Wine, when you begin to analyze it, has many component parts. The fruit, of course, is paramount; it's the soul of a wine and tells us more about a wine's pedigree than anything else. Memorable wine (it can be relatively inexpensive) has vivid, well-defined fruit tastes — blackberry and plum in cabernet sauvignon; apple, pear and tropical fruit notes in many chardonnays; accents of lemon, lime and orange in any number of white wines, to name just a few common tastes and aromas.

Then, depending on the variety, there are suggestions of spices and herbs as well as vanilla (in some whites) and chocolate (in some reds). Oak aging contributes to these tastes and also gives American chardonnay, for example, its typical buttery quality, whether you like it or not.

When young, some distinguished red wines, such as cabernet sauvignon and nebbiolo (the great Italian grape of Barolo), show varying amounts of tannin, the remnants of the solids of the grapes that give red wines "structure" and make them "chewy" and sometimes harsh before they soften with age, a process that can take from a few years to more than a decade, as with great Bordeaux.

For me, one of the more subtle and interesting components of wine, especially whites, is minerality, which, as the word suggests, is the presence of minerals. They come from deep in the soil as the vines suck up water that carries nutrients and minerals to the grapes. But how do you detect them? There are a few clues.

When you breathe in certain white wines, you may notice a smell, separate from the fruit, that will remind you of wet rock, like slate or granite or limestone. In the mouth there's a bit of texture — again, a slightly "chewy" quality.

Now, it's important to realize that not all wines have this distinction. You're less likely to find it in cheaper, mass-produced wines than in smaller-production wines from choice vineyard areas whose soil is rich in minerals. But price itself isn't always a barometer. It's not hard to find excellent, mineral-laden wines for $10 to $20, such as muscadets and many sauvignon blancs and chenin blancs from France's Loire Valley; rieslings from Germany; pinot grigios and other whites from northern Italy and chardonnays from the Mâcon area of Burgundy, among others.

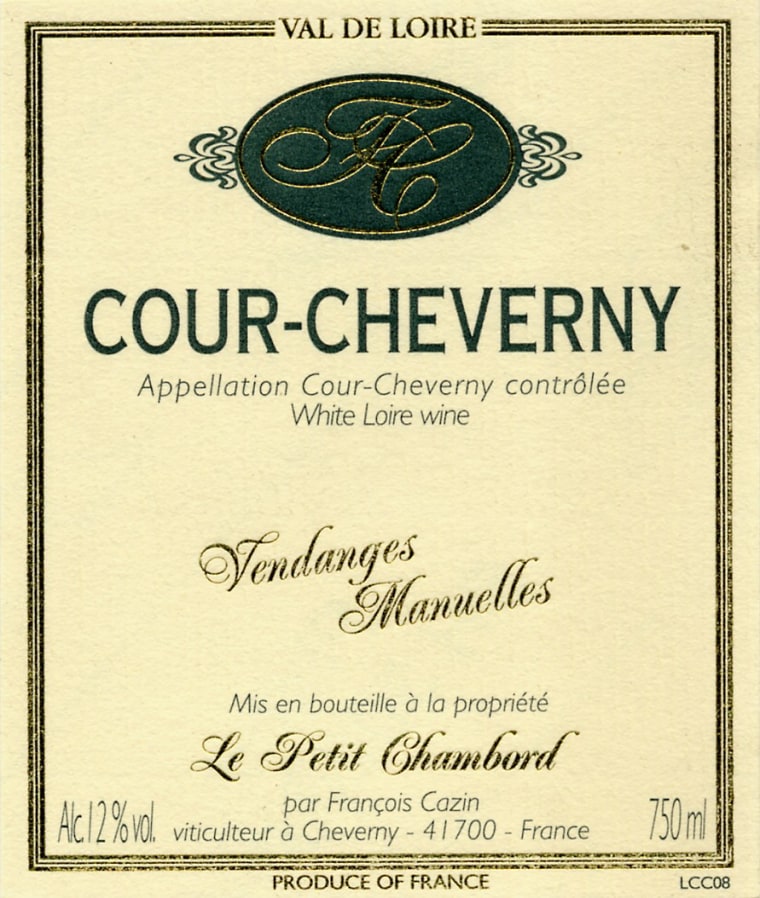

Two wines that I tasted recently were striking for their mineral presence. The first was François Cazin's 2002 Cour-Cheverny from the town of Cheverny in the Touraine area of the Loire Valley. The wine is made entirely from romarintin, a local variety that is grown in the area's clay, limestone and silica soils, which, of course, is where the minerals come from. They combine with notes of melon, apricot and citrus to form a crisp, refreshing and complex wine for about $13.50 that will pair well with many fish dishes. Louis/Dressner Selections is the importer ().

The second wine was Domaine Weinbach's 2002 Sylvaner from France's Alsace region, which is just next door to Germany. Here, the little-known sylvaner grape produces a steely dry and herbal wine with touches of apple and honey. It matched well with delicately deep-fried shrimp with a sauce of finely chopped sweet and spicy tomatoes. This sophisticated wine with its notes of minerals, flowers and white pepper, reminded me of a lighter version of Alsatian gewürztraminer, the powerfully herbal wine for which the region is perhaps best known. It has a suggested price of $22.50 and is imported by Michael Skurnik Wines ().

For me, the beauty of wine is how it connects us to the land, to a specific, unique place that shows its signature through the grapes. Minerals are a vital and fascinating part of that connection.

Edward Deitch's wine column appears Wednesdays. He welcomes comments from readers. Write to him at EdwardDeitch