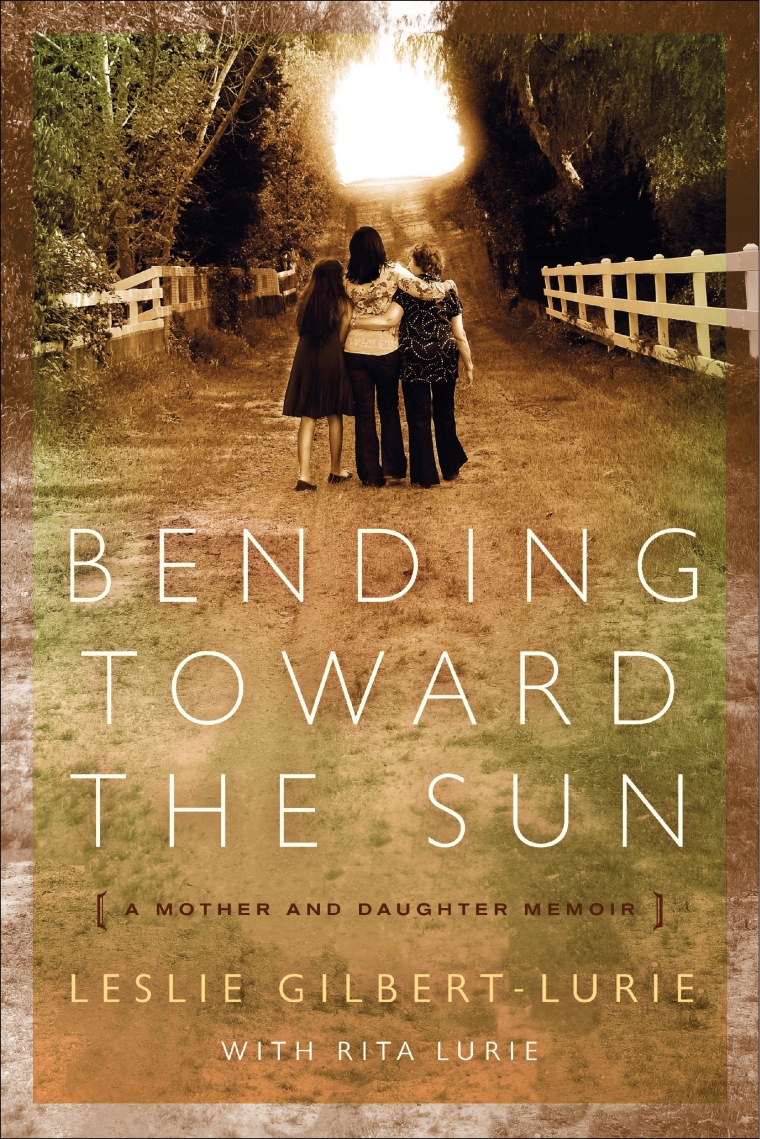

Holocaust survivor Rita Lurie and her daughter, Leslie Gilbert-Lurie, offer a firsthand account of survival and healing in the memoir “Bending Toward the Sun.” The book explores how the trauma of the Holocaust extends into the lives of second and third generations. Here is an excerpt from chapter one.

Chapter 1: Childhood, Interrupted

I was four years old, in 1941, when I saw my first airplane. On a peaceful, sunny day when the sky was clear blue with cotton-puff clouds, I was flying a kite in our wheat fields while my father gardened. Hearing a noise from up above getting louder, I cranked my neck to look up. I couldn’t take my eyes off the object floating by.

“What is that? What a strange-looking bird.”

“It’s a machine that can fly,” my father said.

“How does it stay up there?” I asked.

“I’m not sure. It’s called an airplane, and it carries people to faraway places.”

I was overwhelmed by feelings of joy and freedom. The world was so full of promise.

My home, in Poland’s southeast region, was part of a small village called Urzejowice (oo-je-VEET-sih). The house itself was painted a sunny yellow with white trim and surrounded by a white picket fence. Our front yard, brimming with plum trees, sunflowers, and sweet pea vines, seemed like a paradise to me. Poland’s winters were harsh, but once spring came, my sister and I loved playing outside in the garden, waiting for our father to return from work. We made houses and pies out of mud, improvised games like tag, and waved to neighbors passing by.

“How old is she again, Sara?” I whispered to my sister one day, as our elderly neighbor floated by on a gurney carried by two of her sons.

“She’s one hundred and two,” Sara said. My five-year-old sister was wholesome looking, with a heart-shaped face, dark, deep-set eyes, and straight brown hair.

“Wow! That’s so old.”

“Tatu says we should all live that long,” she said. Our father’s name

was Isaac, but we called him Tatu, which meant “daddy” in Polish.

“Tatu wants us to be old like that?” I asked.

“Ruchel, it’s an honor to grow that old.” Losing patience with me, Sara looked out into the distance. “There he is!” she shrieked.

“That’s not fair. You always get to see him first,” I said.

“I’m a year older. I can see farther than you.”

Now I, too, saw my father. He was walking proudly, with his shoulders back and his head held high. He and my grandfather and uncles were in business together, selling groceries, clothing, and cows. They bought cows from gentiles and sold them to Jewish slaughterhouses in the big cities, where they would be butchered for kosher meat. As usual, my father was impeccably dressed, in a dark suit and maroon tie that accentuated his straight white teeth and wavy black hair. He was carrying a package wrapped in brown paper. Often, he returned from business trips bearing wonderful surprises. Sara and I raced down the path, vying to be the first to fly into his arms.

“Hi, children,” my father said. As his eyes rested on us, they began to dance, and crinkled at the edges. He tucked the package inside his suit jacket and lifted us into the air one at a time. “What are you up to?”

“We’re waiting for you, Tatu,” I said.

“Where are your mother and brother?”

“They’re in the kitchen, and Mama is cooking soup,” Sara said. “Is that a present for us?” she added as we approached the front door, pointing to the bulge protruding from my father’s jacket.

“Let’s see when we get inside,” he replied. He always seemed to lead the way. He was the peacock in our home, and the ultimate authority.

In the kitchen, my father greeted my mother, Leah, with a kiss and hug. Then he took my two-year-old brother, Nachum, and hoisted him into the air. Nachum squealed with delight. He had pale, Dresden-like skin, pitch-black eyes, and brownish gold hair.

“Now can we open the surprise, Tatu?” I said.

He handed me the package. My sister and I tore it open, revealing yellow silk embroidered fabric that looked like rays of sunshine dancing in our arms. I held it up for my mother to see.

“It’s exquisite,” she said.

“Can we sew dresses from this?” Sara asked. “Or is it too fancy to cut up?”

“We can make special dresses for Shabbos,” my mother said. She was sensitive and kind, and she adored my father. He loved her, too. Isaac Gamss and Leah Weltz had grown up in the same village, and their marriage, in 1935, had been arranged by a matchmaker. He was thirty-two, and she a few years younger.

My mother was attractive and unusual looking, with dark, deep-set eyes, full eyebrows, a patrician nose, long, curly dark brown hair, and beautiful skin. At five foot seven, she was tall for her day. Still, my father was always the bigger, more outgoing personality. The distinguished suit he was wearing that afternoon, alongside my mother’s plain cotton housedress and apron, seemed to accentuate the contrast.

Sometimes my mother would cry for no apparent reason. Her own mother had died when she was a young girl. I often wondered whether she was still grieving over that long-ago separation. Or perhaps she was just tired from working so hard. In addition to cooking and caring for three young children, cleaning our home, and washing our clothes in the nearby river, she also helped my father pick fruits and vegetables and tend to our livestock in fields that we leased from a man named Kapetsky, the aristocrat in town. I liked to help milk the cows, although someone first had to lift me onto the milking stool. The only time I saw my mother sitting down during the day was when she shelled peas or snapped green beans.

Back in the kitchen that afternoon, my father had one more surprise. From inside his suit jacket he pulled out another package. With a twinkle in his eye he said, “Hopefully, these will look nice with the dresses.”

My sister and I were so excited. We ripped open the brown wrapping, pulling out two pairs of cream-colored patent leather shoes. Sara grinned from ear to ear. When she smiled, her face lit up. Then she handed me the smaller pair.

“They’re so beautiful.” I sat on the floor to push my bare feet into them.

“Nachum, what are you doing?” I heard my mother ask. I looked over

to see my brother pulling apart the brown wrapping paper and scattering

pieces all around.

“Playing,” my brother said.

Sara and I burst out laughing. My father did, too.

A few days later, the yellow fabric had been transformed into two holiday dresses, by whom I’m not certain. Maybe my maternal step-grandmother, Simma, who lived next door with Grandpa Nuchem, had sewn them. I used to watch her knit while I threw balls of yarn to her cat. Sometimes she also made me rag dolls out of muslin, with painted faces.

Our home formed the backbone of our spiritual, cozy world. Affixed to the right front doorjamb was a mezuzah — a small, oblong container with verses from the Torah inside — which we kissed whenever we passed through. Also, before bedtime, we said a special prayer and planted a kiss on the mezuzah in the master bedroom. I fell asleep secure in the knowledge that God was watching over us.

In our village, although the Jews worked very hard, they were generally looked down upon by the Christian Poles. On Shabbos, however, the Jews elevated themselves. Shabbos was the highlight of the week for our family. From Friday afternoon to Saturday night, normal life was put on hold. My mother spent Thursdays and Fridays cleaning and cooking in preparation. Dreamy scents of chickens stewing, soup boiling, and cakes baking filled me with a sense of peace and well-being.

The most heavenly aroma was that of challah baking in the oven. My sister and I would stand by our mother’s side, enrapt, as she kneaded the dough, formed it into loaves, and slid the loaves into the oven. When they were ready, my mother would announce, “Girls, come and have a nibble.” Sara and I would scurry back across the kitchen, past the red enamel pots used for milk products to one side and the blue pots, for cooking meat, to the other. My mother would tear off a piece of soft, piping-hot bread from the tiny extra loaf she baked just for us. I would close my eyes and pop a morsel into my mouth. It practically melted on my tongue. I can’t manage to remember ever being kissed or hugged by my mother, although I’m sure that I was, but I do remember feeling her warmth and love whenever her challah was baking.

By sundown each Friday, our home looked beautiful. The wooden table in the kitchen was covered with a white cloth and set with sparkling china and colorful crystal. One Friday, just before Shabbos began, Sara and I were twirling around in our beautiful, newly created yellow dresses when there was a knock at the door. Before my mother answered it, she leaned down and said, “Ruchaleh, bring the package.”

I reached up to the kitchen counter, grasped a container of food, and brought it to her. She was standing in the doorway, dressed elegantly in a bright silk blouse, a black skirt, and a pearl necklace, as she greeted a Jewish man in ragged clothing.

“Good Shabbos,” my mother said.

“Good Shabbos. Do you have any food to spare, or a few zlotys?”

“We have food,” I interjected, pointing to the package in my mother’s

hands.

“God bless you,” he said.

When the man left, my mother looked at me. “Where’s your smile, Ruchaleh? You should feel good. Did you know that charity elevates you in heaven?”

“Mushe, that man makes me sad. Why doesn’t he have his own food?”

“He is an orphan. Square meals do not come so easily for some people.”

My mother led me back to the kitchen table, where my father and sister were waiting. Nachum, my young brother, was already asleep in my parents’ room. Shabbos could not begin until sundown, which meant that in the spring and summer months it began quite late. My mother lit candles, one for each member of our family, and said a prayer. Then she sat beside my father on the wooden bench, across from Sara and me. We were expected to listen politely to the adult conversation, and only to speak when granted permission. Over dessert, however, we joined in to sing traditional songs and chant melodies thanking God for our blessings. Everything felt serene and holy.

Our home was newly built, and another bedroom was still being added on for Sara and me. Until that was completed, we shared our parents’ bedroom, except on very cold nights, when we slept near the stove in the kitchen. My parents’ bedroom was decorated with a huge, gleaming wood armoire, a crib for Nachum, and gorgeous lace curtains hanging from copper rods. A set of exquisite blue ceramic birds sat near a crystal clock upon one of the nightstands. On Saturday mornings I would open my eyes at the first sign of light streaming through the windowpanes and jump right into my parents’ bed, giggling. Lounging like this was reserved for holidays, and the Sabbath.

My paternal grandparents, Aharon and Paya Neshe, lived a few miles away in the town of Przeworsk (shev-orsk), along with nine of their twelve children. They seemed like a wonderful couple with a lot of love. My father was their firstborn. Since Grandpa Aharon had a Torah, we walked to his home on Shabbos mornings so that my father could pray there with the other males in the family.

“What was that?” my sister asked, whenever she heard any noise along the way.

“It’s not a dog. Don’t worry,” I remember saying. Ever since a dog chased us one morning, Sara had been wary of unexpected noises.

My grandparents’ white clapboard home sat atop a grassy hill, surrounded by wildflowers. As we climbed up the knoll and past the brick well out in front, we anticipated the warm greeting we would receive from our grandmother, Paya Neshe. She was revered in our family, and always seemed to be doing good deeds for needy people.

“Good Shabbos, lalkales [dollies],” she would say when she opened the door to greet us. She was plump, and wore dark, loose-fitting dresses accessorized with jewelry. Her wig, which traditional Jewish women of her generation wore, was dark and curly.

“Good Shabbos, Bubbe,” we would respond, using the Yiddish term for “Grandma,” pronounced bub-bee. “Come. Come into the kitchen,” she always urged. “I baked treats for you.”

On the way we would walk through a large, beautiful room with shiny, golden wood floors and a harp off to one corner. There, my father joined Grandpa Aharon and my eight uncles in a semicircle. When they were praying, I wasn’t allowed to say a word. Grandpa Aharon, in his early sixties, was always easy to spot. He sported a black suit and white shirt like his sons, but he also wore a big velvet hat, a mustache, a beard, and payis (side locks). My father and his brothers, eager to fit into the gentile world, dressed less traditionally.

On Saturday afternoons, our extended family often took a stroll in the town square, passing by the small grocery store, the pharmacy, the Catholic church, and a tiny candy store owned by one of my father’s sisters, Chaya Shaindl, and her husband. One Saturday, I held my aunt’s hand as we walked past her shop.

“Can we go inside for just a few minutes?” I asked.

“Not on Shabbos,” she said, and smiled. “But I have an idea. Why don’t you tell me what your favorite candy is, and I’ll bring you a piece during the week.”

“I like picking them myself,” I protested. I loved going into her shop, reaching a serving spoon into the glass bowls, and pulling out turquoise rock candy and the colorful bonbons covered in beautiful, bright wrapping.

In the summer, we played outside until supper was ready. Then our mother would call us in. “Kim en dem hois, Sara and Ruchel.”

When we were called to dinner, it meant now. There were a lot of do’s and don’ts in our household, and my parents were not afraid to reprimand me when they needed to. Once, I remember, when our kitchen was painted, one of the wet white walls looked so delicious that I walked up and licked it. Immediately, my tongue was afire. “Ow!” I screamed.

“That paint can make you very sick. Don’t ever do that again!” my father yelled. He could be short-tempered at times.

“I won’t. I promise,” I vowed, running from the room in tears.

I felt very secure with these rules. Over warm candlelit suppers, my parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles had lively conversations about business and family. I listened, taking everything in. Afterward, we gathered around the fireside (priperchik in Yiddish), listening to stories and sipping tea, with sugar cubes in our mouths. The adults often spiced their tea with homemade liqueur. “It helps warm our kishkes [stomachs],” my father would say. On some evenings my parents made up their own stories, and other nights they read to us from books. Even though we lived in a small village, my parents wanted us to be well educated.

“This is one of my favorites,” my father would often say, before he began a story.

“Please don’t tell one with dybbuks tonight,” I always pleaded.

Often, my parents’ fables included dybbuks, or evil creatures that took possession of humans if they didn’t live according to the Torah, or the highest values. When I misbehaved in some minor way, I was afraid to fall asleep at night for fear the dybbuks would appear.

“Ruchaleh, they won’t bother you as long as you’re a good girl,” my parents would assure me

In reality, the dybbuks had already appeared. My orderly, loving childhood, where everything had its time and place, was far more precarious than I had been aware. By 1937, the year I was born, anti-Jewish incidents had been taking place throughout eastern Europe. In August of that year, 350 assaults against Jews were recorded in Poland alone. Hitler’s Nazi propaganda, casting Jews as the source of all evil, had stirred up jealousies and hatred. Ten percent of the Jewish population in Poland, over 395,000 Jews, had been driven to emigrate by that time. But as a very young child living in a remote village, I was oblivious to any of this tension. I was not even aware that in September 1939, when I was two, Germany had attacked and easily defeated Poland. The German army had torn through town after town, killing every Pole in sight.

Thus it came as a terrible shock to me, that day in 1942, when a sea of gray German tanks invaded our small town, with swastikas or Hakenkreuze molded onto them and their cannons protruding with quiet menace. I could see them out of our large kitchen window, which was lightly coated with frost, as they rumbled by. I can still feel that chill today. Fear rolled through my being like a dark fog.

Although some German soldiers had been in our village for three years already, since the start of the war, until now they had been persuaded by the town’s wealthy landowner, Mr. Kapetsky, to leave the Jews alone. But recently Kapetsky had fled, German troops had grown in number, and the situation was growing progressively more dangerous. For days on end the adults fretted over what to do. My parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles paced around the kitchen, frantically debating their options.

“The rumors keep getting worse. Every day they’re rounding up Jews and deporting them to God knows where,” I overheard my father say one day. I stood off to the side, feeling very alone.

“Iche, it’s worse than roundups, there’s bloodshed everywhere. In Warsaw, they’re in ghettos, starving to death. Next thing they’ll burn down our homes,” Uncle Max said. He was thirty years old and had dark hair and beautiful deep-set eyes, like all the Gamss siblings. I had always thought of him as the funniest of my uncles, and it scared me to see him so serious.

“The Germans don’t care about our small village. They’re not going to burn down our homes,” Grandpa Aharon said.

“They might,” Uncle Libish said. He was married to Tsivia, my father’s middle sister, and as he spoke, my father furrowed his brow. There seemed to be some sort of tension between the two men, perhaps because Uncle Libish was also in the business of selling cows, which put him in competition with my father. “Mr. Arnold says this is a war unlike any others.”

“Mr. Arnold?” Grandpa Aharon asked.

“Yes, Papa. He’s the nicest of our soldiers,” Aunt Tsivia said. She was short and curvaceous, with curly brown hair and wise dark eyes. She had won a local beauty contest as a teenager, and at thirty-five was still attractive. She was also feisty, and she looked her father confidently in the eye as she referred to Mr. Arnold, one of the three German soldiers who had been living in their home since 1939.

“We play chess after work, and he tells me things,” Libish said.

“Now I’ve heard everything. My sister’s husband plays chess with a

Nazi,” my father said. As the eldest son, he knew he held a place of honor in the family, and that his siblings would support him in almost any dispute.

As each day passed, the world became a scarier place. There was less food, since we could no longer safely go outside to gather produce and care for our livestock. We sensed that anything could be taken away from us at any time. Then a series of incidents hit even closer to home. One evening, my family was sipping tea in the kitchen when the front door burst open. Three German soldiers in muddy boots stomped in.

“Where is Isaac Gamss?” the shortest one said.

“What do you want?” my father asked. None of them answered. Instead, they turned over chairs and threw things around. My sister and I covered our ears and clung to our mother.

“Why don’t you just tell me what you’re looking for,” my father said.

“We’re in charge of your village now,” one of them finally said as they abruptly turned around to leave.

My father came home another day looking confused and disheveled. My mother took one look at him and started crying. She lifted up his shirt and saw bloody welts on his back. Then she led him into the bedroom. Later, we overheard that he had been detained for questioning and beaten by a German soldier. A few days after that, Uncle Max raced into our home. He didn’t seem to notice my siblings and me, playing in the kitchen.

“Iche, come quick,” Max called to his eldest brother. My parents rushed into the kitchen, serious and pale, as though they had seen one of the dybbuks from their stories.

“What is it, Max?” my father asked.

“It’s an order. From the Gestapo. We have to report to the train station,

and Papa wants to see all of us right away!”

“We just received our own edict,” my father said.

The family gathered in a circle in my grandfather’s kitchen. I sat off to the side with my sister, brother, and three cousins—eight-year-old Sally, six-year-old Miriam, and Lola, who was five like me. The adults whispered, trying not to scare us children. But their efforts were in vain. The same room that had once been the hub of lively conversation and sweet aromas now felt cold and frightening. The biggest change of all was that Grandma Paya Neshe, always the heart of the kitchen, had recently passed away. She had been ill, I believe as a complication of her diabetes, but had to be brought home prematurely from the hospital when the doctors fled to escape the Nazis.

“We cannot go to the train station,” Grandpa Aharon stated right

away. My father nodded his head in agreement. “So I have an escape plan.” The room was very quiet as my grandfather described his plan. The family would leave home in the dark of the night and slip into hiding. I didn’t know what this meant, but it sounded scary. Then, he explained, we would search for safer hiding places. Everyone just listened until he got to a tricky part. “We’ll need to split into groups,” he said calmly.

The adults looked at one another with puzzlement, but twenty-two-year-old Uncle Benny was the only one to speak up. He had a dry sense of humor and could be stubborn at times. Uncle Benny thought we should all stick together. He mentioned something about there being strength in numbers. But my grandfather stood his ground.

“No. My plan comes from the biblical story of Jacob,” Grandpa Aharon said. “Remember when Jacob returned home with his family after twenty years in exile?”

The adults nodded their heads. I nodded, too, but had never heard the story. Later, I learned that Jacob, fearing his brother’s revenge, split the family into two camps so that at least one group would remain safe.

“This way, if any of us are caught, God forbid, at least others will survive.” Grandpa Aharon’s words hung in the air like December clouds portending cold, stormy days ahead.

My father looked over at his children. When his eyes met mine, he couldn’t even force a smile. Grandpa Aharon, meanwhile, was sorting the family into groups. Five of his younger children would stay with him. Three other sons, my uncles Max, Benny, and Henry, would make up a second group. “You’re strong enough to go off on your own,” Aharon told them. Then he added his youngest son, sixteen-year-old Norman, to that group, believing he would be safer there. I felt sorry for my favorite uncle, with dark hair and beautiful, soulful eyes. He clearly preferred to remain with his father.

Finally, Grandpa Aharon turned to my father and Aunt Tsivia, his two children with children of their own. “Your families will travel as one group so that the children don’t endanger the others if they make too much noise.” I assumed he meant me because I talked loudly sometimes. But I could keep quiet, too. I wanted to tell him this, but he had moved on. He was saying that we should head toward the farm of a man named Stashik Grajolski, who might take pity on the children. Grandpa Aharon and Grandma Paya Neshe had looked out for Stashik and his sister after their parents died near the end of World War I. My grandparents had made sure that the teenage orphans had food and clothes, and that they attended school and church.

“Stashik and I were friends in the army,” Uncle Max added. “He’s a good, smart family man.”

Sara and I held hands, frozen. My cousins Sally, Miriam, and Lola looked just as frightened. Three-year-old Nachum kept moving onto and off our laps, trying to get our attention. But for once, we all wanted to listen to the adults.

“How will we sustain the children hiding out in the forest?” my worried mother asked. “Our babies are going to sleep outside like the dogs? Maybe we should just go to the train station. How bad a place could they take us to?”

Aunt Tsivia was concerned, too. “Feigie is only a year old,” she said, glancing down at the baby in her arms. “She won’t survive the cold nights outside, and I can’t bear to lose another child.” Feigla’s twin sister had died as an infant.

Uncle Libish put his arm around his wife, now in tears, but spoke directly to his father-in-law, Grandpa Aharon. “I’ve evaluated the edict through Mr. Arnold’s eyes. He made it clear we should not go to the train station.”

This time my father agreed with Uncle Libish. Apparently everyone did. Only Uncle Henry had refrained from voicing an opinion. He was twenty and the quietest of the siblings. He had remained silent all evening, as the others spoke on top of one another.

“We must leave tonight,” Grandpa Aharon finally ruled in a voice filled with resignation, yet loud enough to be heard over the chatter.

Back home, my mother prepared packages of hard-boiled eggs, vegetables, and bread for us to take along. My father came into the kitchen and lifted me up. I wrapped my brown lace-up shoes around his waist and my arms around his neck. “Let’s say good-bye,” he said. He proceeded to carry me to the doorpost of the master bedroom and then to the front door. We kissed both mezuzahs as my father prayed to God for us to survive. I tried to pray with him, but I was too scared to remember the words. Instead, I hugged him so tightly that I could feel his heart beating through my chest.

We quietly left home, our family and Aunt Tsivia’s, dressed in layers, with packs on our shoulders. Walking down our street in complete blackness, I squeezed my mother’s hand tightly.

Reprinted with permission from “Bending Toward the Sun” (HarperCollins) by Leslie Gilbert Lurie, with Rita Lurie.