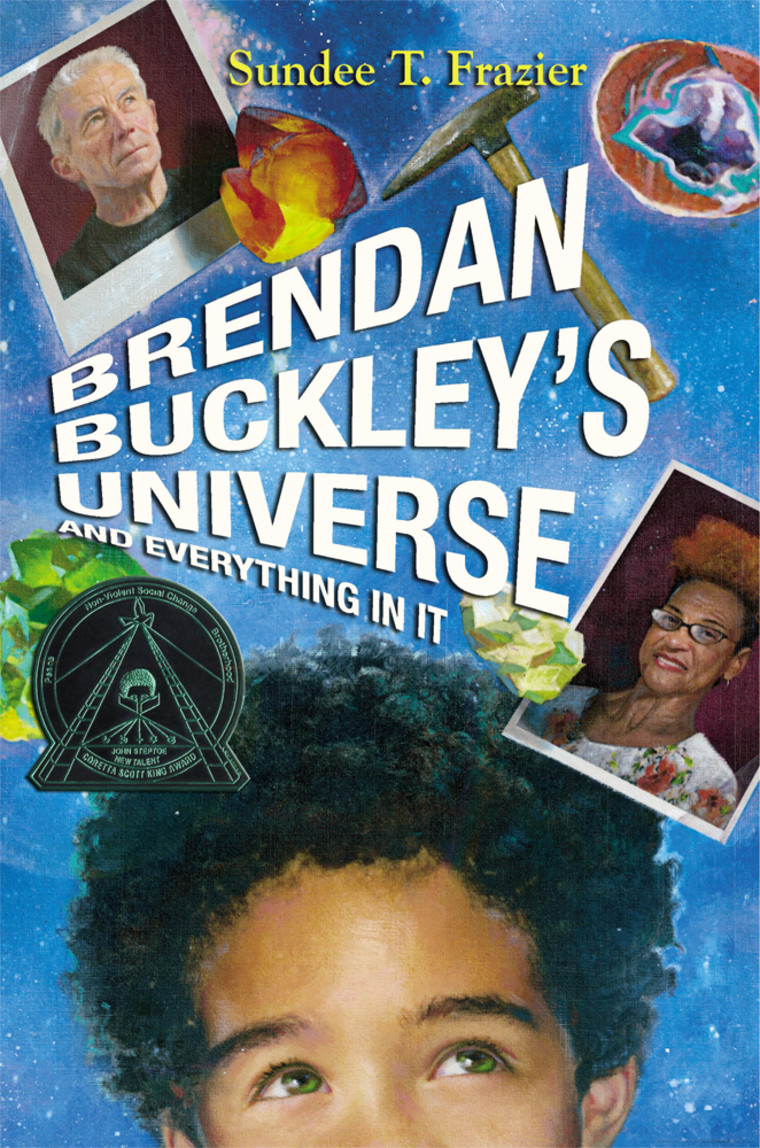

Ten-year-old Brendan Buckley is passionate about science and he documents all of his questions about various subjects — ranging from dust to centipedes to black holes and more — in a confidential notebook. Summer break arrives, and Brendan is faced with questions of a different kind when he discovers that his estranged Grandpa DeBose, who is white — not black like Brendan, his dad or the late Grandpa Clem — lives nearby. Brendan forms a secret friendship with him and sets out to find the reason behind his absence, but what he discovers can’t be explained by science. An excerpt.

Chapter One

I ran my hand across my notebook’s title. Summer vacation had finally arrived. That meant seventy-nine days to find answers to the questions I’d already recorded. Seventy-nine days of scientific experimentation. And seventy-nine days to mess around with Khalfani, swim in his pool, and get to the next level in Tae Kwon Do. Khal and I are only five ranks away from our black belts.

The thing I wouldn't be doing was fishing every Monday with Grampa Clem. When Grampa Clem died in April, it was sort of like having my leg taken away. You always expect it to be there, but then to one day wake up and find it gone? Suddenly everything's different and there's nothing you can do about it.

Now Gladys is my only grandparent, because my other grandma died right after I was born and I've never met my other grandpa. Mom doesn’t talk to him. Or about him, either, which makes me wonder what happened. But I guess I can't miss someone I've never even known.

The one time I asked where he was, she bit on her lip, and her forehead bunched up like when she cut her thumb and had to get stitches. She just said, “Gone,” and we’d talk about it when I was older. So that's the One Thing I know not to ask questions about.

I turned to the front section of my notebook, which I’d titled The Questions. The back section was called What I Found Out. Under, “Do centipedes really have 100 legs?”, “What’s inside a black hole?” and “Do boys fart more than girls?” I wrote my latest questions about dust.

Mr. Hammond told us that scientists’ questions compel them to find answers, and that’s how they make their discoveries. I asked Mr. Hammond what compelled meant, and when he said it meant to have an uncontrollable urge that won't be satisfied until you find what you’re looking for, I knew exactly what he was talking about. I get compelled all the time.

I ran to the bathroom with an eyedropper from my microscope kit and suctioned some water from the faucet. I went back to my room, squeezed a couple drops onto the slide and pressed another slide on top. I stuck the dust under the lens.

The cool thing about my scope is that it displays whatever it's looking at on my computer. I clicked a couple times to open the program and up popped my dust — magnified 400 times.

It was basically a bunch of small flakes. But flakes of what? I opened an Internet article called “Dust Creatures” and started reading.

The article said when you examine household dust under a microscope you can usually spot ant heads or other insect body parts. I had just clicked over to my microscope display to look for bug legs when a car door slammed outside.

I glanced out the window. Dad was back with my grandma, Gladys. A minute later the front door opened.

“I’m here!” Gladys shouted.

I got up to say hi because I wasn’t seeing any bug parts, and because any minute Gladys would show up in my room anyhow. Gladys doesn't pay attention to my “Experiment in Progress” sign.

I stood at the top of the stairs that go down to the front door. Gladys was bent over, pulling off her shoes.

“These bad boys got to go!”

Dad tried to squeeze in behind her.

Gladys looked at him over her shoulder with her eyebrows raised. “Where's the fire?”

Mom says that Gladys can be testy, like a bull that's been prodded one too many times. Gladys's nostrils were flared. I could almost see the long horns coming out the sides of her head. Dad was about to get it.

“Hi, Gladys,” I said. She stood up straight and Dad slipped through. He tipped his head at me. That was his way of saying, “Thanks, son.” Even if all my questioning and experimenting sometimes gets on Dad’s nerves, we’re still partners.

“There's my granbaby.” Gladys started up the stairs. “Come give me some sugar.”

Gladys pushed herself along by the handrail, as if she were a hundred years old or weighed five hundred pounds. She’s old, but she’s not crippled or hunchbacked or anything. And she’s not fat. Gladys reminds me of a chicken with a rooster head. She’s got skinny legs and bony elbows that stick out like wings. Her hair is short and black, but on top it’s orange and piled up high like curly popcorn. It comes forward, sort of, like it’s going to tip over. The top is the part that makes me think of a rooster. And she wears pointy glasses.

I stepped down a few stairs and kissed her cheek. Gladys’s cheek feels like a football. I know because I tried kissing a football once to see if it felt like Gladys’s face. Gladys’s skin is about the same color as a football, too. I wrote these things in one of my observation notebooks, and I for sure marked that one CONFIDENTIAL.

Reprinted with permission from Delacorte Press/Random House. This is Sundee Frazier's first children's book. She is also the author of “Check All That Apply: Finding Wholeness as a Multiracial Person” and you can visit her at www.sundeefrazier.com.