Cara Nicoletti is a fourth generation butcher — but she also wants people to eat less meat.

In order to do that, she’s making sausages. In 2019, the 34-year-old butcher founded Seemore Meats & Veggies, a company that makes colorful sausages packed with fresh vegetables (up to 35% per serving) combined with certified humanely raised meat.

“I want butchers in the future to not be scared of people eating less meat,” she told TODAY Food. “I hope that that's the way that the world is going. And I don't necessarily think that it puts us out of a job. I just think that we need to get a little bit more creative about our job."

Nicoletti's sausages are bursting with that creativity in every bite. Hot Monterey Jack cheese comes oozing out of her Broccoli Melt sausage (if it’s Loaded Baked Potato, then it's gooey cheddar); tangy beet juice seeps out of La Dolce Beet-a, and a powerful punch of dill comes from Bubbe’s Chicken Soup.

With potential meat shortages looming in U.S. supermarkets due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, Nicoletti believes her mission is more important now than ever.

"It's been very scary, but luckily we were already navigating the world of operating outside of 'big ag' (Tyson, Pursue, JBS)," she said. "We work with places that treat their workers really well and they are being extremely careful. So far, we're OK, but monitoring it every second.

"This pandemic has really exposed a lot of dirty meat industry secrets that, luckily, we have no part in."

Nicoletti's 90-year-old grandfather and retired butcher, Seymour Salett (the company’s namesake), told TODAY he believes she has revolutionized the sausage business.

“Nobody had the imagination to remake the sausage the way Cara has made," he said.

According to 2018 data from the U.S. Department of Labor, women now make up about a quarter of butchers, which is up from 21% in 2006.

Women make amazing butchers, Nicoletti explained, because “They’re less afraid to ask questions. They're less afraid to admit when they're wrong.”

Butchery is in her blood

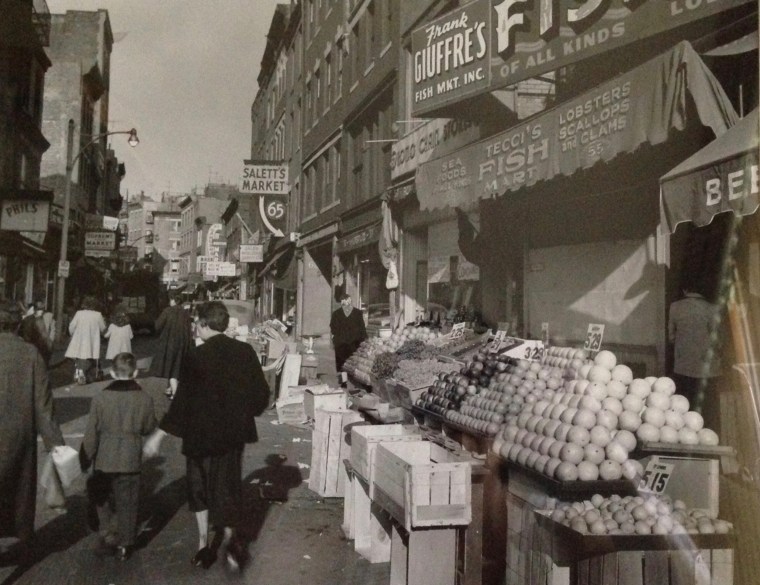

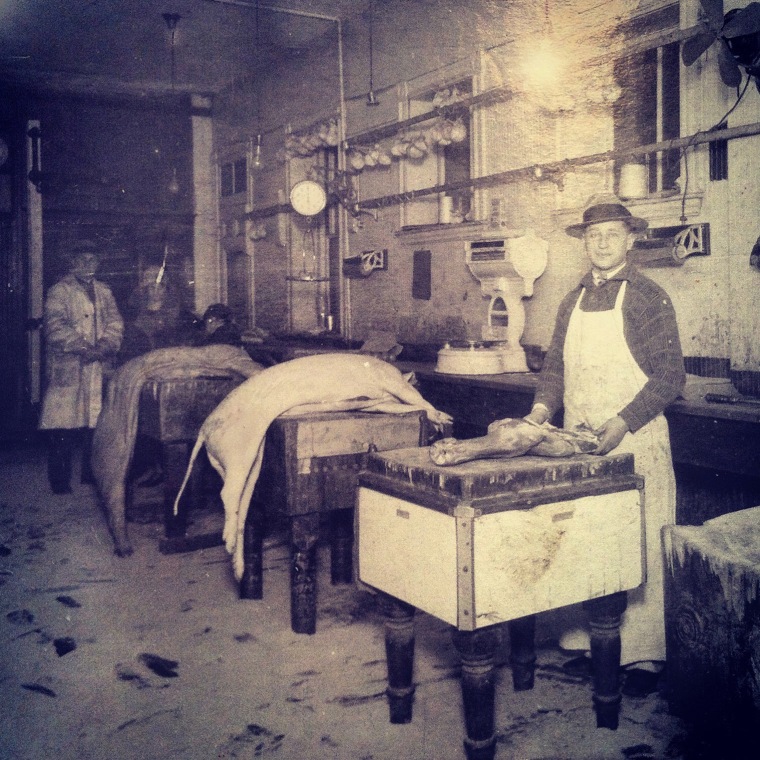

Nicoletti’s family’s history in butchery started with her great great grandfather, who was a cattle merchant in Russia, and his son, her great grandfather Jack, who joined him in the meat industry. After immigrating to the U.S. in 1919, Jack Salett worked at a handful of butcher shops. In the 1940s, he opened his own store in the North End of Boston on Salem Street.

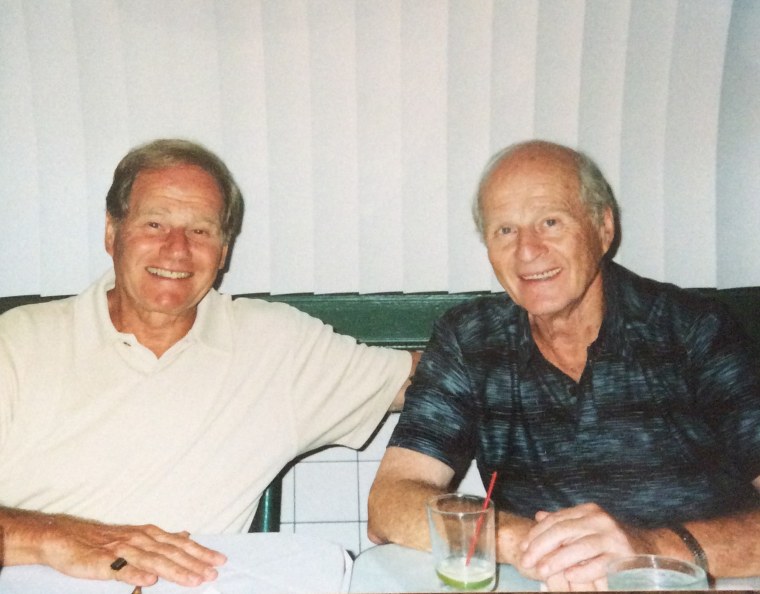

When Seymour Salett was 13, he and his brother Bobby started working at their father's shop. They eventually took it over in 1942.

“It was considered the rite of passage,” he said.

Salett and his brother were partners until they closed up the original shop in 2002. At that time, Salett expected his butchery lineage to end with him.

“I had three daughters,” he said. “I didn't think at that time that it was an industry for women. I never thought that my girls would be interested. And they weren't.”

But it just skipped a generation. Salett's daughters used to bring their kids into his butcher shop so he could take care of them while they went out and ran errands. Nicoletti was always intrigued by what was happening in the store.

“Cara always wanted to go into the ‘smelly room,’” said Salett.

“I was, out of my sisters and my cousins, probably the most curious about what they were doing in the shop growing up,” said Nicoletti. “I always wanted to sort of, like, peek behind the curtain and see — whereas my sisters and my cousins, not so much. They kind of didn't wanna know.”

Working with her hands

Despite her interest in the industry, Nicoletti hadn’t always planned to be a butcher. She went to New York University to study English and Latin. Initially, she had planned to get a Ph.D. in Victorian literature.

While she was in college, she worked at various restaurants, supper clubs, juice bars and coffee shops. Many of her friends took on less physical jobs, landing internships at magazine and publishing companies.

"I was so jealous at the time because I was working at restaurants, and I wanted to be able to do that kind of stuff for free,” she said.

But when Nicoletti graduated in 2008, the economy collapsed.

“It didn’t matter what you had done for four years,” she said. “There were no jobs.” Many of the people who had been interning at publications were asking her, “Is your restaurant hiring? Can I get a job washing dishes?”

“I felt very grateful that I had this skill, working with my hands, and I knew how to do something that made me employable.”

After graduating from college in 2009, Nicoletti started working at Brooklyn's Pies ‘n’ Thighs, a critically acclaimed restaurant known for its fried chicken, as a baker. One of the owners, who also had a grandfather who was a butcher, told her, "If you ever wanna do some, like, light butchery work, breaking down chickens and pork shoulders and stuff, let me know."

It turns out that butchering reignited an interest Nicoletti had first discovered at her grandfather’s shop when she was a kid. So, that same year, she went out walking around Brooklyn, asking every butcher shop if she could come work for free. They all said no — until she came across the Meat Hook. They told her to "come in tomorrow," and she started apprenticing there on her days off (and sometimes before and after work shifts) from Pies 'n' Thighs.

“I remember calling my papa, Seymour, when I got my first apprenticeship and he kind of laughed about it,” said Nicoletti. “But I could tell that he was hoping it was something that didn't stick.”

“Well, I said, you know, this is the funniest story, the funniest joke,” said Salett. “You're joking with me. And, you know, she said 'no.'”

“He said, ‘I worked my whole life so that you could sit at a desk and have clean hands,’” Nicoletti recalled.

But, after working with her hands for most of her life, Nicoletti knew that wasn’t going to change. “I enjoy the feeling of physical exhaustion much more than mental exhaustion,” she explained.

At the end of 2010, she left Pies 'n' Thighs to work at another Brooklyn restaurant known for its farm-to-table fare called Colonie. She was still apprenticing — for free — at the Meat Hook. At Colonie, the chef decided to start buying whole animals, but none of Nicoletti's male coworkers had ever been trained on how to break them down. So she volunteered to help and ended up taking on dual roles in pastry and in-house butchery.

"They were very long days," said Nicoletti.

At the end of 2011, the Meat Hook offered her a full-time position. Nicoletti eagerly left Colonie to take it. Along with other employees, she was responsible for loading in, breaking down and merchandizing whole cows, pigs, lambs and chickens, serving customers and making products, like sausage and charcuterie, to utilize the entire animal.

How the sausage got made

As soon as she started butchering full-time at the Meat Hook, Nicoletti gravitated toward sausage-making. It reminded her of baking — particularly in the recipe development aspect. “You're looking for a lot of the same cues in sausage-making as you are in bread-making,” she said. “So I felt very comfortable with it.”

Week after week, Nicoletti observed the same customers consistently coming in to restock their meat supplies. She realized, with some frustration, just how much animal protein people were actually consuming.

“As much as I believe in regenerative agriculture, there's just no way to sustainably eat meat every single night of the week,” she said. “So I started sneaking a lot of vegetables into my sausages.”

A woman who was working at a green market attached to Nicoletti's butcher shop would give her wilted produce at the end of the week. Accepting the challenge, Nicoletti would lay it all out like a puzzle and figure out what she could make with it.

“So, like, wilted carrots, and celery, onions, sad dill — that's matzo ball soup,” she said. “You know, bruised tomatoes and basil — chicken Parm.

“I had set out to make 40 pounds of sausages and, after I had mixed it all together, I weighed out the farce and it was, like, 70-something pounds. And I realized that I had essentially doubled my meat by adding vegetables to it.”

But in the sausage industry, she explained, “binders” and “fillers” have always been dirty words because historically people have used not-so-appetizing ingredients like hardtack and sawdust to make their meat stretch further.

Nicoletti started thinking to herself: What if we turned that on its head? What if she were to add good things to stretch this meat further with the intention of making high-quality, humanely raised meat available to more people?

In 2015, with her technicolor sausages in hand, Nicoletti helped open Foster Sundry, another butcher shop in Brooklyn, where the owner, Aaron Foster, gave her the liberty to “go crazy” and experiment with whatever popped into her head. With her newfound freedom, she was pumping out sausages in complex flavors she’d only dreamt of: pho (made with beef broth, garlic, ginger, scallions, basil, chilis and star anise), xiao long bao (pork broth, chicken, scallion, ginger, garlic, mirin, soy sauce and sesame oil) and many and many more.

Posting her creatively colored creations on Instagram, Nicoletti developed a large following. And that’s when the sausages really took off.

“I threw myself in fully,” she said “And I was making, like, 5,200 pounds a month of sausage with my hands. I didn't have any special equipment. I was hand mixing, hand stuffing everything. And I could not keep up. And so I started looking to scale up.”

The meat of the matter

After professionally butchering meat for over 10 years, Nicoletti wanted to expand her idea but she had never launched her own business and wasn't sure where to begin.

Would she open a small shop like her grandfather? Could she rent out a production facility?

Nicoletti knew she needed help. In early 2018, one of her friend's put her in touch with Erin Patinkin, a co-founder of the popular Brooklyn-based bakery Ovenly.

“So I reached out to her (Erin), and … within 20 minutes she was, like, ‘Yes, this is scalable. Yes, let's blow this through the roof,’” she said.

After Patinkin hopped aboard, the duo found their third co-founder and chief operating officer, Ariel Hauptman, who Nicoletti describes as an “operations genius.” Her job is to get the sausage made and ensure that it makes it onto the store shelves.

"Erin had actually tried to hire Ariel at Ovenly," she said. "And we immediately clicked."

But it wasn’t easy getting the product to market. First, she had to find a co-packer — a company that would be able manufacture and package her sausages in large quantities — but most of them were intimidated by the high percentage of fresh vegetables she was trying to pack into the sausages.

Between 2017 and 2018, she approached nearly 100 co-packers, asking for help. They all said no for various reasons but, according to Nicoletti, a big reason was because the science was too complicated: How large does this vegetable need to be diced? How long does it need to be mixed for? What can we add to hold some of the water from the vegetable?

In October 2018, a co-packer outside of Kansas City, Missouri, changed her business forever. Paradise Locker Meats, owned by father and son Mario and Lou Fantasma, said, “Sure, we’ll try it!”

“I believe it was the challenge,” Mario told TODAY. “We'd never done sausage with vegetables and meat combined at the amounts that she was looking for.”

Lou agreed: “We immediately saw the drive that she had, the passion she had."

Getting the meat to market

But getting the sausage made wasn't enough — she had to sell it, too.

"We had worked so incredibly hard and overcome so many obstacles just to get this produce made," said Nicoletti. "And then suddenly it was like, 'Oh man, now we have to convince people to actually buy them.'"

Luckily, Hauptman had navigated Whole Foods distribution at a previous job and got them an introduction.

And, in a twist of fate, the person they were speaking to at Whole Foods Global said he was already following her on Instagram — and a fan of her sausages.

"Cara went to Whole Foods, a very, very large, very well known, highly reputable company,” said Salett, beaming. “And they bought her product immediately. I can lie awake at night thinking how remarkable it is that she was able to achieve that. And I'm very proud of her.”

Seemore Meats & Veggies started shipping products nationwide in 2020 through Goldbelly and is available at Whole Foods in New York, northern New Jersey, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, Rhode Island, Connecticut, California, Hawaii, Nevada and Arizona.

But at $9.99 for a 4-sausage pack, Nicoletti recognizes that her product isn’t the cheapest item on the shelf. However, she’s working hard to make it more accessible without sacrificing quality, she said. “But, you know, $9.99 gets you 12 ounces of meat, and vegetables, lots of protein, all kinds of vitamins. And that's more of an option than, you know, $50 pasture raised pork shoulder.”

That’s the ultimate goal: to make it easier for people to eat well.

“I really want people to be able to just have a meal that they can put in a pan, and heat up, and it's nutritious, and it's delicious, and it's fast,” she said. “So that good meat doesn't have to be this laborious, complicated thing.”

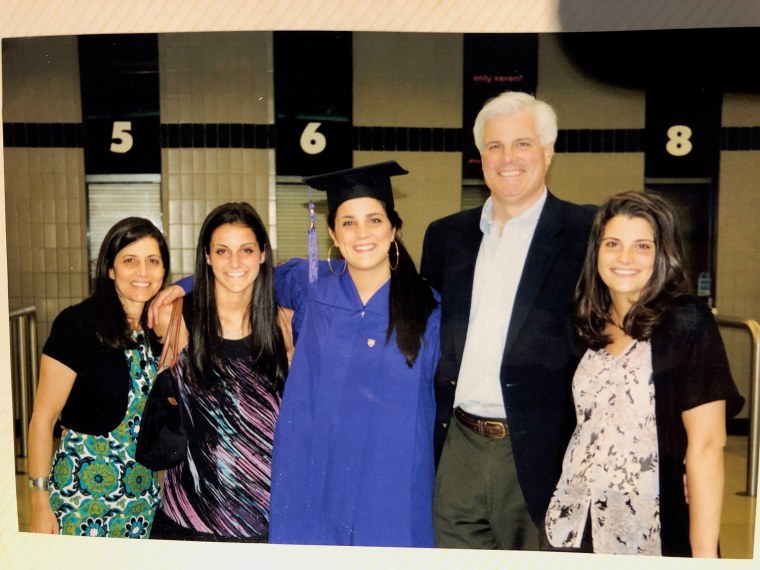

That mission has never been more important to her than now, with her sister Gemma’s recent cancer diagnosis.

In July, Gemma was diagnosed with a grade-three anaplastic astrocytoma, a rare, malignant brain tumor. She had her first surgery in October and her second in December.

“So all of it really coincided with building this business out,” said Nicoletti. “And that's been really complicated because Gemma is my hugest, biggest cheerleader, and she wants me to, you know, put this stuff out there about sausages. But it is a very strange thing to be, you know, Instagramming about your sausage company when these kinds of things are going on.”

An unintended silver lining, though, is that her sausages have actually been very helpful to her sister. Gemma was a vegan for a long time (she didn’t like to see what her grandfather was doing in the “smelly room”), but her doctors wanted her to try the trendy, high-protein, low-carb ketogenic diet to help with her seizures (the ketogenic diet was invented as a treatment for epilepsy was discovered in 1921 by Dr. Russel Wilder of the Mayo Clinic), and it’s helped her a lot.

But, as a practiced vegan, she was struggling to figure out what to eat.

“The sausages have been hugely helpful to her because they're just like little keto meals for her,” said Nicoletti. “So she eats them all the time.”

By naming the company after her grandfather, she wanted to make it clear that this business is all about honoring her family, who have been there for her through everything.

“This business isn’t just about me,” she said. “It’s about my family, supporting them and giving back to them.”

Bring on the competition!

Her product is on a crowded shelf now, competing with much bigger brands like Aidells (owned by Tyson Foods) and Applegate (owned by Hormel).

“Make no mistake, this was not an easy process, and I almost quit many, many, many times,” said Nicoletti. “I think the thing that kept me going was the fact that there are now people doing this, and getting it to market.”

“I knew that I was doing it ten years ago, and that people were sort of thinking I was crazy, and laughing at me. And now we're seeing these things on the shelves and I can't help but feel like I was part of getting that to be a thing.”

And now that she’s made it this far, Nicoletti wants to encourage other women to get into this field and make it so that “being the only one” isn’t their only value.

“I think the more of us that are in this industry the better,” she said. “And we can all exist at the same time and support each other."

Butchery is a difficult job — with very little financial payoff, Nicoletti is quick to note — but she wouldn’t have done anything differently. Because she’s here now.

“Butchery helped me with self-confidence, body image, physical and emotional strength,” she said. “I want women to know that this is an option for them.”