled. “When they turned it on, of course, I didn’t know what was going to happen in the future, but at that time I knew if I could continue to feel the way that I was feeling right then, that I would be OK.”

He says he hasn’t used even once in two years. He still goes to therapy and takes Suboxone, a compound medication designed to help with opioid addiction. But staying away from opioids is a lot easier after the surgery.

Buckhalter's recovery from the 2019 brain stimulation procedure was first chronicled by The Washington Post in June.

Experts caution that the results are preliminary and not a guaranteed cure. Of the three initial patients, one relapsed and is no longer in the trial. Even if the institute's trial shows that it can help some untreatable addicts, broader use is still years away.

“There is a lot of research where there have been positive findings initially and then they don’t prove to be that reproducible,” said Dr. W. Jeffrey Elias, a professor of neurological surgery at the University of Virginia Brain Institute. Even so, he says the concept and early findings are exciting.

“We are understanding more and more about the brain circuitry, especially with reward and addiction issues, and so we have very precise tools to target the brain,” he said.

Dr. Ausaf Bari, an assistant professor and director of functional and restorative neurosurgery at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, compares the device to a pacemaker for the heart.

“One of the things people are trying to use DBS for is to specifically change the brain circuits involved in craving and relapse,” he said. “Just like a pacemaker treats abnormal rhythms of the heart, we can use DBS to fix abnormal rhythms in the brain.”

In future studies, researchers may have to individualize the exact spots they use DBS to target, Bari said. Sparking different parts of the brain may yield different responses. Until researchers and patients try it, they won’t know how to get the most effective response, he said.

Related: