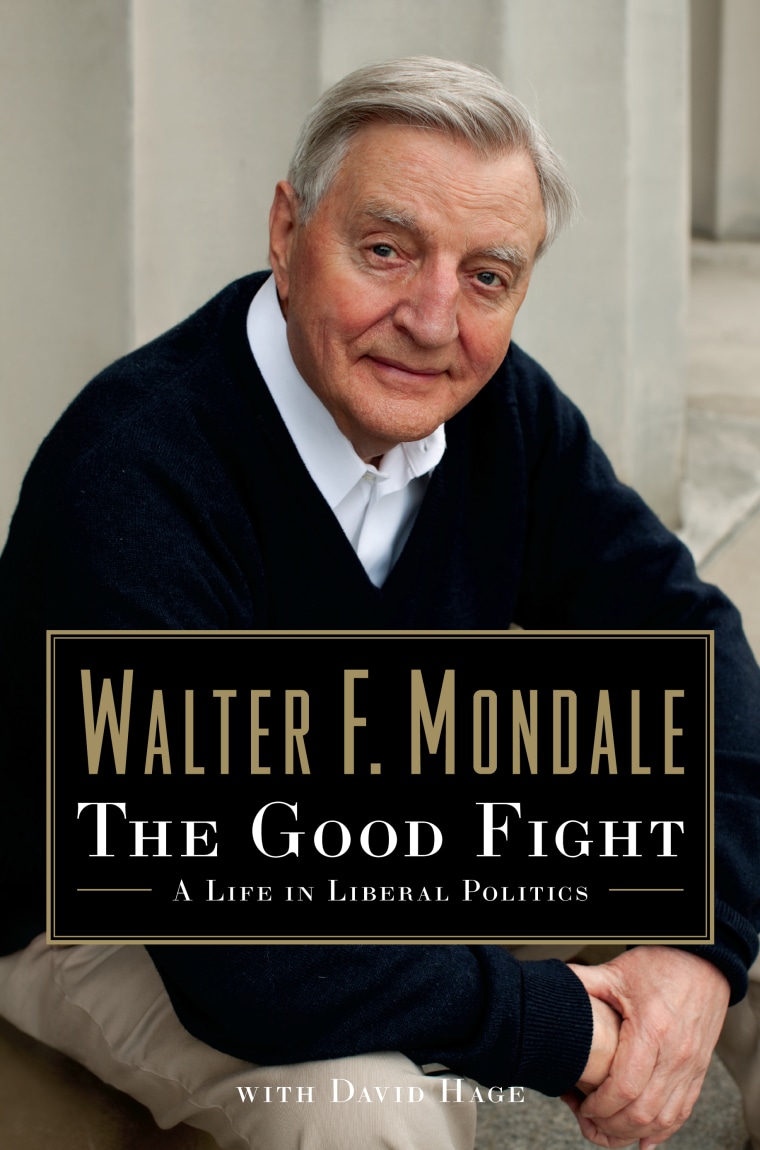

Walter Mondale, former Democratic vice president of the United States serving under President Jimmy Carter, charts in his new book, “The Good Fight: A Life in Liberal Politics,” the turmoil over the last 50 years, including weighing in on the Bush and Obama administrations through the lens of serving in the West Wing. An excerpt.

Introduction: Taking Care

Some years ago I was asked to give a lecture on political leadership at Rutgers University, and I found myself composing my remarks in the form of a letter to the next president. The year was 1987. Ronald Reagan, a popular president during his first term, had wandered into the swamp of Iran-Contra and was struggling to get back on solid ground with the American people. I had spent four years in the White House with Jimmy Carter, watching and working with the president at closer range than any other vice president in history, and I thought I knew something about leadership and integrity.

The advice I put in that letter was simple: Obey the law. Do your homework. Trust the American people. “The most cherished, mysterious, indefinable, but indispensable asset of the presidency is public trust," I wrote. “You don’t get a bank deposit, but it acts like a bank deposit. You have only so much. You’ve got to cherish, to protect, and to nurture it, because once it’s gone, you’re done.”

I pulled that letter out not long ago, after the election of Barack Obama. Not because I worried for Obama’s leadership, but because I have watched the ebb and flow of public trust for fifty years, and I know that, at turning points in our nation’s history, it can spell the difference between a society that slips backward into bitterness and frustration and a country that fulfills its greatest promise and highest ideals.

I came of age in a period when our country brimmed with hope and generosity. A confident people, following optimistic leaders, achieved a revolution in civil rights, declared a war on poverty, put astronauts in orbit, guaranteed health care for the elderly, reformed a bigoted and outdated immigration system, placed women on the path toward equality with men, and launched the movement known as environmentalism. I called it the “high tide” of American liberalism, and it left America a better, fairer nation.

But I also lived through a period of crippling cynicism and division.

I watched one remarkable president, Lyndon Johnson, self-destruct because he could not level with the American people about a war he was waging in their name. I saw a brilliant politician, Richard Nixon, leave the White House in disgrace because he succumbed to the temptations of deceit and the conviction that he was above the law. I spent a year of my Senate career investigating conspiracies by the CIA and FBI to spy on American citizens and subvert the law — then watched another administration three decades later systematically violate the law we wrote and the Constitution they had sworn to uphold. More times than I hoped, I watched the cynicism and dismay that set in when Americans lose trust in their own government.

This is not, perhaps, the homily that most Americans will expect from me. They will remember me as the Democrat who carried the banner of liberalism against tough odds in 1984 and lost to Ronald Reagan. They will remember me, if they have long memories, as the heir to a progressive political tradition that put civil rights and economic justice on center stage in American politics. I spent a career fighting for those ideals and I believe in them today as passionately as ever.

Those battles, however, also deepened my appreciation for the political tradition we inherited from our founders, a constitutional framework that enshrined accountability and the rule of law. Our founders understood the value of high aspirations. Did the world ever see a more audacious band of idealists than that small group of colonial farmers and frontier lawyers who presumed to convert the philosophy of Locke and Rousseau into a working democracy? But the founders also understood the frailties of democracy and the dangers of power, noting, in Madison’s famous phrase, that “men are not angels.”

The Constitution they wrote more than two centuries ago contains a brief phrase that legal scholars call the “take care” clause. It’s a simple sentence, contained in the passage setting out the duties of the three branches of government, enjoining the president to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

Time and again through my career I have taken inspiration from that phrase. In times that test our constitutional principles, the “take care” clause steers us back to the founders’ wisdom and reminds us that ours is, after all, a government of laws, not men. In times that fray our conscience and compassion, it reminds us of the obligation to sustain and nurture the magnificent experiment they left us.

Our founders understood that a decent society, a society that can endure and prosper, needs leaders who transcend the politics of the moment and pursue the nation’s long-term aspirations. These leaders will take care of the Constitution, understanding that they are only custodians of an ideal — stewards with a debt to their forbears and a duty to their heirs. They will take care of their fellow citizens — especially the poor and the disenfranchised — understanding that a society is stronger when everyone contributes. They will take care of our children, understanding that a wise society invests in the things that help its next generation succeed. They will take care of politics itself, governing with honor and generosity rather than ideology and fear, understanding that a nation decays when its people lose confidence in their own leaders. They will remember that the Constitution enjoins them to promote the common welfare as well as the blessings of liberty.

I entered politics young, impatient, and full of confidence that government could be used to better people’s lives. My faith has not dimmed. But I also came to understand that voters didn’t simply put us in office to write laws or correct the wrongs of the moment. They were asking us to safeguard the remarkable nation our founders left us and leave it better for our children. This book is an effort to explain that philosophy, to chronicle the battles that taught me these lessons, and to describe the evolution of a man and the country he was lucky enough to live in.

Excerpted from “The Good Fight: A Life in Liberal Politics” by Walter Mondale with David Hage. Copyright © 2010 by Walter Mondale with David Hage. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.