In 1948, Budweiser published an advertisement featuring an illustration of former President Thomas Jefferson serving a plate of pasta to two unknown constituents. In the ad, Jefferson smiles as he lifts and daintily twirls a strands of spaghetti; the caption reads, “Our third president was our first spaghetti maker.”

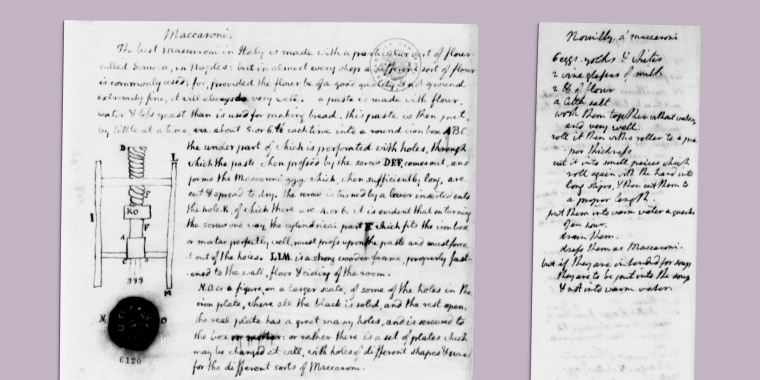

This is, of course, untrue: First, he likely never cooked dinner himself, considering he enslaved 600 people, several of whom worked in the house’s kitchen and are mysteriously missing from the image. And while he did bring a spaghetti machine to the states, his love for macaroni has been better-documented— including in other advertisements from a more recent time in history.

Most telling, however, is the omission of his enslaved chef, James Hemings, who was the mastermind behind many of America’s favorite dishes, including macaroni and cheese, but also ice cream, french fries, whipped cream and more. His erasure is part of a theme that’s permeated written history itself.

In Amazon Prime’s new documentary “James Hemings: Ghost in America’s Kitchen,” narrator chef Ashbell McElveen invites Jacques Pepin and other culinary experts to grapple with Hemings’ distinction as the first American trained as a master chef while also being the brother-in-law and enslaved property of Thomas Jefferson for most of his short 36-year life.

Throughout the documentary, audiences are faced with these dichotomies, specifically how so many dishes we call staples in this country are not credited to the man who literally brought them to this country from France.

“I started putting pieces together as a culinary historian because there were limitations to what Jefferson and other white historians had written down,” McElveen tells TODAY Food, adding that to find snippets of truth, where Hemings’s reality was mentioned, he examined the oral records of African Americans such as Isaac Jefferson and others.

"For me, it was like sitting in a Black barbershop on a Saturday morning,” McElveen says of diving into the records. “You heard all of these things, all these stories and everything was discussed. It had nothing but the ring of truth to it all. I began to look further.”

What most history books have managed to record about James Hemings is that he was born in 1765 to Elizabeth Hemings, a Black enslaved woman, and John Wayles, a white slave owner. At age 9, James Hemings was brought to Monticello along with several of his siblings and his mother as part of the inheritance of Martha Wayles Jefferson, Wayles’ daughter and Thomas Jefferson’s wife, when Wayles died. (This made James Hemings the enslaved half brother-in-law of Thomas Jefferson.)

In his teen years, Hemings worked as a riding valet, but it was a 1784 trip to Paris with Jefferson where he was trained in the art of French cooking that put him on the track to becoming a master of fine cuisine.

McElveen says that Heming’s first stint of training in France was with caterer and restaurateur Monsieur Combeaux for two years. After Hemings worked in Combeaux’s kitchens, he went on to be trained in French pastry, apprenticing with several pâtissiers, which included one working in Chateau Chantilly, the household of the Prince de Condé.

“He was an extraordinarily bright young man who was completely literate,” McElveen says, emphasizing the rarity of an enslaved person who could read or write. While in Paris, Hemings paid a French tutor with his wages earned (because in France he was legally free and therefore required to be paid) to become bilingual in French and English, which also likely was a first for an enslaved person.

“I literally grew up in the same training tradition that hasn’t changed in all those years and it took me eight years to achieve what seems like Hemings did in less than two years,” says McElveen.

While it’s true that Jefferson used haute cuisine to impress constituents during his years as a politician and president, it was Hemings who made the food, adapting the recipes he learned in France for an American palette.

By 1789, Hemings had returned to the States with the Jefferson family, his many skills and tools of French cuisine. Jefferson was appointed the first Secretary of State in 1790 and used Hemings as a chef and valet in that time, where he impressed guests of the Jefferson household with dishes such as snow eggs, a custard-like dessert that bears a striking resemblance to the ice cream recipe that was found in the Jefferson Papers and one for "macaroni pie," a tweaked version of the French bechamel-based dish that we now know as macaroni and cheese in the States.

That first year back, Jefferson hosted a dinner colloquially known as the Dinner Table Bargain. On the evening of June 20, 1790, Jefferson hosted a dinner to bring Alexander Hamilton and James Madison together, who were essentially arguing over where the nation’s capital would be.

After a meal and much discussion, everyone agreed on the banks of the Potomac River now known as Washington, D.C. Who do you think cooked the dinner that literally brought a nation together?

Returning to Monticello in 1794, Jefferson promised to free Hemings if he trained another enslaved person to cook like he did, and Hemings trained his brother Peter Hemings for the job.

In historic records, there are inklings that Hemings transformed that transformed the concept of cooking in America through Monticello’s kitchen, with a kitchen inventory that included ice cream molds, copper pots and more.

Hemings finally left Monticello with $30 and his freedom in 1796, and for five years, he worked in Philadelphia and possibly Europe before settling in Baltimore — but Jefferson wasn’t done with him yet.

“Jefferson was elected President by Congress, not by the people for his first time in office,” McElveen says, adding that Hemings was working in Baltimore when Jefferson sent for him to work as White House chef in 1800.

“He refused to come as he was called, as slaves were often told, ‘Come here.’ James said, ‘Listen, if Jefferson would be so kind as to write the two lines of appointment or invitation,’ that he would work for him,” says McElveen, adding that Jefferson ultimately refused to write that letter. “Because for him writing a letter to a Black man was recognizing him as a man, not as property. But James Hemings stood his ground and stood up to the most powerful white man in his universe: the President of the United States.”

Hemings never reached the culinary heights his abilities would have likely led him to, dying just a year later, at the age of 36. His contributions were quickly paved over, as the contributions of many enslaved people have been throughout history.

“In this country’s culinary history, there has been a deliberate gaslighting of the original historic contributions of African Americans in American culinary history. To me, that’s culinary theft,” McElveen says, adding that “The Virginia Housewife,” a famous cookbook by the sister of Jefferson’s son-in-law, is a prime example of what McElveen calls a probable historic theft of ideas.

“Mary Randolph Jefferson has many French recipes in the cookbook and all are attributed to Jefferson’s daughter or even herself,” he says. “Neither of them had ever been to France or even cooked in the kitchen. So it stretches the imagination to believe something like that.”

This Thanksgiving, before you tuck in to a heaping bowl of macaroni and cheese, or scoop some ice cream onto your pumpkin pie, McElveen asks us all to remember the long path through history it took to get to our tables.

“His macaroni and cheese recipe that went from an enslaved kitchen in Monticello all around the world and became a global food, just like french fries — not from its country of origin but from the enslaved at Monticello,” McElveen says, emphasizing his commitment to combating the erasure of the contributions of African Americans to fine dining in the U.S.

"It’s not just Thanksgiving dinner," says McElveen. "We should all give thanks for this incredible individual who helped create fine dining in America.”