As Christal Love was taking off her bra, she felt something. At the time, back in 2016, she was 39 and hadn’t yet received her first mammogram. She didn’t think it could be cancer.

“I was like, ‘Oh wow, what’s that? I felt the lump. I really didn’t think anything of it,” Love, 46, of Perris, California, told TODAY. “I discovered it just casually one day. I didn’t have any symptoms.”

But after a doctor examined her, she underwent a mammogram and ultrasound and learned she had breast cancer. She felt stunned.

“I’m zoned out because I’m trying to remember some words that they’re telling me so I can Google this,” Love recalled. “I’m like, they don’t know what they’re talking about. And I’m not in denial, but I am kind of like, ‘This can’t be real.’”

A lump ‘the size of a golf ball’

After first finding the lump, Love forgot about it. When she visited Planned Parenthood to get a new prescription for birth control, she mentioned it, and the tone of appointment changed.

“She was like, ‘Well, if you have a lump in your breast, I can’t give you birth control.’ And I’m kind of like, ‘Why not?’” Love said. “She examines me. … She was like, ‘It is rather large, the size of a golf ball.’” The provider at Planned Parenthood encouraged Love to get a mammogram and ultrasound. Love first returned to her primary care doctor who examined her and urged her to get an appointment for images immediately. The scans revealed that Love had breast cancer that had metastasized into her lymph nodes.

“The doctor tells me I ended up having stage 3, possibly stage 4 cancer,” Love said. “My jaw literally dropped because I’m still thinking that this isn’t me. This is a dream.”

Love received chemotherapy for six months to try to shrink the tumors, but it wasn't working. What’s more, she experienced severe side effects from the treatment.

“One day, I was going to a family party, and I literally couldn’t walk,” she said. “I ended up leaning up against my cousin’s garage because I couldn’t breathe. I didn’t know what was wrong.”

Love had to go to the hospital, where she stayed for five days, but she said her doctor dismissed her symptoms as unrelated to the cancer treatment. She later learned that chemotherapy led to blood clots in her lungs, causing the shortness of breath, and she has neuropathy, a form of nerve damage that causes weakness, numbness and pain in her hands and feet, that continues today.

She felt like her original doctor didn’t care about her side effects and how they impacted her quality of life. Frustrated, she decided to get treatment at cancer treatment and research center City of Hope. The closest location was 60 miles away from where she lived.

“I realized that this (doctor) did not care about my life,” she said. “That’s when I was like, ‘OK, let me see if this referral is still good.’”

She met her new doctors on March 1, 2017, and had a mastectomy on her right breast by March 27. The surgery “was a walk in the park,” but coping with the loss of her breast felt tough at times.

“Imagine going with one breast for a year,” Love said. “That’s the part I really had a hard time with because when you think of a woman you think of hair, you think of breasts. I know that might sound superficial.”

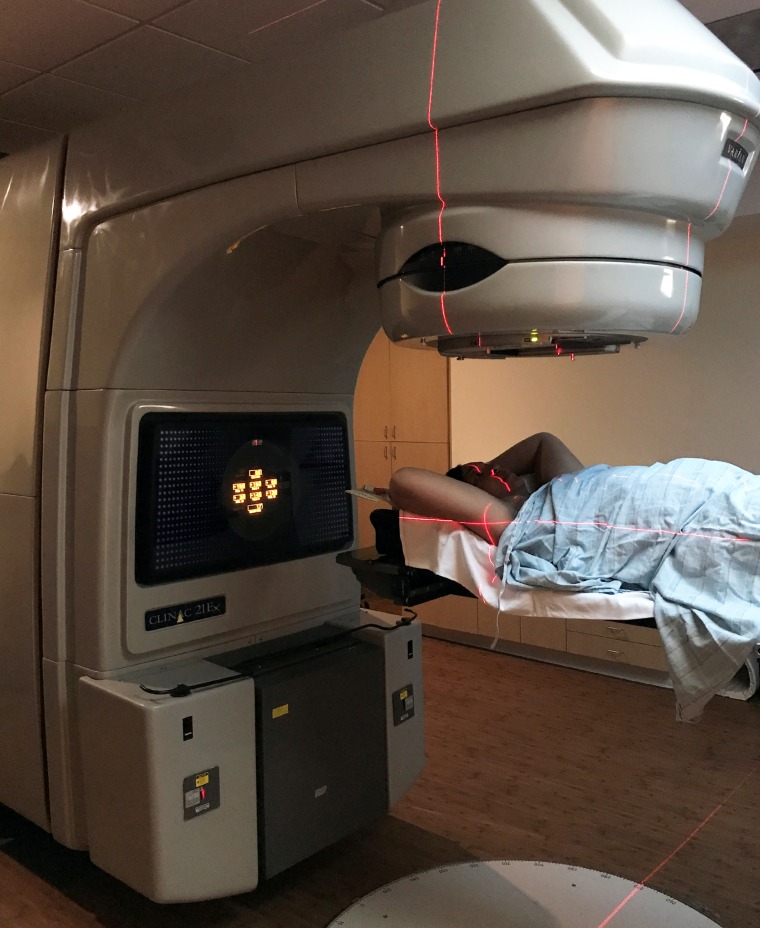

After surgery, she underwent six weeks of radiation and was in remission. After about a year of recovery, she had her left breast removed, as well, and she underwent breast reconstruction surgery.

During her treatment, she learned that parabens, a type of chemical used as preservatives in cosmetics, had been linked to breast cancer in Black women. She and her sisters stopped using those products.

“Once I got diagnosed, my sister (encouraged) us to have all natural hair,” she said. “What you put into your body, it really makes a difference because some of these chemicals, you really don’t know what they’re going to do.”

Black women, breast cancer and parabens

Black women are 41% more likely to die of breast cancer than white women, according to the American Cancer Society.

“It’s a different world of being a Black woman with breast cancer and being a white woman with breast cancer,” Dr. Niki Patel, an assistant professor in department of medical oncology and therapeutics research at City of Hope, told TODAY.

“Black women, despite having fewer breast cancers, die more frequently. Their mortality rate used to actually be lower than white people before the 1980s, before mammograms were prevalent. In the ‘90s, 2000s, the mortality rate (gap) is only getting wider.”

There are many possible explanations for the gap in mortality, and it's complicated to understand why it emerged and is getting wider, TODAY previously reported. But researchers are investigating various theories — such as the social determinants of health (aka the social and economic factors that can affect a person's or certain demographic's health) and biological differences in ancestry and gene expression, Dr. Veronica Jones, assistant professor in the divisions of breast surgery and health equity at City of Hope, said.

“A lot of research is being done, but we don’t yet understand all the reasons propelling the disparity," she told TODAY.

Black women are also more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer before they turn 40, which may be due to exposure to parabens — chemicals, found in hair care products and other cosmetics, that disrupt the endocrine system and mimic the effects of hormones in the body, according to experts at City of Hope, which is conducting research into the connection.

Lindsey Trevino, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the division of health equities and department of population sciences at City of Hope, shared the results of a study looking at parabens’ impact breast cancer cells from Black women at the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting this past summer. The study showed that parabens encouraged growth of breast cancer cells from Black women, which did not occur in cells from white women.

“Research is being done on social determinants of health and these environmental factors that disproportionately affect Black women, and how they have maybe increased the incidence of breast cancer, itself, or (the incidence) of aggressive breast cancer,” Jones said. “We’re looking at that link and how parabens, in particular, affect the hormones and also how they affect the therapies that Black women receive for breast cancer.”

Black women are also more likely than white women to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a later stage, according to the American Cancer Society.

Jones said that sometimes breast cancer patients worry that they did something to cause the cancer, and she reassures them that their individual actions aren’t to blame.

“Patients often if they asked me, ‘What did I do to cause this?’" she said. “There’s no simple answer. That research is complicated. But we are taking the necessary steps to do the detailed analysis and really tease out what is driving aggressive biology and breast cancer. Is it the parabens or is it something else? It is hard work, but we are doing the hard work.”

Life after cancer

When Love experienced pain or complications from her treatment, she thought of her five children. Being their mother helped her stay strong when life became tough, and her positive attitude helped her take on her treatments and grapple with their lingering effects.

“Giving up wasn’t an option that ever crossed my mind. I had multiple nurses tell me, ‘Keep up your energy. I love your frame of mind, don’t lose that,’” she recalled. “I knew I was strong. But I didn’t now I was as strong as I am now.”

She’s now in remission but takes an estrogen blocker, which she’ll likely need for the rest of her life.

“The estrogen was feeding my cancer. My body was making too much estrogen,” she said. “If it’s going to help me lower my risk of cancer, I’ll take it.”

She remembers how scared she felt after she first felt the lump and doctors recommended she get a mammogram. Now, she regrets waiting and encourages other to be brave.

“I didn’t think it could be me, and there are a lot of women that I’m sure that are out there just like me, saying ‘Oh no, it’s not me.’ And that’s really scary,” Love said. “You don’t think you’re going to be that one in eight, and it really could be you.”