Patricia Weltin fought relentlessly to have doctors finally recognize the rare diseases that have ravaged her two daughters’ lives — hypermelanosis and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Olivia, 19, has a deformed hand and foot, as well as scoliosis. She has undergone 21 surgeries, including one for a tethered spinal cord. Hana, 16, just had a hip dislocation.

“As a mom watching one child in pain is so very hard,” said Weltin, a single mom from Rumford, Rhode Island. “Watching both children in pain is unbearable.”

Some of Olivia’s teeth have fallen out and for a time, she has been in a wheelchair. Both girls have dark whorls on their torsos from hyper-pigmentation.

“One of the biggest issues of a rare disease is isolation and loneliness,” Weltin, 54, told NBC News. “Olivia has no friends. None. No one comes to visit and my heart breaks.”

So Weltin founded the Rare Disease United Foundation, which this year has created an art exhibit —portraits of real children suffering from 32 different conditions and designed to raise awareness among doctors for better diagnosis and research.

In the first month, the exhibit, “Beyond the Diagnosis,” was viewed by 100,000 people at medical schools around the country. It debuted at Brown University in February and is scheduled to go to Harvard Medical in November and then on to the National Institutes of Health in 2016.

There are more than 6,800 rare diseases, which altogether affect about 30 million Americans, half of them children, according to the National Institutes of Health. A rare disease is one that affects fewer than 200,000 people.

Parents often trudge from doctor to doctor, on average eight years before getting a diagnosis, because these conditions are so unfamiliar in the medical world.

“We often live in poverty because of the medical bills. Even people making a good living struggle,” said Weltin.

Dr. Craig Eberson, associate professor and chief of the division of pediatric orthopedics at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University, said the impact of the art exhibit has been “fantastic.”

“We get so silo-ed with so much information and no general guides [on rare diseases],” Eberson told TODAY. “When someone has a broken leg, it’s straightforward, but with complicated symptoms, you tend to think the patient is crazy or malingering.

“Until someone figures it out, families carry an enormous load of frustration and anxiety,” he said. “You have to take that into account when you treat patients: to look at the person and not the disease. It will make better doctors.”

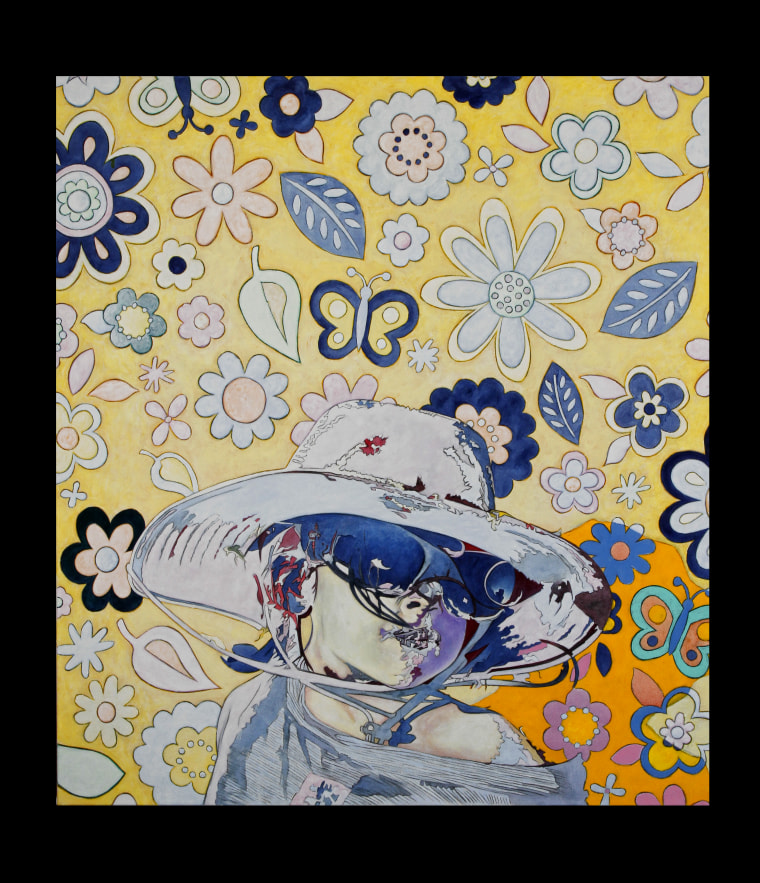

And that's exactly what the art exhibit does. Parents provided photos of their children and noted artists donated their time and skill to create portraits — some abstract and some true to life. They had never met the children.

Justine Raygor of Vancouver, Washington, agreed to participate in the exhibit. She was 26 weeks pregnant with her daughter Malia when her 2-year-old Conner was diagnosed with Sandhoff disease, a neurodegenerative disorder so rare, there were only two other cases at the time in the United States.

Malia also has the disease. Similar, but more severe than Tay-Sachs, Sandhoff typically kills children before the age of 5.

“At first, no one knew what it was,” said Raygor, 27, of Vancouver, Washington. “It was difficult and I was always worried about choking I went almost a year and a half with no sleep before I could get nursing help.”

Conner died in May at the age of 4, but Malia still struggles with mental and motor deterioration. Raygor decided to leave the portrait in the exhibit in the hopes it would help raise awareness for research.

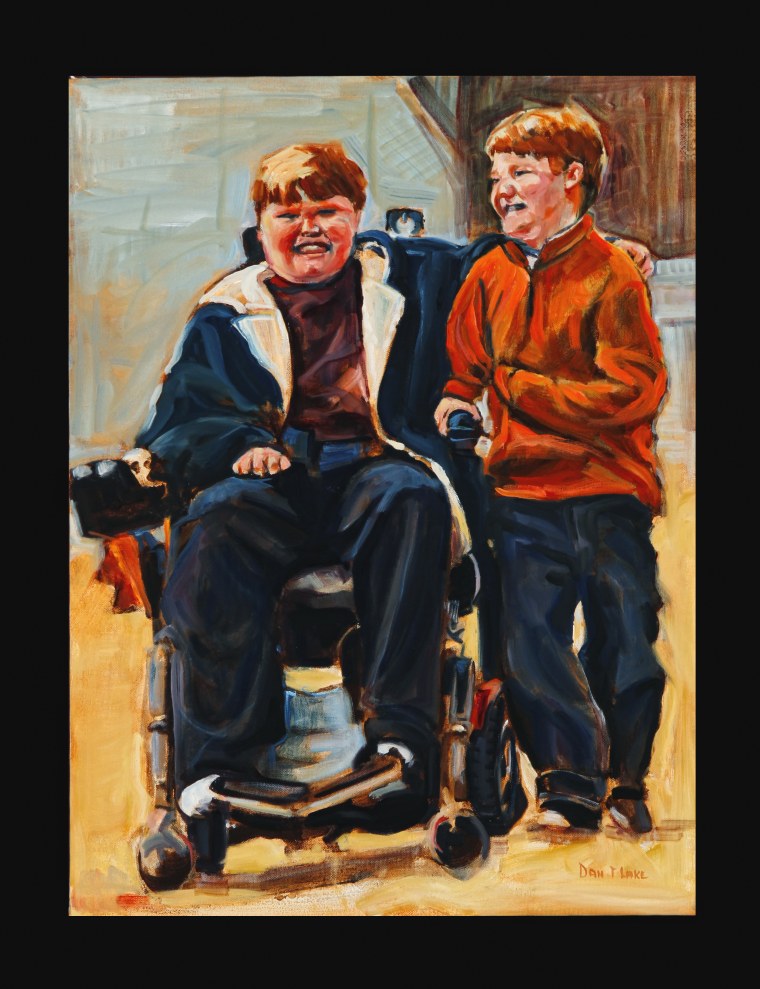

Jenn McNary, 34, of Pembroke, Massachusetts also included her sons’ portraits in the exhibit. Austin, 16, and Max, 13, have Duchenne muscular dystrophy and are in a clinical trial for an experimental drug.

“We showed up at the exhibit and there was my kids’ painting on the wall,” she told TODAY. “I especially loved it because they are giggling with their arms around each other.”

“The pictures are a way of capturing these kids not looking ill,” said McNary, who is director of the Jett Foundation. “The idea is to look at them as beautiful human beings.”

“It certainly helps raise awareness for someone who has not seen a rare disease,” she said. “And when you go to an art exhibit and not a medical one, it might inspire awareness and get the regular world involved.”

Weltin has launched a “Beyond the Diagnosis” Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for expanding the exhibit.