In the 1920s, the British Museum acquired several incredibly well-preserved pastries from a 1,300-year-old tomb in the Astana Cemetery in Xinjiang, China. Their variety and beauty is captivating, so evocative of what life must have been like along the Silk Road long ago; although the ancient travel network is largely associated with the exquisite fabrics that were traded from Mongolia to the Mediterranean, it also allowed the exchange of art, tools, ideas and every imaginable food. The result was an explosion of cultural exchange, fusion and innovation. The exact forms of the pastries made there and then would look perfectly in place in the finest bakeries in the world today.

These cookies were found at a time when archeology unfortunately amounted to little more than plunder, and in any case, the tomb in question had reportedly been emptied many years before. Still, it’s painful to read the archeologist’s cavalier and colonialist description of his finds, which were controversial even at the time. The Chinese inscriptions at the tomb doors, which likely would have told us something about the person for whom these pastries were laid to rest alongside to nourish them in the afterlife, are dismissed as an only vaguely interesting footnote that another scholar might or might not get to at some point later on.

As much as I wish it were possible to know about the people buried there and why foods like these were chosen for them, I wish much more that I could travel back in time and be a fly on the bakery wall as the cookies were made. The skills involved are many, and they had no temperature-controlled electric ovens, no silicone mats or spritz cookie dies. Given the time and place, although the tomb was likely Chinese, the ingredients, techniques and recipes could have originated anywhere in the Eastern Hemisphere. A scientific investigation of the microscopic starches determined that they are largely wheat-based, but as to the type of fat, sweeteners, leaveners and fillings, I had to make educated guesses. To try to replicate these little wonders, I used my own experience in the kitchen since I was a child, decades of watching Food Network, food science classes I took as part of my professional training, my beloved cookbook collection, and a recipe published by Gastro Obscura (which was adapted from Eran ud Turan). It also took some trial and error.

Ingredients

The study of the starches also mentions bran fragments, so I decided to use part refined flour and part King Arthur White Whole Wheat Flour. The latter is very finely milled and works well for most pastries even though it is whole grain. Sugar cane has been in use in Asia for thousands of years, but I’m guessing it wasn’t quite as refined at the time, so I used a combination of unrefined turbinado and regular white sugar to approximate what might have been found in the finest pastries available at the time. Butter would have been widely used as well and easy to work with in a chilly climate. These survived the eons so well that I feel it’s likely they included a protein binder, most likely egg, although some cookies made in the area now don’t use them. There would have been many fruits to choose from for a jam tart, but I went with two that were widely available then, apricot and plum. Lastly, I chose some of the spices that have a long history of use in pastry and that the Silk Road was famous for conveying: cinnamon, cardamom and anise.

Techniques

Millefiori Cookies

I started with the circular and triangular cookies on the top left and right of the group photo. There’s so much detail in their scrolling designs. The British Museum description notes that they seem to have been made from layers joined together and then rolled out, and I think that’s precisely correct. If you’ve ever made polymer clay beads, you may have used this technique yourself. You roll out a thin layer, make stacks or rolls, form them into a cylinder and roll it until they are joined with no air spaces.

For the cookie version, it’s important to use a pretty standard roll-out sugar cookie dough with relatively high fat content and relatively low liquid content, so that they don’t puff up or spread much. The only leavening is egg. It’s also very important to chill before forming, and again before baking. You can then cut thin slices and roll to the proper thickness for baking. It’s hard to say given how long these have aged, but I think it’s likely that the lines on these cookies were highlighted by brushing butter and spices over the rolled out surface prior to forming the stacks. I chose cinnamon with a little cardamom, and it’s a lovely familiar and warm sugar cookie flavor. To make the triangular one, I smacked the chilled dough cylinder on the counter a few times to flatten the sides before slicing.

Knotted Cookie

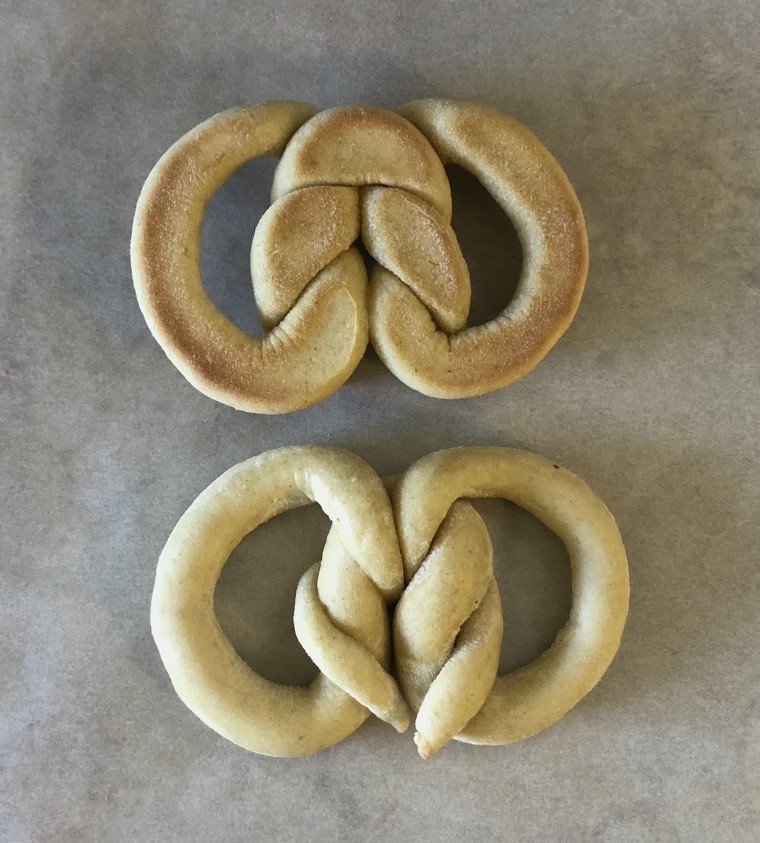

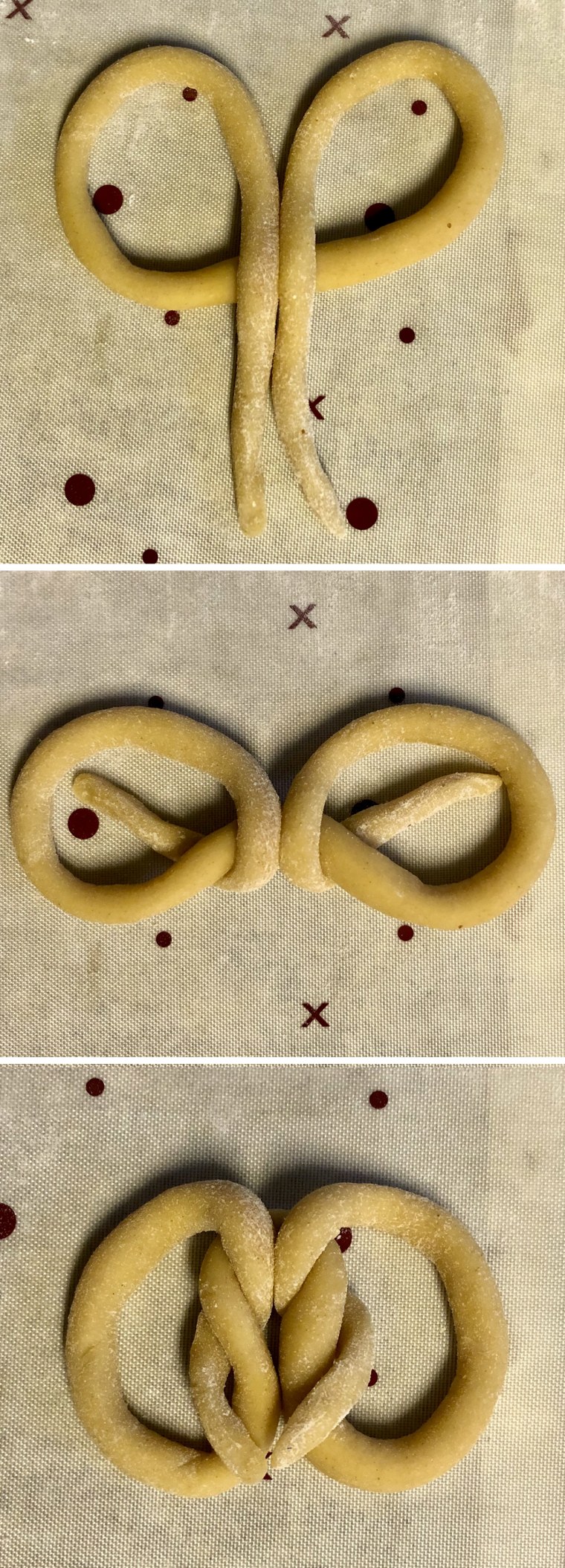

The center top cookie took a little more experimentation. The British Museum notes theorize that it was made out of three loops of dough, and although it’s hard for me to say for sure without seeing the other side of it, I think it actually represents single, long rope of dough tied in a half-knot on either side. To get the right size, it took a tapered rope over two feet long, and to get that to hold together, the dough had to be quite low in sugar and with much more flour than the usual sugar cookie.

Again, there’s no leavening other than a little egg, because I didn’t want it to puff out of shape. I also brushed it with cream and egg white and baked at a relatively high temperature to seal that smooth surface you can see in the original. The final dough ended up pretty close to an Italian anise twist cookie I used to make many years ago, so I flavored it that way. It’s not very sweet, something like a cross between a soft pretzel and a scone. It’s so beautifully formed that I think it was probably made by grasping the rope with both hands in just the right spots and flipping it around in a certain way to make the knot with centripetal force. Physics can achieve perfect circles and twists much more quickly and reliably than the way I did it. (If you doubt that’s possible, I invite you to watch expert noodle makers at work!) Interestingly, I’m pretty sure this one is displayed in the museum photo upside down. Oops!

Filigree Cookie

The cookie in the middle bottom is my favorite. The museum notes say it isn’t clear whether it’s molded or piped, but I feel pretty confident that it was piped; it would be near-impossible for a molded cookie to keep its shape coming out of the mold with such fine bands. I used the sugar cookie dough from the millefiori cookie above but added cream and let it warm up a bit so that it would be soft enough to pipe. This is similar to what you would use to make spritz cookies. I’m not an expert piper by any means, but with a simple star tipped piping bag and a little practice, I got something pretty close to the original.

In retrospect, I wonder whether the original might have had a little leavening, or maybe a bit more egg by volume. It appears to be just a little puffy compared to mine.

Jam Tarts

There’s no scientific analysis to determine what exactly is in the depression in the cookies on left and right bottom, but the consensus is some kind of fruit or jam. If you’ve ever made thumbprint cookies, congratulations! You’ve reproduced a 7th century artifact right along with me. The one on the right looks as though it has had the back of a knife pressed in all around, the way you might do with a pie crust today. I used the sugar cookie dough and filled mine with apricot jam — and it was delicious. I think the original might have had less egg in it, though. It looks like it kept its shape during baking almost exactly, the way shortbread might.

The ancient version of the one on the left is just gorgeous. The museum makes reference to scoring to make the petals, but this one reminds me so much of a wooden ma’amoul mold in my possession that I think it must have been molded similarly.

Ma’amoul cookies are a delightful date- or nut-filled semolina cookie made for Eid celebrations. The jam tart has a filled depression rather than an enclosed filling, though. So, I tried the sugar cookie dough and I wasn’t satisfied. It spread and lost the detail. Instead, considering the similarity in color and texture, I did something you would never do for a traditional ma’amoul and floured the mold so that I could try the knotted cookie dough. That worked much better. I think if the mold had been more deeply carved, it would have yielded a very similar result. The ancient one seems to have an actual piece of fruit as well as some jam residue, so I deepened the well with a teaspoon and filled it with a piece of dried plum (yes, a prune!) and some apricot glaze. It tasted a lot like a scone with jam. They’re very sturdy, not too sweet and so beautiful. I’m going to keep these breakfast-y gems in mind the next time I need to bring cookies to a brunchtime party.

This project was so much fun, and such a great way to practice different techniques. It wasn’t as difficult as I worried it might be at the outset, because there are so many good food science references available. I’ll never know how close I came to the ancient ones, but I’m not going to let that stop me from eating them.