IE 11 is not supported. For an optimal experience visit our site on another browser.

Real Estate

The Clarks: An American story of wealth, scandal, mystery

Why are the mansions of one of America’s richest women sitting vacant? Click to follow this photo narrative of the reclusive Huguette Clark and her father, William Andrews Clark, the "Paris millionaire senator." Where is Huguette Clark? And what will become of her fortune?

/ 48 PHOTOS

By Bill Dedman, NBC News. Why are the mansions of one of America’s wealthiest women sitting vacant? Huguette Clark's father, the copper king and "Paris millionaire senator," was the second richest American — or first, neck and neck with Rockefeller. Huguette, 103, has no children. Where is she? And what will become of her fortune?

Huguette with one of her prized dolls around 1910. Doll collecting became a lifelong passion for the reclusive heiress.

—

She doesn't live here. The mysterious Clark estate in Santa Barbara, Calif., has been empty since 1963. Named Bellosguardo for its "beautiful view" of the Pacific, it's worth more than $100 million, a 21,666-square-foot house on 23 acres. Caretakers have labored at the Clark estate for generations — and not met Huguette Clark.

Bellosguardo, the Clark family estate in Santa Barbara, Calif.

—

She also doesn't live here. In 1951, Huguette Clark bought this home in New Canaan, Conn. She named it Le Beau Château, or "beautiful country house." And she never spent a night in it. Now her 13,459-square-foot home, with 52 wooded acres, is for sale for $24 million, marked down from $34 million. Taxes are $161,000 a year.

Absolute privacy of Le Beau Château, the Clark estate in New Canaan, Conn. The house at 104 Dan's Highway cannot be seen from the road. Nearby residents of New Canaan include singer-songwriter Paul Simon and pianist-actor Harry Connick, Jr. It's an hour's drive to Manhattan.

—

And she doesn't seem to live here, though her belongings are here. The largest spread on New York's Fifth Avenue is her three apartments at 72nd Street overlooking Central Park. She has 42 rooms and 15,000 square feet. That's all the 8th floor and half the 12th, worth more than $50 million. The building staff have seen Huguette ("u-GET") few times in 30 years.

907 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

— Bill Dedman / msnbc.com

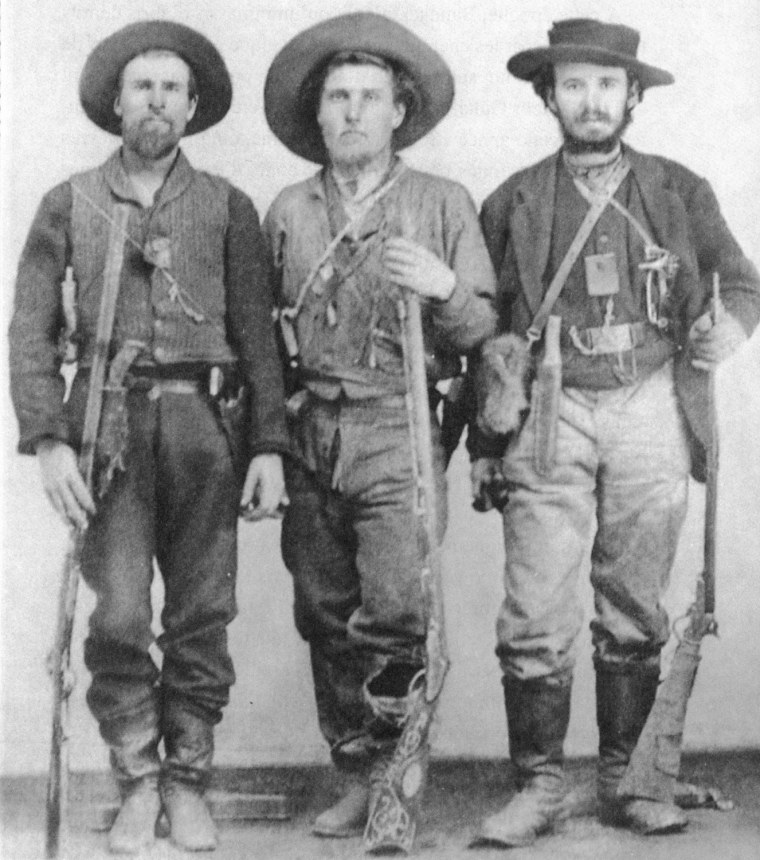

Where did such wealth come from? It started with hard work, ingenuity and unfettered ambition. One of these miners in 1863 in Bannack, Mont., would, by the end of the century, own banks, railroads, timber, newspapers, sugar, coffee, oil, gold, silver, copper — seemingly unending veins of copper. He's on the right, William Andrews Clark, Huguette's father.

William Andrews Clark, right, with fellow miners at Bannack, Mont., c. 1862.

— From \"Le Sénateur Qui Aimait La France,\" 2005, by André Baeyens

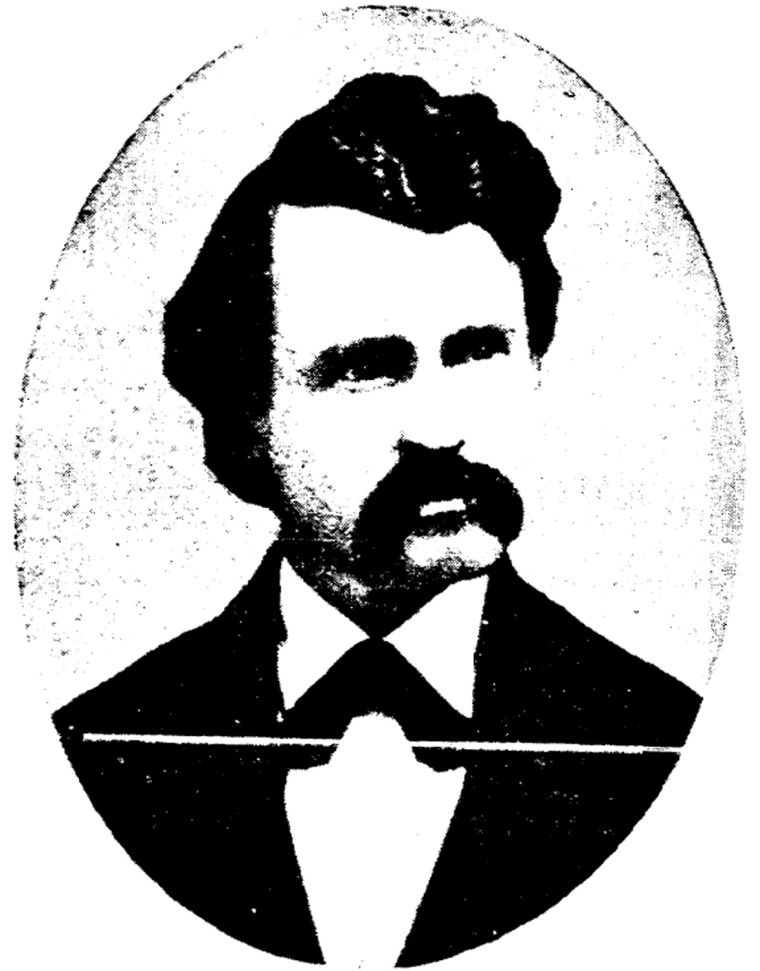

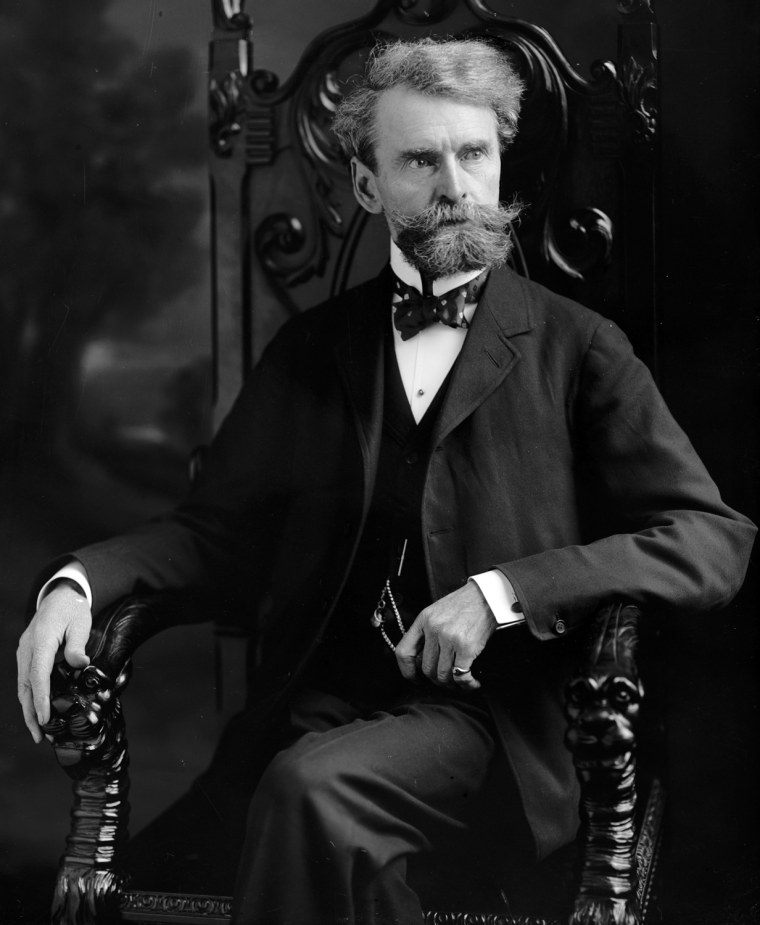

Born in a log cabin in Pennsylvania in 1839, of Scotch-Irish and French Huguenot immigrants, Clark stood 5 feet 8½, with fastidiously tended whiskers, unruly red hair, and cold blue eyes. A contemporary wrote, "There is craft in his stereotyped smile and icicles in his handshake. He is about as magnetic as last year's bird's nest."

William Andrews Clark.

—

After two years panning for gold, Clark turned to selling goods he hauled by wagon through the Rockies. He bought eggs at 20 cents a dozen, marketing them for $3 a dozen to miners for a brandy eggnog called Tom and Jerry. He took a year back East to study geology at Columbia University, then returned to Montana, to Butte's "Richest Hill on Earth."

— Lewis Pub. Co., Chicago

Clark made his greatest fortune in the Southwest. His United Verde copper mine, in Jerome, Ariz., yielded a profit of $400,000 a month, or in today's dollars, $10 million a month. The trading post of Las Vegas was a stop on his rail line. Here he speaks to a crowd in Las Vegas from his Pullman car in 1905. Las Vegas today is in Clark County, named for him.

William Andrews Clark in Las Vegas, the seat of Clark County, named for him. Then a United States senator, Clark spoke to a crowd in Las Vegas from his private Pullman railroad car in 1905. Not for reuse without permission of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

— ![Marcus Daly

[no date]](https://media-cldnry.s-nbcnews.com/image/upload/t_fit-760w,f_auto,q_auto:best/MSNBC/Components/Slideshows/_production/ss-100205-Clark-family/daly_clark.jpg)

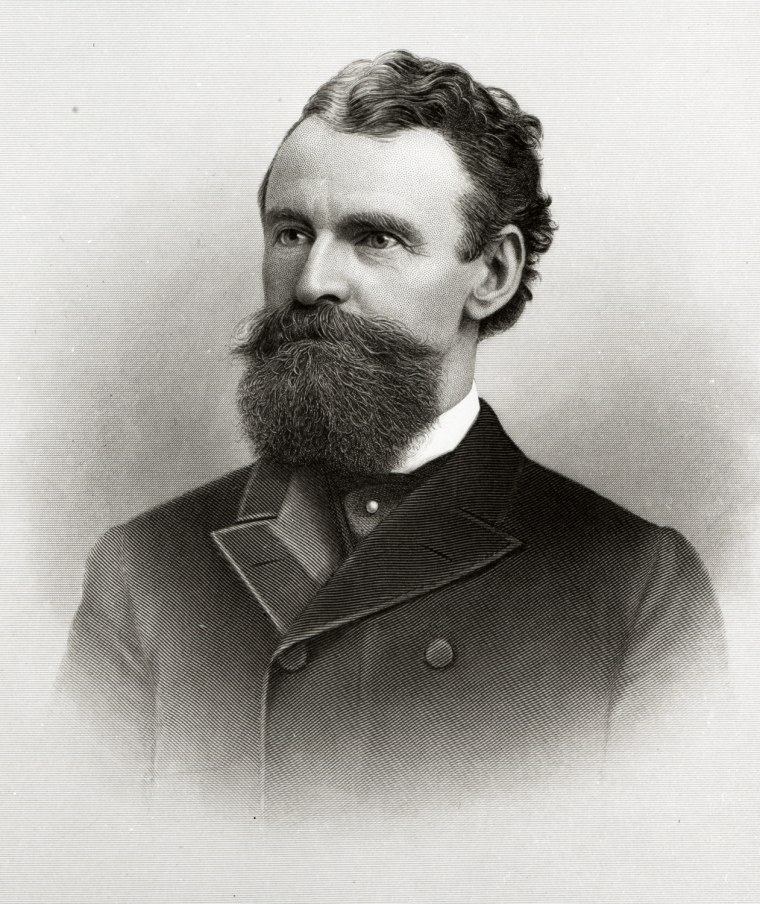

Clark's desire was a title: Senator Clark. Montana denied him time after time, a battle called the War of the Copper Kings. Who knows how a feud flared between Democrats: Marcus Daly, left, a Catholic who loved racehorses, and Clark, a Presbyterian who loved art. Legislators picked senators; newspapers made legislators; all were for sale.

Marcus Daly

[no date]

— Photograph By Davis Sandford

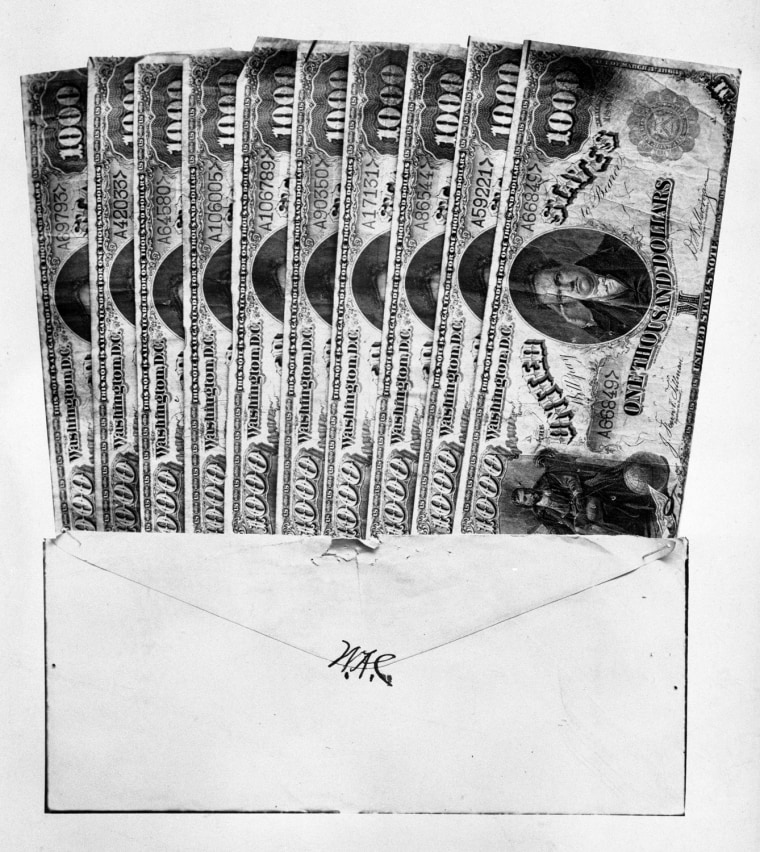

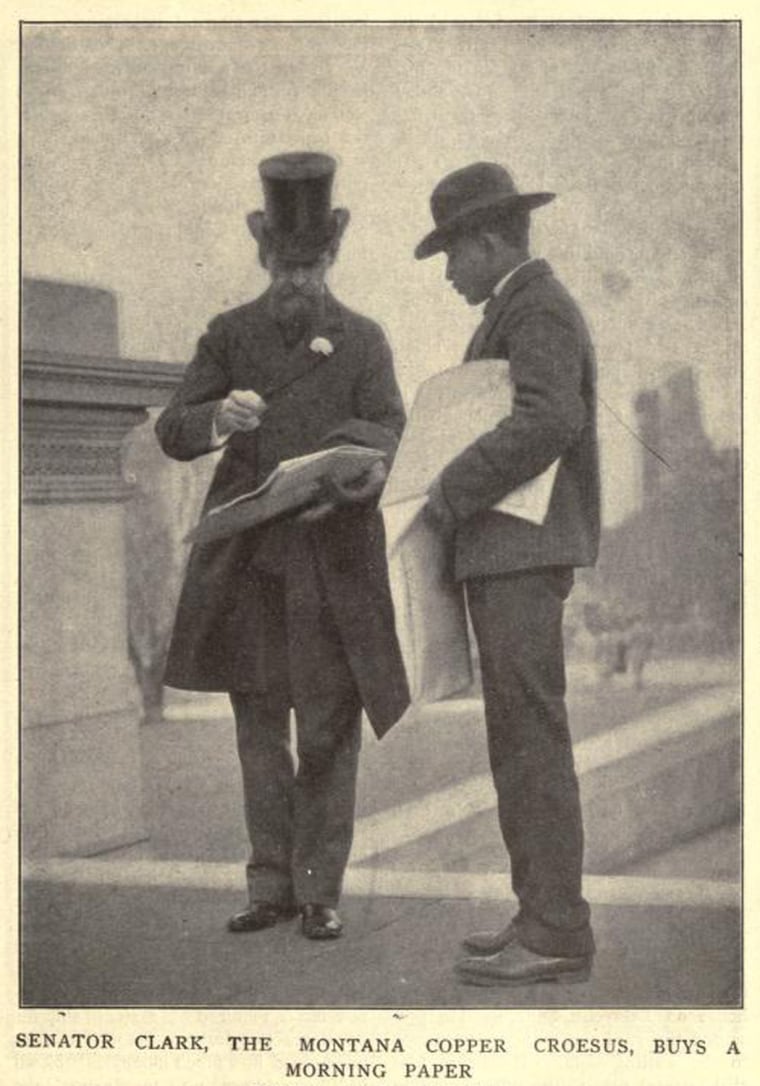

An aide said, "We'll put the old man in the Senate, or the poorhouse." Clark was elected in 1899, but $1,000 bills turned up in envelopes. He had to resign. Clark said publicly, "I propose to leave to my children a legacy, worth more than gold, that of an unblemished name." Privately he said, "I never bought a man who wasn't for sale."

Thousand dollar bills in an envelope bearing the initials \"W.A.C.,\" supposedly used to bribe Montana legislators to send William Andrews Clark to the U.S. Senate in 1899. Not for re-use without permission of the Montana Historical Society.

—

Clark's men tried one more audacity: On the day he resigned, they tricked the governor into traveling outside Montana. His lieutenant filled the vacancy — with Clark! When the governor returned, again Clark was out. Finally, he was elected in 1901. Though he retired after one term, for the rest of his life he insisted on being "Senator Clark."

Senator William Andrews Clark of Montana.

— Clinedinst

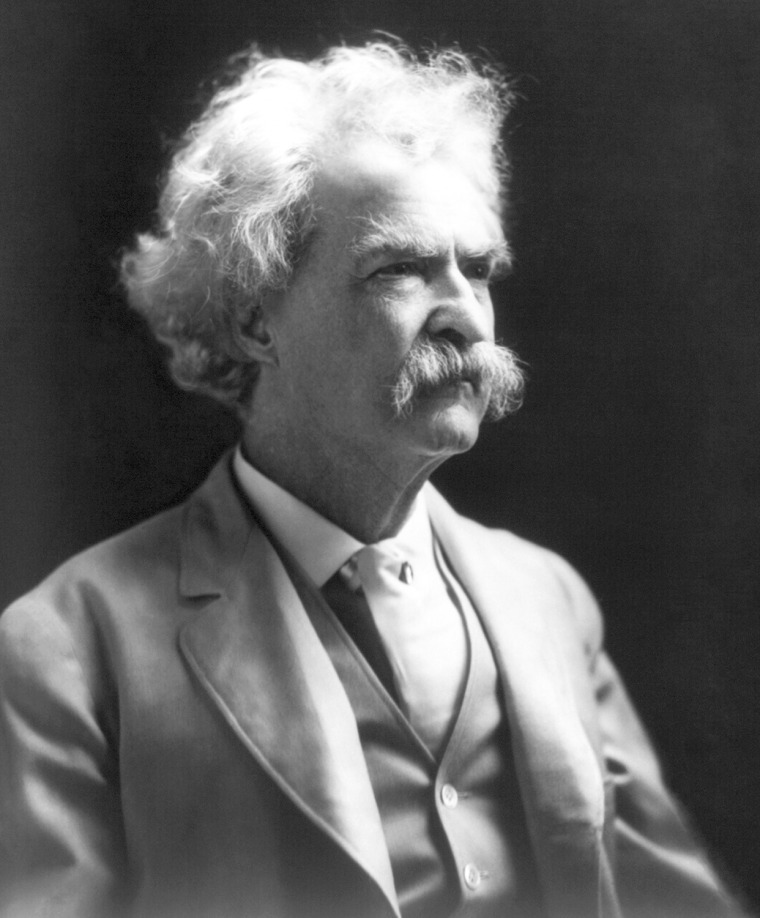

Mark Twain had a few other names for Senator Clark. "He is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped to send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a chain and ball on his legs."

Mark Twain

— Library Of Congress

Clark's first wife, Kate, died in 1893, leaving him four grown children. In 1904, while in the Senate, Clark announced that he had taken a second wife in France three years earlier, and that the couple already had a 2-year-old daughter. At the time of the supposed marriage, he was 62, and wife Anna was 23. No proof of the wedding date has been found.

The Butte Miner, 1904.

—

His new wife, Anna Eugenia La Chapelle, had been Clark's ward. She came to him as a teenager for support. Clark sent her from Butte to boarding school, then to Paris, where she studied the harp. He visited by steamship. They had two daughters: Andrée, born in 1902 in Spain, and Huguette in 1906 in Paris, where they lived with Anna.

Anna La Chapelle Clark, 1904.

—

"THEY'RE MARRIED AND HAVE A BABY," thundered Daly's opposition paper. All this was news to Clark's children from his first marriage, who were older than his young wife. One older daughter wrote that, while she was "greatly grieved and dreadfully disappointed, we must all stand by our dear father."

The Anaconda Standard, 1904, announcing the marriage of Sen. William Andrews Clark.

—

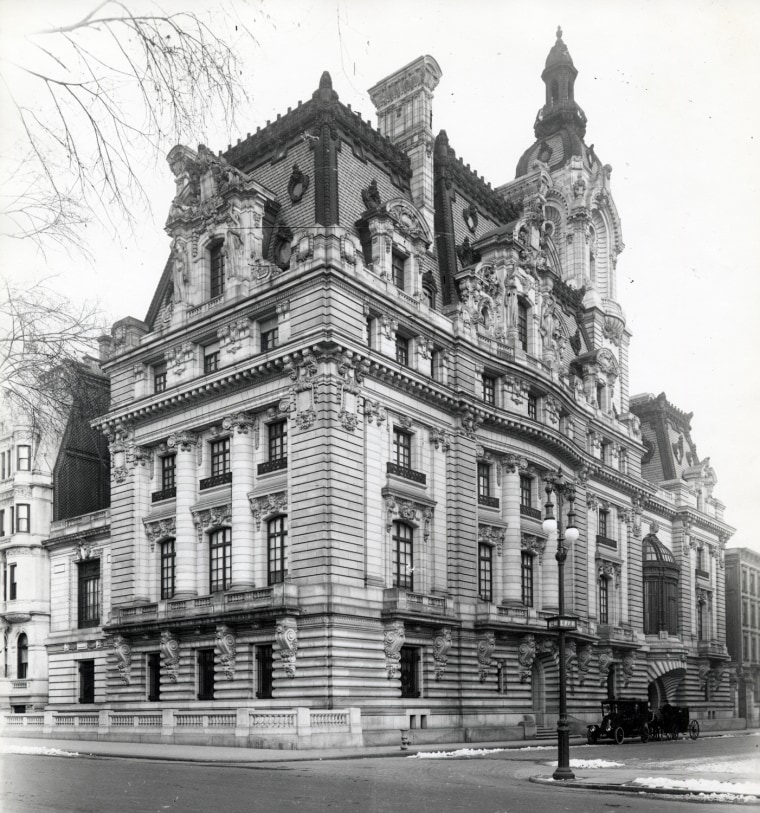

After he left the Senate, Clark moved his young wife and daughters into this Beaux-Arts house he built at Fifth Avenue and 77th Street in New York. It had 121 rooms, four art galleries, Turkish baths, a vaulted rotunda 36 feet high, and its own railroad line to bring in coal. All for a family of four. It was known as "Clark's Folly."

The home of Sen. William Andrews Clark at Fifth Avenue and 77th Street, which stood from approximately 1907 to 1927. Not for re-use without permission of The New-York Historical Society.

—

Clark spent as much as $7 million on the house, about three times what it would later cost to build Yankee Stadium. The mansion's treasures included this Louis XVI salon, a marble statue of Eve by Rodin, oak ceilings from Sherwood Forest, and the grandest American collection of European paintings, lace and tapestries.

A gilded room in the Clark mansion on Fifth Avenue, the Salon Doré, now at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.

—

Clark hosted organ recitals, so his neighbors on Millionaire's Row could see his paintings by Degas, Rubens, Rembrandt, Titian, van Dyck, Gainsborough, Cazin, Rousseau. Once his chosen artworks were installed in the house, Clark bought few more. If he acquired any more paintings, he wrote, he would have to remove something.

Edgar Degas, \"The Dance Class,\" c. 1873, oil on canvas, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, William A. Clark Collection.

—

Writer Wallace Irwin set it all to verse: "Senator Copper of Tonopah Ditch made a clean billion in minin' and sich. Hiked for New York, where his money he blew, bildin' a palace on Fift' Avenoo. 'How,' says the Senator, 'kin I look proudest? Build me a house that'll holler the loudest. None of your slab-sided, plain mossyleums! Gimme the treasures of art ...

Detail of the William Andrews Clark house on Fifth Avenue. Not for reuse without permission of the New-York Historical Society.

—

... an' museums! Build it new-fangled, scalloped and angled, fine like a weddin' cake garnished with pills. Gents, do your duty, trot out your beauty. Gimme my money's worth, I'll pay the bills.' Pillars Ionic, eaves Babylonic, doors cut in scallops resemblin' a shell. Roof was Egyptian, gables caniptian. Whole grand effect when completed was — hell."

One of the four art galleries in the William Andrews Clark mansion on Fifth Avenue.

—

Clark's wife was rarely seen in public. He wrote of Anna, "Mrs. Clark did not care for social distinction, nor the obligations that would entail upon my public life." In 1912, former Senator Clark, 73, and Anna, 34, walked in the Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue with Andrée, 9. Huguette, not pictured, was just 5, starting her collection of dolls from France.

The Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue, New York City, 1912, with Anna and former Sen. William Andrews Clark and their elder daughter, Andreé.

—

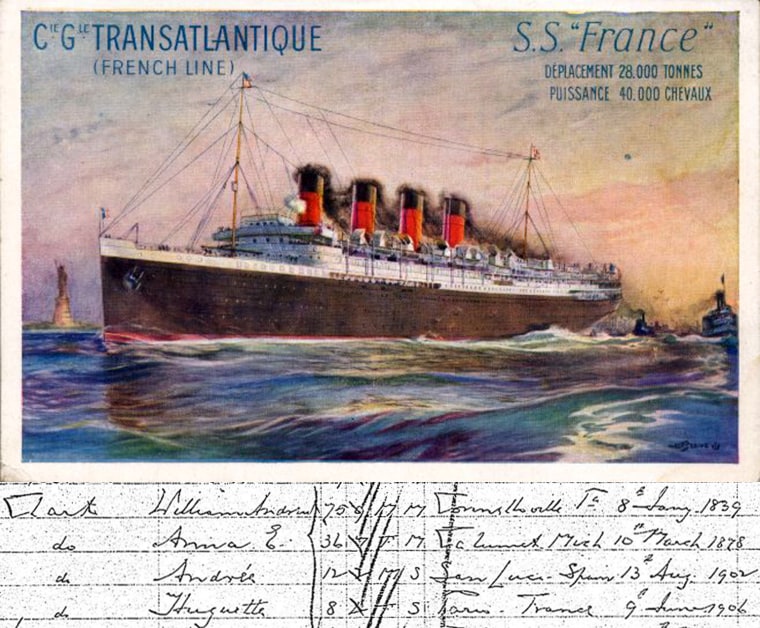

The Clark family traveled often to Paris. A ship's registry from 1914 sets birthdates for the family: William Andrews Clark, age 75, Connellsville, Pa., Jan. 8, 1839; Anna E., age 36, Calumet, Mich., March 10, 1878; Andrée, age 12, Spain, Aug. 13, 1902; and Huguette, age 8, Paris, June 9, 1906. At home, they had 10 servants and a French chef.

Ship's registry from 1914 trip to France by the Clark family. Postcard of the France, of the French line.

—

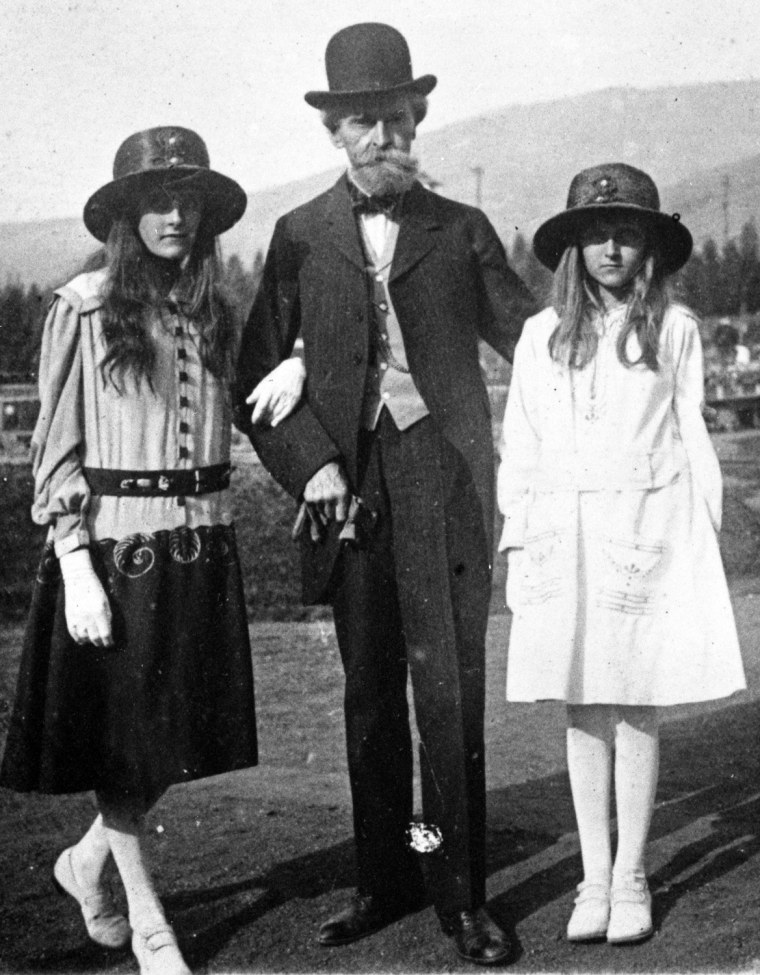

Clark and daughters visit Columbia Gardens, which he built in Butte. It was about 1917. Andrée (left) would be about 15, and Huguette 11. Clark was 78. In 1919, a week before her 17th birthday, Andrée died of meningitis. "When her sister died, it left a hole in her life," said Huguette's great-half-nephew through the first marriage, Ian Devine.

Copper king William Andrews Clark and his daughters, Andrée (left) and Huguette, in about 1915 at the Columbia Gardens amusement park, which he built for the people of Butte, Mont. Photo may not be re-used without written permission of MHS Research.

—

Through the '20s, society pages chronicled the debutante. "Miss Huguette Clark, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William Andrews Clark of 962 Fifth Avenue, entertained a party of girl friends yesterday at Sherry's." At Miss Spence's School for Girls, she learned politics; Isadora Duncan taught interpretive dance. Skirts had to be 3 inches below the knee.

The social outings of Huguette Clark (and her friends from the private Miss Spence's School) were chronicled in the society pages of The New York Times through the 1920s.

—

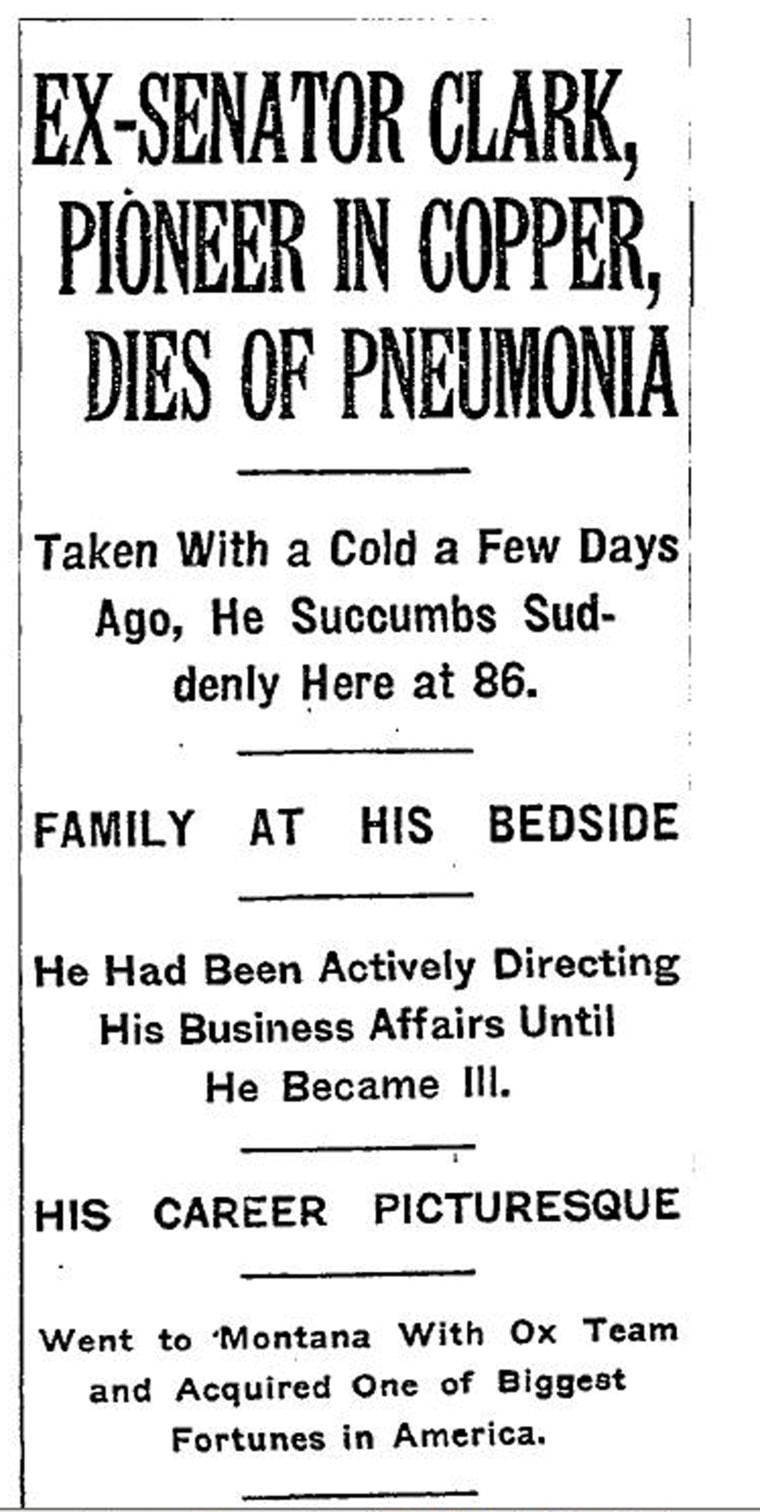

William Andrews Clark died in his house on Fifth Avenue on March 2, 1925, at age 86, with his wife and children by his side. He lay in honor in his own gallery, as his paintings looked down. President Coolidge sent flowers. Clark's will called for a "decent and Christian burial in accordance with my condition in life, without undue pomp or ceremony."

William Andrews Clark died of pneumonia in his house on Fifth Avenue on March 2, 1925, at age 86.

—

He was entombed, along with his first wife and Andrée, in this mausoleum at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. His neighbors now are Woolworth, Macy, Pulitzer — all better remembered. Clark left $350,000 to a Clark orphans home; $100,000 each to Clark kindergarten and Clarkdale, Ariz.; $25,000 to Clark women's home; $2,500 to his butler.

William Andrews Clark was entombed in this mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, N.Y.

— Bill Dedman

Clark had promised his daughters from his first marriage that Anna would not inherit the New York City mansion. It was sold in 1927 for less than half what it cost to build, and was torn down for apartments. Many other houses on Millionaire's Row fell, including the Astor and Vanderbilt palaces. The Gilded Age had passed.

Detail of the William Andrews Clark mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York.

—

Anna got the mansion in Santa Barbara and $2.5 million. The rest of Clark's estate — as much as $300 million, or $3.6 billion today — went to Huguette and the four older children, who soon cashed out all his businesses. Huguette, 18, also received an allowance for three years: up to $90,000 a year, equal to $1 million today.

William Andrews Clark was entombed in this mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, N.Y.

— Bill Dedman

To the art, Clark attached conditions. The Metropolitan Museum could have it, if it kept it all in a separate Clark gallery forever. The Met declined. The art went to his second choice, the Corcoran in D.C. His wife and daughters paid for a Clark wing to hold it. The museum found that some of the paintings were misattributed; this Corot was authentic.

Clark's will offered the bulk of his art colletion to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, just five blocks up Fifth Avenue, but only if the Met agreed to his conditions: It must house the art together, never breaking up the collection, and it must take all of it: the paintings, the statues, Italian Majolica ware from the 16th and 17th century, tapestries that hung in the billiard room, and lace. The Met said no. The art went to the second choice, the Corcoran in Washington, which built a wing (with Clark money) for the William A. Clark collection, across the street from the White House.

—

Clark bequeathed this advice as well: "The most essential elements of success in life are a purpose, increasing industry, temperate habits, scrupulous regard for one's word ... courteous manners, a generous regard for the rights of others, and, above all, integrity which admits of no qualification or variation."

William Andrews Clark was entombed in this mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, N.Y. Detail of the bronze door.

— Bill Dedman

Clark's descendants say he should be remembered as a Horatio Alger hero, a boy from a log cabin who conquered the worlds of finance, politics and art. "He lived exactly as he had planned," said André Baeyens, a great-grandson and diplomat, who wrote a book in French about the family. "He had a ferocious will to 'better my condition in life.'"

William Merritt Chase \"William Andrews Clark\" c. 1915 oil on canvas, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Gift of William A. Clark.

—

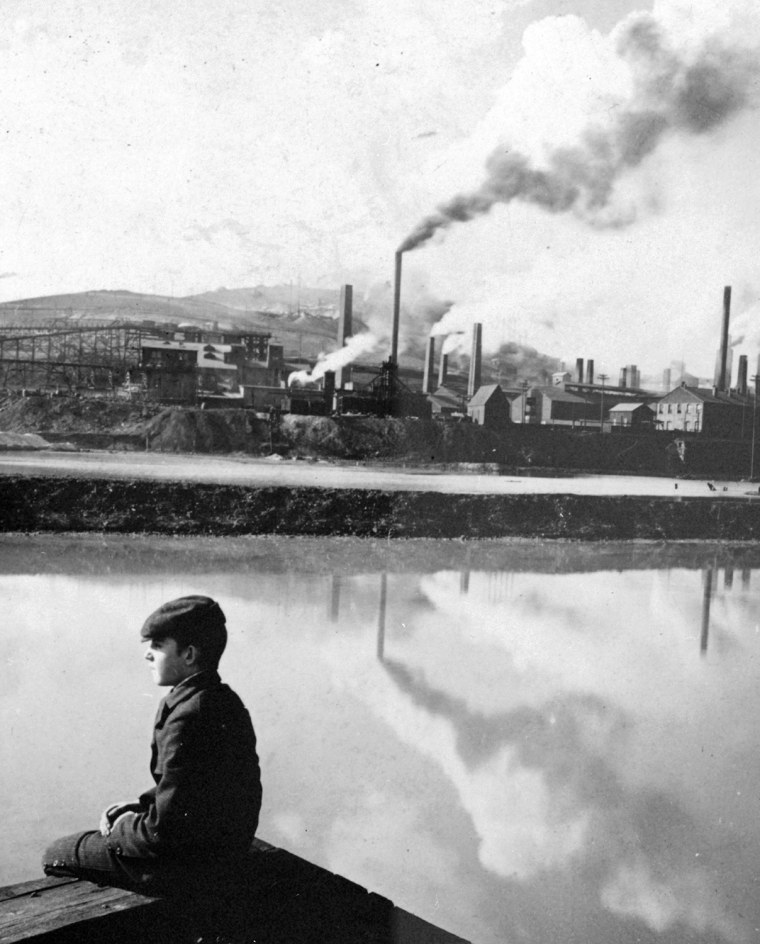

Bettering the condition of others wasn't his concern. Clark cut timber on federal land, and he benefitted from Arizona's "deportations" of union men who were kidnapped and driven out of state. Criticized for the sulfurous smoke and denuded landscape from his mines, he said, "Those who succeed us can well take care of themselves."

Boy and smelters at Butte, Mont., c. 1904.

—

"Robber barons," some historians call the tycoons of that era. Others prefer "industrial statesmen." Unlike Carnegie or Rockefeller, Clark left little charity, only corruption and extravagance. "Life was good to William A. Clark," wrote historian Michael Malone, "but due to his own excesses, history has been unkind."

William Andrews Clark.

—

After her father's death, Huguette Clark practiced music and art; seven paintings she created were shown at the Corcoran. In 1928, she became engaged to William Gower, a law student whose father had worked for Clark. "No married couple ever started married life under more brilliant auspices," The New York Herald said.

In 1928, Huguette Clark was married to William Gower, a law student and employee of her late father.

—

They were wed at Bellosguardo, the Clark home in Santa Barbara, on Aug. 18, 1928. The groom was 23, the bride 22. That year, Huguette donated $50,000 to the city to restore a salt pond behind the estate (top), called the Andrée Clark Bird Refuge. The couple moved into the elegant apartment on Fifth Avenue, with her mother in the same building.

Bellosguardo, the Clark estate on the Pacific in Santa Barbara. Huguette Clark gave the salt pond on the inland side to the city in memory of her sister, Andreé. She also donated 135 acres to the Girl Scouts for Camp Andreé Clark in Briarcliff Manor, N.Y.

—

It lasted two years. To establish Nevada residency for a divorce in 1930, she moved to Reno for the summer with her mother and six servants. With the papers signed, mother and daughter took a cruise to Hawaii, then returned to the apartment in New York.

The Gowers were divorced in 1930, after Huguette Clark Gower and her mother and six servants moved to Reno for an ignominious summer to establish residency for the divorce proceedings.

—

This is the last known photograph of Huguette, cornered by a photographer on the day of her divorce in August 1930. In 1931, an Irish nobleman denied reports that he would marry Huguette, then 24. She dropped her seat at the opera, and slipped from the society pages.

Mrs. Hugnette Clark Gower, daughter of the late Senator W.A. Gower of Montana, upper magnate, who was granted a divorce from William MacDonald Gower in Reno, Nevada August 11, 1930, on grounds of desertion. The couple were married in Santa Barbara, California in 1928, and separated more than a year ago. There are no children, and the decree was awarded with neither property alimony settlement. (AP Photo) Taken in 1930, this is the last known photo of Huguette Clark. Source: Associated Press.

—

After her mother died in 1963, Huguette stopped visiting Bellosguardo. Vintage cars remained in the garage. Paintings stayed on the walls, depicting her sister, Andrée, living well past her death at age 16, on into middle age. A caretaker's stepdaughter, Joan Pollard, recalls, "It was immaculate, as if someone had just left for the weekend."

Bellosguardo, the Clark family estate in Santa Barbara.

—

In 1964, Huguette gave 215 acres near Santa Barbara for Boy Scout camps. "These camps serve 4,000 kids a year," said Ron Walsh, a Scout executive. "She did a lot of people a lot of good through the years." In 2003, she sold this Renoir for $23.5 million. In 2007, the IRS placed a lien on her houses for $1 million in back taxes; it was paid quickly.

\"In the Roses,\" Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1882.

—

Huguette is trying to sell Le Beau Château, in wealthy New Canaan, Conn., an hour from New York City. She bought it in 1951, and added the wing at top right. It has 22 rooms, nine bedrooms, nine baths, 11 fireplaces, a wine cellar, trunk room, elevator, and walk-in vault. It has sat empty for 57 years, so the kitchens need updating.

Le Beau Château, the Clark estate in New Canaan, Ct.

—

The only residents on 52 acres are the caretaker and his son, in twin cottages, and wild turkeys and deer. The property is silent except for a waterfall. Her attorney put it on the market in 2005 at $34 million, now $24 million. Neighbors in this corner of town include Harry Connick Jr., Paul Simon, Glenn Beck and Brian Williams.

Le Beau Château, the Huguette Clark country house in New Canaan, Conn.

—

Why would someone buy such a retreat, and never use it, but hold on to it for half a century? Huguette's great-half-nephew, André Baeyens, said he was told by his mother that Huguette bought Le Beau Château as a sort of bomb shelter during the Cold War. "She wanted a place where she could get away from the horrors."

A grand staircase in Le Beau Château, the Clark estate in New Canaan, Conn.

—

"Huguette has always led a sort of reclusive life," said nephew Devine. "I think everybody's respected that. She wasn't just sitting in a room herself all her life. She had a small group of friends, confidants and assistants, very small, probably fewer than five people. Her world was always very small; when Anna died, it just became smaller."

Le Beau Château, the Huguette Clark estate in New Canaan, Conn.

—

Now 103, she may be in a nursing home or hospital. Relatives say they don't know, and fear that flowers and letters are discarded before they reach her. Her attorney, Wallace Bock, won't say. Devine said, "I think various family members have asked Mr. Bock for information, and he's always very respectful of his client and doesn't wish to reveal anything."

Le Beau Château, the Clark estate in New Canaan, Conn.

—

Facing Central Park with curtains drawn, her Fifth Avenue apartments contain her mother's harp and Huguette's French dollhouses. Only a few times in decades has the building's staff seen her, a thin woman retreating into the shadows. They say she's not there now. André Baeyens said of his aunt, "She's withdrawn from this world."

907 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

— Bill Dedman

Her eighth-floor apartments contain two galleries, seven bedrooms, rooms for nine servants. And her fortune? Where will it go? "The rest of the family would respect her decision," said nephew Devine. "But if she leaves it all to some sketchy cause that she has no close connection to, that would be of some concern."

Floorplan for 907 Fifth Avenue in New York.

—

Her attorney, Bock, said her hearing and eyesight have diminished with age — after all, she'll be 104 in June — but her mind is clear, and he receives instructions from her frequently by phone. He said he would not pass along a request for an interview. "She's a very private person. She doesn't care about publicity or reputation."

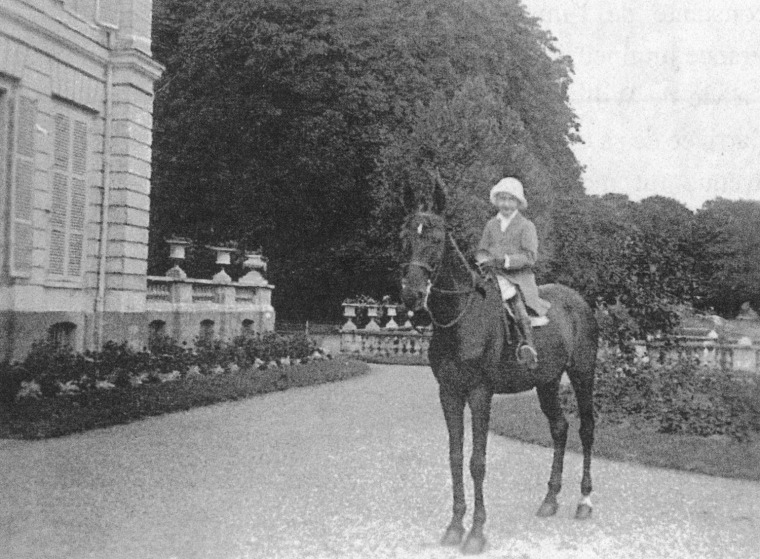

Huguette Clark as a child in France.

— Family photo, from \"Le Sénateur Qui Aimait La France,\" 2005, by André Baeyens

Tracing the lives of William Andrews Clark and his Huguette, we are left with mysteries. What does she remember of "Papa"? Is she well cared for? What will she leave to the world? "It's hard to find out what the real story was," said nephew Devine. "No one is alive — except for Huguette."

Huguette in Montana around 1923. Her father, Senator William A. Clark, made his fortune in Butte Copper Mining. Source: The Copper King Mansion.

— 1/48