A recent afternoon walk turned into a tick attack for a Massachusetts man.

As community forester Derek Lirange was hiking around the Tower Hill Botanic Gardens in Worcester on May 16, he spotted a few ticks on his pants. Within a few more minutes, there were five or six more ticks, followed by more and more. By the end of the hike, he counted 26 ticks.

I hadn't taken every precaution, such as spraying with insect repellent, but I was wearing long pants and socks," the 26-year-old told TODAY. "It was a creepy, ongoing discovery."

Luckily, none had embedded. But the spike of the tick population in the gardens led to the cancellation of a spring walk around the reservoir.

Welcome to the new tick season. No one knows exactly how many ticks are out there, but the skyrocketing cases of tick-borne diseases recently reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides indirect evidence that the little bloodsuckers are becoming more numerous, said Alfaro Toledo, an assistant professor in the department of entomology at Rutgers University.

“It’s a big epidemic affecting the entire East Coast,” said Toledo. “Witness the spread of the deer tick to the north and west.”

And it’s not just deer ticks we now have to worry about. The numbers of Lone Star ticks, which can trigger an allergy to red meat, are also on the rise and their habitat continues to expand, Toledo says.

In its recent report, the CDC said there have been seven new tick-borne viruses discovered to infect people since 2004.

Why more ticks?

One big factor leading to the so-called tick explosion is the overall warming trend. But there are several factors beyond warming weather driving the rise in tick numbers, experts say. One is the booming numbers of deer and rodents. Deer, which are the preferred hosts of adult ticks, are increasing in numbers, “because basically there are no predators anymore,” Toledo says.

More deer means more female adult ticks go on to lay eggs.

High numbers of rodents also drive the numbers of ticks. After hatching from eggs, tick larvae attach to rodents to feed and, unfortunately for us, pick up diseases like Lyme and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Once the larvae get their meal of blood, they move on to the next phase of their cycle, the nymph stage, which is when they’re most likely to latch on to a human.

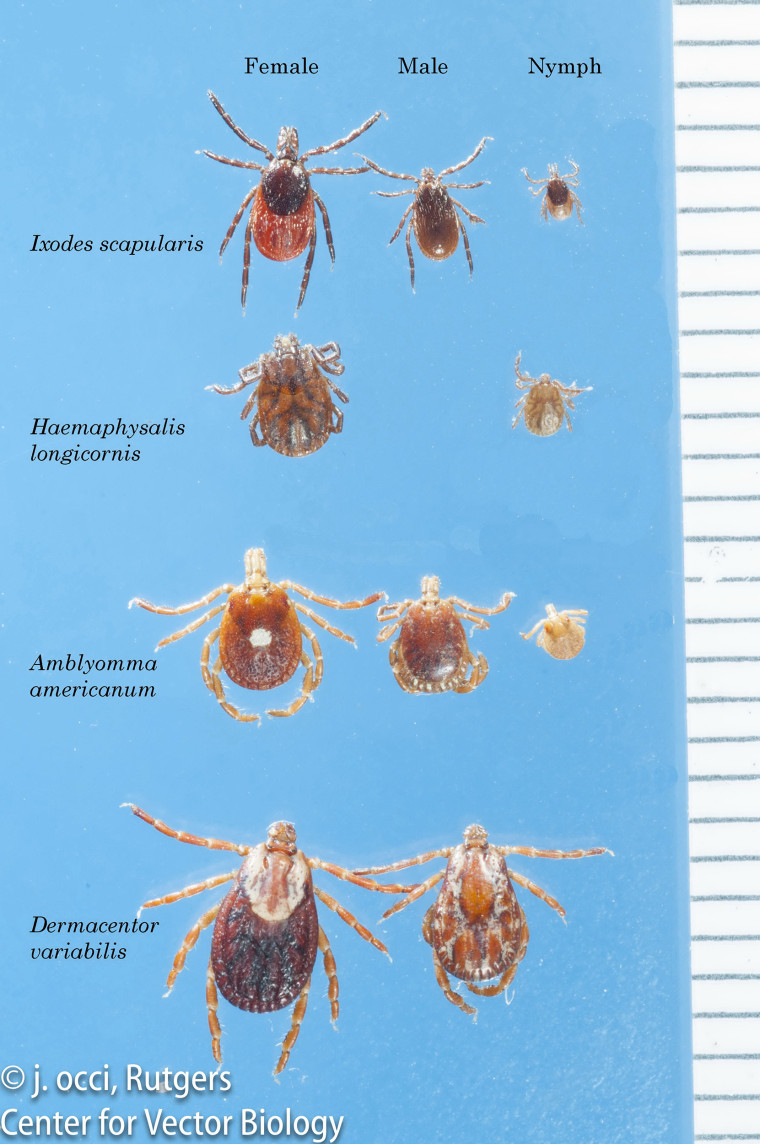

Though both nymphs and adults can transmit disease, the nymphs are more likely to do so because of their small size. Adult ticks are big enough to be easy to spot and get rid of before they can pass on diseases like Lyme. Nymphs are much smaller and often attach long enough to transmit disease without our ever spotting them.

And while deer ticks are most likely to be the ones transmitting Lyme and lone star ticks, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, dog ticks and a new invader, the Longhorned tick, can also carry and transmit disease.

Experts used to tell people they’d be safe from tick bites if they kept their lawns mowed and stayed out of wooded areas—and that’s still mostly true for deer ticks. But Lone star ticks and dog ticks, which both can carry diseases and bite humans, are perfectly happy roaming through mowed lawns, said Matt Frye, an entomologist at Cornell University.

Frye says we should just accept that every year now is going to be a bad tick year. That means we should get serious about examining our bodies for ticks. “You should do a tick check every day, like you brush your teeth every day,” he said.

The situation isn’t entirely hopeless. Though there are no real natural enemies of ticks, researchers are working on some ingenious ways of knocking their numbers back. One method currently being tested in communities with high numbers of ticks is to treat rodents with tick-killing substances, Frye said. Boxes baited for the rodents give them a dose of the same tick poison used to protect dogs.

The idea is that if you can lower the numbers of ticks that make it to the nymph stage, fewer people will be infected. That method is still being tested, so it won’t help any of us right now.

In the meantime, if you do spot a tick and want to know what kind it is and whether it’s carrying a disease, you can send it to a lab for testing, said Laura Goodman, an assistant research professor at Cornell.

She suggests you place your tick in a sealed, escape-proof container and ship it to Cornell or one of the other certified labs around the country. One of the best ways to kill the tick, Goodman says, is to place the container in your freezer. The shock from going directly from warm weather to freezing temperatures will be enough to do in your tick, she said.

TODAY.com writer Meghan Holohan contributed to this report