During Hispanic Heritage Month, TODAY is sharing the community’s history, pain, joy and pride. We are highlighting Hispanic trailblazers and rising voices. TODAY will be publishing personal essays, stories, videos and specials throughout the month of September and October. For more, head here.

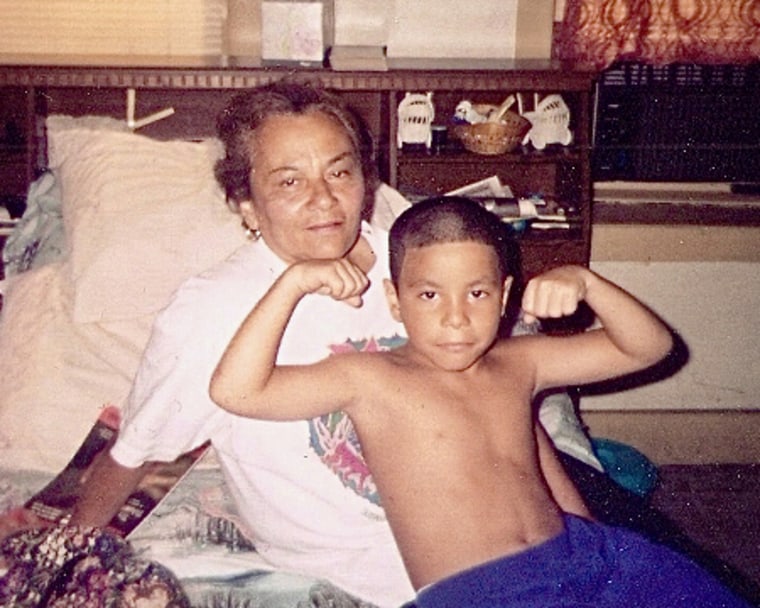

I don’t know what my then-60-year-old Puerto Rican grandmother was thinking, raising me, her already rambunctious grandson, when she started regularly serving me café colao (or colado for the uninitiated) as a 4-year-old child. She'd then lace the café colao with whole milk and a hefty scoop of white granulated sugar. My abuela, whom I called Mami, my sole parent, my only caregiver and my sometimes barista, made the powerful concoction for me my entire childhood. Back then, her Bustelo made me vibrate from my curly brown hair down to my Flintstone toes. I loved it. She’d pack me full of sugar, caffeine and carbs, and we’d trade stories like old war buddies.

For years, my mornings began with the sound of a coffee tin lid being pried open and the aroma of the finely ground espresso beans that Mami used filling the air. The smell wafted through our two-bedroom railroad-style Brooklyn apartment, gently caressing my nostrils, lovingly waking me from deep sleep. Dreams swirled in my mind of biking through the bodega, riding Snuffleupagus down Sesame Street, or of Walter Mercado emerging from the mist with a crystal ball. Still, even these fantasies were no match for what beckoned from the real world: my abuela’s brew.

My abuela struggled all her young life and escaped to New York City the moment she could. I think that struggle is what made her decide to raise me on her own when she was 56 and I was a defenseless 3-month-old. With no father to speak of and with my mother in and out of the prison system, I’m sure my abuela saw herself as she looked down at my helpless squishy baby body. She knew she couldn’t let the world do to me what it had done to her. As my guardian, she pored over me with the same love and precision I’d later see her put into making her café con leche.

The stories of her struggles were hard to hear when she’d open up to me those mornings at the table. She’d speak of those times nonchalantly over the cubes of cheese she’d leave to melt and float aimlessly in her café as she stared off into the distance, reliving it all. She’d eventually come back to me from that faraway place, smile and scoop the cheese out with a piece of bread. I never did partake in the cheese float then, but perhaps I’m ready to float now.

It could have been because we were poor, or maybe because my grandma was old-school about her café, but we didn’t have one of those fancy coffee machines or even a cafetera, better known as a mocha pot. No, no, dear reader, we had a colador, or as I called it, "The Sock." A simple object. An off-white sock-shaped cloth filter held open with metal wire and a wooden handle. It’s more akin to the pour-over method you see at upscale gentrifying coffee shops now, but back then, the sock felt archaic, closer to the coffee, intimate with the grounds.

To make café colao, some pour water into the sock exactly like pour-over, but my grandmother would boil water in a metal pot shaped like a milk-frothing pitcher atop the stove, with the sock placed inside of it and the coffee grounds inside of that. When the coffee was brewed just right (she always instinctively knew when that was), she’d lift the sock by the handle, grab it barehanded and then tightly squeeze the pouch with her perfectly manicured arthritic fingers, unfazed by the scalding heat. She’d warm the milk separately in a small saucepan, carefully scooping out the burnt coagulated milk that formed at the top, which she called nata, with a spoon. She’d then combine the steamed milk with the coffee, pouring the magic elixir into two ornate tazas atop saucers. Finally, she’d place them where we always sat: her at the head of the table and me at her right hand.

The mornings were quiet back then. Everyone in my family was spending time "Upstate" — for this sweet story’s purpose — and for what seemed like a lifetime, it was just the two of us. How lovely it was: no phone-ringing, email-dinging, notifications or reminders. Even the hum of computer fans and screeching modems wouldn’t enter our analog existence for years.

While sometimes we sat in silence (specifically when Mami was engrossed in the words of NYC AM radio personality and mystic Anita Cassandra as she recited the day’s lucky zodiac-specific numbers), much of the time, we spoke in Spanish for hours. I’d give anything to remember every conversation verbatim now. It’s not a thing you understand in the moment will be important later on. Time makes fools of us all, it seems.

Still, it was during those beautiful, long, laugh-filled talks, over that hot café con leche, buttered pan sobao or Puerto Rican sorrulitos covered in cinnamon sugar (if I was lucky that day), that I formed in my mind who my abuela was. And what I learned is that she was forged from fire.

My abuela was born into a small family. She had a sibling she could no longer remember but deeply yearned for. A mother who passed before she could memorize the smell of her hair. And a father who couldn’t bear to raise my grandmother on his own in Puerto Rico during the Great Depression.

For several years, my grandmother got passed from household to household — until she landed in the home of a pair of farmers, whom she called "mamá y papá" in the stories she recounted to me. The farmers were tough on her. She was expected to help. In truth, she was the help. She fed the cows and chickens and tended to the pigs and sheep. She cooked for the biological sons of the farmers, who returned the favor by bullying her. Her head was often shaved to prevent lice, and she was sent to school in tattered clothes. She constantly dreamed of running away and of a better life.

In our stolen moments having cafecito together, we bonded. Over our shared sorrows. Over our loneliness. Over caffeine. We grew together, and then apart during my rebellious years, then came back together when I was in college.

The phrase many of us long for but seldom get from our parents, especially as the children of Latino parents who never heard it themselves, is: “I’m proud of you.” Instead, we have to make do with other acts of love or attentiveness. And although she could never muster those exact words, every time I visited from school when I was away in Boston, I’d wake up in my childhood bedroom and feel her pride. Because right next to me, placed gently with much care and love, would always be our greatest shared experience: a cup of homemade café.

It was everything she could never say and all I needed to hear in one steaming cup.