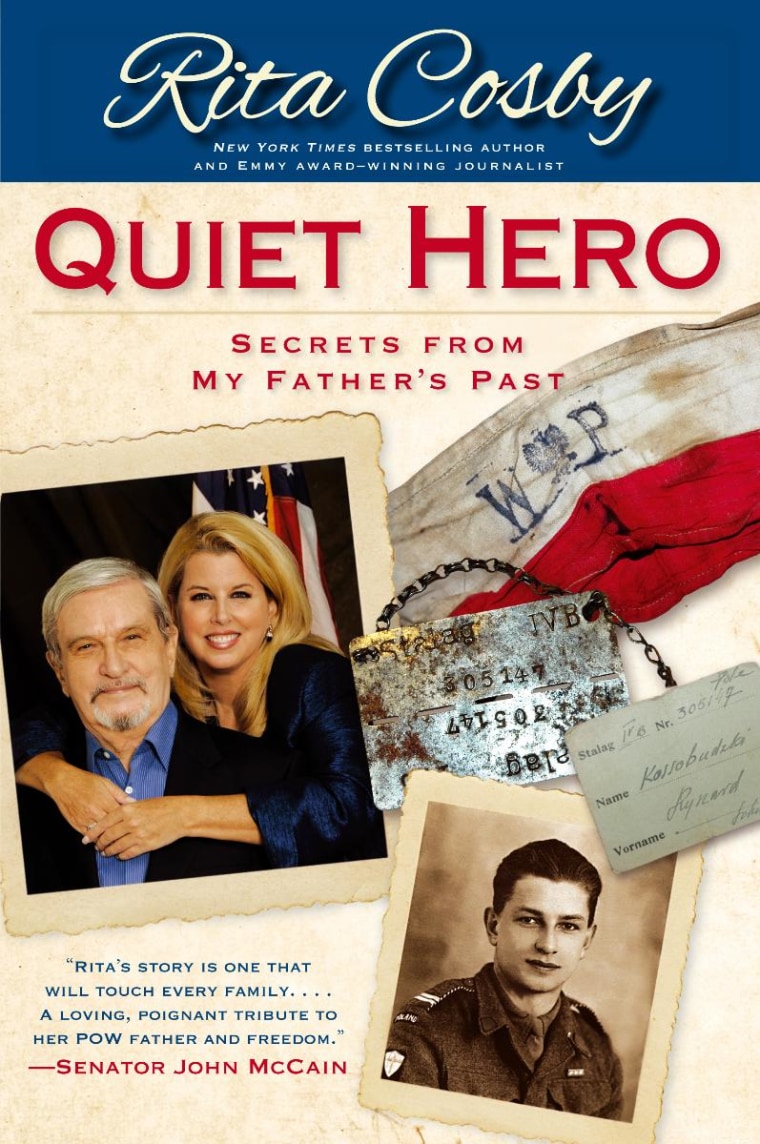

Journalist Rita Cosby grew up with a father who was often distant and nonresponsive, but she never imagined that he was once a 90-pound World War II POW. Read an excerpt from her book, “Quiet Hero: Secrets From My Father’s Past.”

Right between the eyes

In a few hours and two dozen questions, I had learned more about my father’s past than I had garnered in my entire life. As I sat next to him, I was forced to acknowledge that I never knew much about him at all, especially about his formative years. Is this normal in parent-child relationships? Do other children not know much about their own parents’ early years, the time “pre-me”?

And deeper still, do other children know anything of their parents’ triumphs, their tragedies, their fears? I had found the key to a locked chest of my father’s secrets, and perhaps to myself. He was talking and I was learning. Had I, for example, made a career of asking questions because my dad never answered mine? Did I become a journalist because my father left me always wanting to know more?

Am I so social because my dad never was, for fear of people asking him about his past, the history of his life? The one thing that’s certain is that I suddenly realized that by the time I was born, the harbored secrets of my dad’s life had already transformed him into someone else. Not “Ryszard Kossobudzki from war-ravaged Poland,” but “Richard Cosby, American citizen,” a man not unlike many in America’s “greatest generation”: disciplined fathers, who want their children to succeed, their wives to love them unquestioningly, and their employers to respect them. Men who go completely quiet about everything they saw or did during the war.

I’m astounded that he never discussed—not with me, not with his wife, not with his employers — that his youth was spent dodging death, fighting to save his country. Why had he built such huge walls around his past? Did he have something to hide? Or was this just the unspoken trauma of war?

I sat in his kitchen becoming conscious that the horrors of war must be like shadows dancing around his mind, never to be touched, but always there.

I suddenly realize I’m conducting the most important interview of my life.

“When did you actually start fighting, Dad?” I ask.

“August 1, 1944,” he says, as certain as if it were yesterday. “The first day of the Warsaw Uprising.”

“How’d you know to start? And what to do?”

“Well,” he answers, “a knock came at the door one day and a messenger told us it would begin at seventeen hundred hours on August 1. Up until right before the Uprising, I had been helping train and keep track of the younger Eagles at the camp we were running about thirty to forty miles outside Warsaw.”

“What exactly were you doing at the camp?”

“Teaching boys survival and combat techniques.”

“How old were they, Dad?”

“Ten- to thirteen-year-olds,” he says. “We had to encourage them at a young age to believe that ‘Poland will be free.’ ”

I would later locate a book about the Young Eagles, which would provide both for my dad and me great historical information, as well as a few surprises. The “Eaglets,” formed in 1933, were based on a group called Lvov Eaglets, who fought against the Ukrainians right after World War I. Throughout history, Poles always had to fight to survive. Patriotism was in their blood. The new Eaglets organization was designed to instill patriotism in Poland’s young people, and more to the point, to prepare them to fight and die for their country.

It is mind-boggling that such young people were being made “combat ready,” but if you grew up in Poland, you always had to be ready for war. No wonder my father used to tell us, “You cannot let evil roam unchallenged and that freedom is always worth fighting for.”

Not a typical life lesson for a young girl in Greenwich, Connecticut.

“I was one of the older guys at the camp at that time,” my dad says. “So when Lieutenant Stan was called away to start organizing the fight in central Warsaw I was left in command of all the Young Eagles. He gave me a handful of zlotys, the Polish currency, and instructed me to watch over the kids until he returned. I was frustrated that I was being left behind while Lieutenant Stan, whom I considered a friend and mentor, was about to risk his life for our country.

I stayed with the camp for a bit, but then, in a crisis of conscience, I went to the old woman who was our cook to ask what I should do.”

“How old was she?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” he responds, obviously frustrated by my interruption of his storytelling. “She was a grandmother type.” He watches as I write “grandmother type” on my legal pad. My father, too, was always good at noticing detail. “I knew the Uprising could begin any day, and I wanted the perspective of someone who had lived a full life and had a family of her own. I needed her to tell me what the best course of action was.”

“‘What would you do,’ I asked her, ‘if you knew that something dramatic was about ready to happen in which you and your family could lose their lives? Would you want your children away at camp, or home with you?’ The woman quickly answered that she would want her children as close as possible. I thought hard about her answer while I stayed at the camp a little longer, but about a week later I decided that I had an obligation to return the Eagles to their families and to help Lieutenant Stan fight the fight. I used the money he left me to rent two horse carts, and I took all the boys back into Warsaw to reunite them with their parents. Not long after I got all the boys to their homes, I met back up with Lieutenant Stan and the rest of the adult members of my unit.”

“Do you remember the name of your unit, Dad?” I ask.

“Gozdawa Battalion. Named after a famous fighter in Uprising history. He basically came up with the idea to use young underground fighters in the fight for freedom.”

“Did your parents know you were doing this yet?”

“They knew I was in the Young Eagles, but I don’t think they had any idea I had joined the Resistance. Remember, I had done that three years earlier when I was sixteen, really fifteen. I didn’t want them to worry about me. I was always afraid the SS would capture my mother and torture her if the Germans found out her son was in the Resistance.”

“Did your parents ever ask you about it?”

“Not specifically,” he says. “But they may have suspected, because they did once find a bulletin I had containing all the news on current events and information on German troop movements. They questioned me about it, but I lied and said someone gave it to me.

“My unit was operating in relative secrecy, part of the Polish underground. The different units and cells of the Resistance were kept separate and secret, organizing themselves through messages sent by couriers between anonymous commanders. Our superiors in the underground would issue orders about points of interest and objectives, and the information was disseminated by the women and girls who served as messengers. We had to be ready for just about anything at a moment’s notice.”

“Did you have uniforms?” I ask.

“We started the Uprising just wearing the clothes on our backs, our civilian clothes, but shortly into the Uprising, we got into a German storage facility and took German uniforms. So, we wore German uniforms, except we added red and white Polish armbands. The armband had a big WP on it, for Wojsko Polskie, translated to mean ‘Polish army’ or ‘Polish military.’ It had an eagle between the letters, the symbol of Poland, representing strength and freedom. I think it is originally based on an old Polish legend.”

“What did the girls wear?” I ask.

“They wore their civvies and the armband. The armband was important. It was the only way Poles knew not to shoot at each other.

Whenever I was worried about being shot by a Pole, I’d wave my arms so they could see the armband. I had it all the way through. I even brought it to America, but I think your mother threw it away.” I knew she hadn’t.

“What about shoes?” I ask. “Did you wear boots?”

“That’s a good one,” he says. “Early in the Uprising, I was in the Old Town area, running over ruins and bricks, trying to stay ahead of the Germans, and the old shoes I was wearing were falling apart because the terrain was so tough and full of rubble. One buddy pointed to my shoes and said he knew of a nice shoe store nearby. He took me there, and it was of course abandoned, so I got myself a nice pair of brown suede shoes. Little did I know those shoes would stay with me all the way through the war.”

“And what about weapons?” I ask. “What weapons did you have?”

“Ah! Great question!” He laughs. I laugh, too. “I asked Lieutenant Stan the same question: ‘What about our weapons?’ And with a straight face he told me, ‘We don’t have any.’ He said the weapons were hidden in the woods, and since Warsaw was being squeezed in all directions, we couldn’t get access to them. In our whole unit, we only had two measly nine-millimeter handguns. I was stunned. We were supposed to be an elite unit!”

I am stunned, too. It seems like lemmings heading to a cliff, a suicide mission.

“But we had a tactical advantage over the Germans because we knew every street. Though we were woefully underequipped to clash with the Nazis, I was literally fighting to save my own backyard.

Most of our units only had a few guns, and ammunition was even scarcer. Because of how difficult it was for us to arm ourselves, fighters in the Resistance jumped at any chance we got to claim a cache of weapons.”

“What were the civilians doing during the Uprising?” I ask.

“It was hard to believe that civilians still called the place home, but they did. When the Uprising began, the city went from bad to worse. Already in ruins from the bombings at the beginning of the war, it became what seemed like an endless field of rubble. The streets we were fighting so desperately to claim were lined with what was left of homes, bombed-out, burned-out shells. Many were still occupied by families hiding in their basements.”

From "Quiet Hero" by Rita Cosby. Copyright © 2010. Reprinted by permission of Threshold Editions.