When folks think about Baltimore's food scene, the first thing that comes to mind is probably blue crab. Many locals have been eating tender, sweet crab meat from the Chesapeake Bay since they were old enough to chew. To discover more about one of the city's most iconic dishes, the crab cake, Al Roker took a culinary adventure through the city's eateries and took a deeper dive into the history behind those who have been catching crabs for generations to get to know the families keeping the iconic crab dish's legendary status alive today.

Like many foods, the origin of the crab cake is a hotly debated topic. But one thing many Marylanders do know is that Faidley's Seafood, a family-owned institution that's been serving crab cakes for over 130 years, is one of the best places to try the local catch.

It takes a village to make a crab cake

"People from all around the world come here to Baltimore just to grab a bite of the famous Faidley’s crab cake," Al says in his new TODAY All Day series "Family Style," which premieres Wednesday. "It’s made from fresh Maryland crab and family love."

Faidley’s has been in Nancy Faidley Devine’s family for four generations. She created her own crab cake recipe in 1987 and told TODAY she hasn't changed it since. Her secrets include using crushed saltines instead of breadcrumbs, which bind the crab to a creamy "magic sauce." The crab cakes at Faidley's are deep fried in soybean oil and then served up with an array of sides including macaroni and cheese, potato salad and coleslaw.

"I watch people for the fist time putting it in their mouth and they say, 'Oh my God.' And they're standing at a table in a market," Faidley Devine told Al. "They're not sitting down to a white table cloth and having someone serve it on a silver platter. It's on a paper plate, but it belongs on a silver platter."

One of the most lovable parts about Faidley's is that its core menu has stayed the same for decades — even Al recalled the iconic crab cake tasting exactly as it did when he first visited 26 years ago.

"I think that people are astonished to see my parents at 84 and 89 still working,” Faidley Devine’s daughter, Damye Hahn, told TODAY. “People ask her for autograph, they ask her for her picture, they ask her to hold their babies ... It’s really fun.”

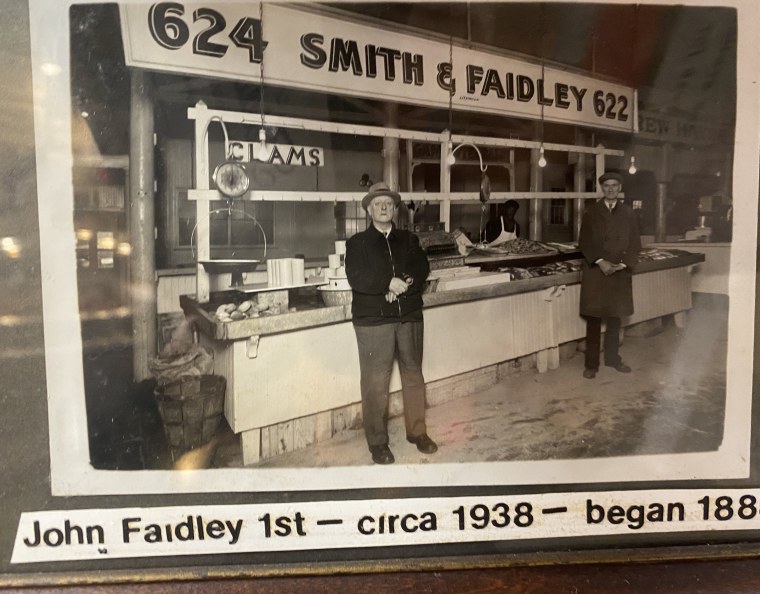

Faidley’s business started in 1886 when John W. Faidley, Sr. opened a seafood stall at the very same location the restaurant stands today in Baltimore's historic Lexington Market. While Faidley Devine and her husband still love coming into work, Hahn made the unexpected decision to take over the business at the onset of the pandemic in March of 2020, knowing the best thing to do was to keep her parents home and safe.

“He (her father) said, ‘Damye, do whatever you do, whatever you can to make payroll ... Just make sure that we don't have to lay anybody off. I don't wanna lay anybody off. I don't want anybody to lose their job,'" Hahn told Al, holding back tears. "And we did it.”

Faidley's isn't just a family-owned business, it's also a business run by families. Faidley's current staff includes multiple generations of employees — including fathers and sons, mothers and daughters. Many began working decades ago and continue the legacy of shelling, cooking and serving crab with their grown children.

The folks at Faidley's are just some of the many hard working people that make Baltimore famous for its crab. While tourists and locals flock to the city's restaurants to savor crab crakes on their plates, none of it would be possible without the men and women who have worked the Chesapeake Bay waters for generations.

Black watermen of the Chesapeake Bay

Since the 1800s, African American watermen (also known as "Black Jacks,") have been fishing for crabs and other seafood in the Chesapeake Bay. At a time when many of the nation's Black men and women were still enslaved in southern U.S., many Black Jacks were given "Seaman Protection Certificates," which, according to the Talbot Historical Society, gave them status as American citizens and allowed them to earn legal wages. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, these skilled fisherman caught and processed seafood like oysters and crab alongside their white counterparts and became integral to the local economy.

Captain Tyrone Meredith is a fourth generation waterman who learned to crab from his father. His grandfather and great-grandfather also fished in the bay.

"We've been here ever since the 1860s, making a living, working on the Chesapeake Bay," Meredith told TODAY.

Meredith's father, Captain Eldridge Meredith, became just the fifth Black man to be named Admiral of the Chesapeake Bay, a prestigious award bestowed by the governor and recommended by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

Today, the Black Jacks' trade is dwindling. One of the last generations of Black watermen making his living solely from crabbing is 75-year-old Lewis Carter, who began working when he was 15.

"Back when I started, it was plenty of Black watermen. But they died out and the younger ones never taken their place," Carter said. "In one way, it makes me feel bad, you know?" Today, Carter estimates that there are fewer than a dozen Black watermen on the bay.

When Meredith was a teenager, he could catch 50 bushels of crabs per day. Now he can only catch two or three bushels. Still, the captain isn't ready to give up life on the sea. Though crabbing is not as lucrative, he still runs Chesapeake Bay fishing charters through his own company and provides educational tours about the watermen's history to keep the memory of his ancestors alive.

A new generation takes on tradition

While younger generations of watermen may have left the waters to search for better job prospects positions on land, there is no shortage of new life in Baltimore's culinary scene today. New chefs in the city have emerged to honor the crab in different ways. Among them is chef Alex Perez, who owns the popular new restaurant Papi Cuisine.

"I grew up watching my grandma cook a lot. I started pretty much combining the foods that I learned to cook from my grandmother with the foods I learned to cook from my father," Perez, who was born and raised in Baltimore, told TODAY.

Eight years ago, Perez began operating a catering business from his grandmother's kitchen. Though he struggled initially, he never gave up on pursuing his dream of opening a restaurant of his own one day.

In February 2020, Perez's dream finally came true and he opened Papi Cuisine, an eatery inspired by his Afro-Latino heritage. But that dream quickly morphed into an unprecedented challenge amid the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Like nearly every restaurant across country, Perez had to quickly pivot and switched to focus his business on takeout orders. Though the brick-and-mortar location had only been open for a few weeks, Papi Cuisine had cars lined up for blocks, which Perez credits in large part to the community support that rallied around one of Baltimore's native sons.

The other reason? The food, of course. Perez is best known for his signature dish — a truly modern, portable take on a Baltimore classic: crab cake egg rolls. Though the chef admits he wasn't the first to stuff jumbo lump crab into an egg roll wrapper and deep fry it, he thinks he's perfected the recipe with the perfect blend of seasonings, a little cheddar cheese and not one but two dipping sauces.

With the restaurant's signature warhead sauce and house-made aioli, Perez's egg rolls take a timeless tradition and turn it into a handheld street food. It's crispy on the outside, full of tender crab on the inside, all bursting with vibrantly spicy and tangy flavors.

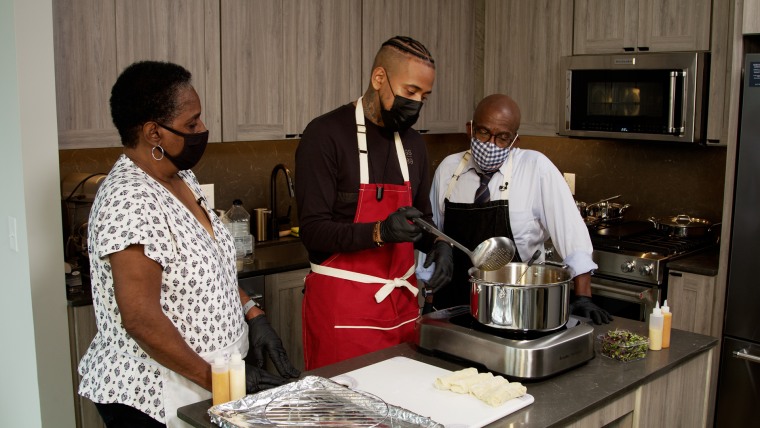

"Wow. Really, that is great," Al said after taking a bite of his first crab cake egg roll he made with Perez and his grandmother, Gloria. "And the sauce is fantastic."

Whether it's served in a traditional crab cake, deep fried in an egg roll or enjoyed freshly steamed, spiced with Old Bay and served on some newspaper with a mallet, crab is as essential to Baltimore's culture as it is to its cuisine. While it's hard to choose between old and new recipes when it comes to a crab cake, one thing is for certain: Food tastes better when you eat it with family.

On October 27, catch "Family Style with Al Roker" at 11 am ET on TODAY All Day.