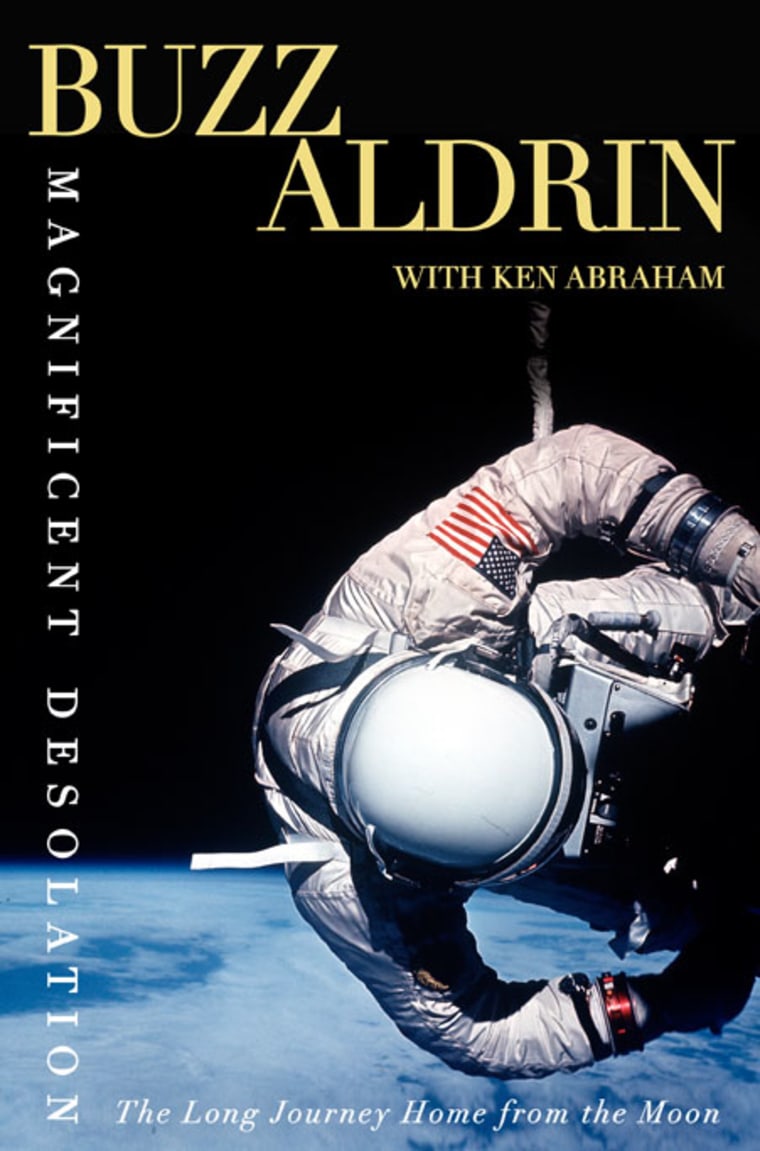

When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took those famous steps that were watched by hundreds of millions, they instantly became two of the most famous people on the planet. In “Magnificent Desolation: The Long Journey Home From the Moon,” Aldrin recounts that experience — from takeoff to splashdown — in breathtaking detail, and his harrowing return to normal life after the mission, when the astronaut battled depression and alcoholism.

In early 1974, a Hollywood television and movie producer, Rupert Hitzig, came to our home in Hidden Hills to offer a formal proposal for the television movie based on “Return to Earth.” Rupert had written the Broadway musical hit “Pippin,” had produced an installment of ABC’s “Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell,” and was in partnership with the well-known comedian Alan King. A friendly fellow, Rupert was fascinated by our home’s “moon” décor, including a life-sized photo of the “visor shot,” as the famous picture of me on the moon was now known. Much to my delight, Rupert was especially intrigued by our “Moon Room,” which featured a well-stocked bar. I had found a new drinking buddy.

“Come on, let’s get a drink,” I said, motioning for Rupert to sit down at the bar. It was only twelve-thirty in the afternoon. We talked and drank, talked and drank. Rupert loved drinking as much as I did, and we downed one gin and tonic after another. Rupert and I talked much about our fathers — his was a doctor in New York, who sounded almost as opinionated and overbearing as my father. We both chuckled over my dad’s outrage when the U.S. Post Office issued the stamp with Neil Armstrong’s image and the caption “First Man on the Moon,” though of course I had been taken aback as well. Rupert laughed uproariously when I told him that besides lobbying the post office incessantly, my father went so far as to picket in front of the White House, with a huge placard bearing the message, “My Son Was First, Too.” By the time Rupert and I actually got around to signing the contracts, we were sloshed.

We arranged a follow-up meeting a few weeks later, at the Beverly Hills Polo Lounge at five o’clock. I arrived at the Lounge before 1:00 p.m. By the time Rupert showed up shortly before five, along with his friend John Roach, I was thoroughly intoxicated. Rupert tried to talk business with me, but my interest wavered, as did my conversation. At one point Rupert leaned toward me and spoke quietly but firmly, “Buzz, don’t you understand what a hero you are? Don’t you realize that every person in this room knows who you are and what you did on July 20, 1969?”

“Nobody remembers where they were on July 20, 1969,” I groused.

“I’ll prove it to you,” Rupert said. A young man who looked as though he could have been in a heavy-metal rock band was passing by our table, and Rupert reached out and grabbed his arm. “Excuse me,” Rupert said. “Where were you on July 20, 1969?”

Despite my attitude, Rupert was determined to see “Return to Earth” made as a movie, and we agreed to press on to build the production team and sell the project to a television network as a made-for-TV-feature-length movie. At least I think that’s what we agreed to, because that’s what Rupert did. He said that he had high hopes of getting a first-rate actor, Cliff Robertson, involved in the project, as well as an attractive female to play Marianne. Rupert had my attention.

“What do I need to do?” I asked.

“Nothing right now. I’ll be back in touch as soon as we have all the pieces of the puzzle put together.” Rupert went his way while I had one more drink for the road, or maybe it was two or three.

Gravitating to alcohol

I communicated with few friends during this time, at least not on any meaningful basis or about anything other than potential space projects. I can’t recall ever sharing my pain with another male friend or confiding in anyone that I was struggling to hold life together. Nor was I in touch with any of my fellow astronauts during this period; we had all gravitated away to new phases of our lives. There was little esprit de corps among the third group of astronauts, and certainly very little other than superficial interaction away from the workplace. While some of them, I later learned, had heard that I was having problems, I never heard from any of them, and frankly didn’t expect anything to the contrary.

More and more, I turned to alcohol to ease my mind and see me through the rough times. Because I could handle my drinking — or so I thought — and could consume a lot of alcohol without becoming uncontrollably inebriated, I refused to see it as a problem. I had been relatively open about my battle with depression, but I was not so forthcoming about my drinking problems. As far as I could see, there was nothing wrong. It was a time when almost everyone I knew was drinking heavily, so why not me?

When I was not drinking, my thoughts tended to lead me to a deeper sense of self-evaluation and introspection. What am I doing? What is my role in life now? I realized that I was experiencing the “melancholy of things done.” I had done all that I had ever set out to do.

Worse still, when I left NASA and the Air Force, I had no more structure in my life. For the first time in more than forty years I had no one to tell me what to do, no one sending me on a mission, giving me challenging work assignments to be completed. Ironically, rather than feeling an exuberant sense of freedom, an elation that I was now free to explore on my own, I felt isolated, alone, and uncertain. Indeed, as a fighter pilot in Korea, making life-or-death decisions in a fraction of a second, and then as an astronaut who had to evaluate data instantly, I consistently made good decisions. Now, as I contemplated asking Joan for a divorce, I found that I could not make even the simplest decisions. I moved from drinking to depression to heavier drinking to deeper depression. I recognized the pattern, but I continually sabotaged my own efforts to do anything about it.

By Christmas 1974, I had mustered enough will to divorce Joan. We had planned to take our three children to Acapulco for the holiday season, and this was where I would lay out my intentions to her. I actually thought that divorce might be a relief to Joan. After all, she had witnessed so much of my withdrawal into myself since returning from the moon, she even said at times that she didn’t feel I was the same person she had married. She told me that she would never walk away quietly and grant me the divorce, that she would fight for all she could get financially in divorce proceedings. I think she felt that if she could slow me down with financial concerns, she might be able to delay the divorce long enough to save our marriage. But I didn’t care about money; I never really did, and still don’t today. To me, money is a commodity that a person must have to function, not a goal in itself.

While Joan and I bounced from vitriolic conversations to silent, sullen, peaceful coexistence in the beachside hotel room, my sister Fay Ann called to say that while visiting with her family for Christmas in San Francisco, Dad had suffered a heart attack. He was in the hospital. “It doesn’t look good, Buzz,” she said. I racked my brain trying to decide what to do. Should I head for California, or remain in Mexico? I was already up to my neck in stress from trying to deal with my relationship with Joan, and I figured that Dad was either going to recover or he was going to die before I could get there. Fay Ann was staying with him in the hospital, so I remained in Acapulco with Joan and the kids. The extra days did nothing to improve our relationship, and on December 28, before I left Acapulco, Dad died from complications stemming from the heart attack; he was seventy-eight years of age.

Because of his military service, Dad was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Joan and our children did not attend the funeral, partially because of the costs involved in travel from California to Washington, D.C., but more because I chose to go alone. I stood stoically —as expected — while the uniformed soldiers carried my father’s casket across the frozen grass. My face remained equally as frozen as the casket was placed in position, the flag presented to my oldest sister, and the lonely sound of a trumpet playing “Taps” echoed across the rows of white tombstones. I didn’t flinch or shed a tear during the ceremony, but later that night I drowned my sorrows with alcohol.

A public issue

After the funeral, I returned to L.A., and initiated the divorce from Joan. We parted with no additional malice or rancor; we were both too mentally exhausted to fight over anything. Our marriage ended not so much with a loud blow-out as with a slow dwindling away of the energy required to maintain it. I moved into the Oakwood Apartments in Woodland Hills, a nearby section of Los Angeles, so I could stay in contact with our kids, and Joan and I remained friends over the years.

Meanwhile, my drinking was becoming more of a public issue. At one point, Perry Winston, a friend and fellow pilot, wrote a letter to me, frankly chiding me that as a national hero I needed to be more responsible about my drinking. Ironically, Perry worked for a liquor company, and the numbers on his plane were 100 PW, which could have been 100 Perry Winston, or 100 Proof Whiskey. Perry’s letter irritated me. Why is this guy on my case, I pouted. Doesn’t he recognize that I know what I’m doing? But then even a worse thought occurred to me: Maybe he is right.

Perry was one of the few people not in a recovery group ever to confront me about my drinking. Unfortunately, while landing his plane at Orange County, he hit some lights during his final approach and crashed. Perry did not survive, and I lost a true friend.

Withdrawing like a hermit

During the divorce process, I lived alone and tended to get extremely down on myself. My friend Jack Daniel’s, however, never failed to lift my spirits, albeit falsely. During this time, on my “up” days I was active, traveling, and working; I shared some of my latest homemade energy conservation inventions (along with a mock-up of Apollo) at the Inventors Expo II at the Los Angeles Convention Center, appeared at mental health and charity events, and even granted a few interviews. And I had the beginnings of an idea for a science-fiction story about space travel between star systems that I was calling “Encounter with Tiber.” In what became almost a regular pattern, though, when I felt the paralyzing gloom coming on, I’d begin to drink heavily. At first the alcohol soothed the depression, making it at least somewhat bearable. But the situation progressed into depressive-alcoholic binges in which I would withdraw like a hermit into my apartment.

When I ventured out into the real world, I traipsed from doctor to doctor, trying to find help, thinking that I was fighting depression and not accepting the fact that alcoholism could be just as much of an illness for which I needed help. The best thing one psychologist had to offer me was information about where I could go to purchase a good-looking hairpiece. He suggested that I seek out the services of the same guy who had prepared a hairpiece for one of the stars on the television show “Bonanza.” I thought, “Why am I listening to this sick guy?” I left his office, went around the corner, and at the first liquor store I found, I bought a bottle of Scotch. I couldn’t even wait until I got home. I swilled several swigs before pulling out of the parking lot.

I returned to UCLA to see Dr. Flinn, whom I had been seeing off and on over the last couple of years. Dr. Flinn referred me to the Veterans Administration hospital, where I could be admitted for a few days to dry out. While I was hospitalized there, Dr. Flinn came to visit me and suggested that I attend some of their Alcoholics Anonymous recovery meetings, held downstairs for the patients at the hospital.

I went to a meeting — in body, but not in spirit. As I looked around the room, I couldn’t see myself with this group. There were master sergeants and airmen and others, but nobody with whom I could identify, or so I thought. I was convinced I had no future with these people. I felt that I was too smart for this program; surely their simplistic answers and open admission of alcoholism could not help someone like me.

Some people get mean, violent, loud, or rude when they drink. I did not respond to alcohol in that manner. I wasn’t pugnacious, but I was less inhibited and felt more upbeat when I drank. I was charming in a sloppy sort of way; in my estimation, I was enlightened. To other people, I was smashed. But rather than admit I was running out of options as my drinking habits intensified, I chose to find new friends in different bars. That’s where I met Beverly Van Ziles.

Beverly was an interior decorator, with the kind of personality who enjoyed taking care of others; she was willing to manage the details of my life, so I was glad to let her. I moved from Oakwood Apartments in the Valley, to Federal Avenue in L.A., to be closer to Beverly’s apartment on Barry Avenue, one street over.

By 1975 I was drinking more heavily and more frequently. I’d stop drinking for a few days, and sometimes went as long as two weeks without a drink, but then I’d become frustrated over my inability to persuade anyone to use my scientific knowledge or ideas, and the gloom set in like an incessant London fog. The worse I felt, the more I tried to relieve my frustration through a bottle of Scotch, withdrawing into myself. I shut myself off from friends and family members, unplugging the telephone and often staying in my apartment for days at a time, the shades drawn, the doors and windows secured. Slumped in a chair, or in bed, a bottle in my hand, I stared aimlessly at the news channels on television.

When my food ran out and I got hungry enough, I would throw on some clothes, get in the car, and drive down to the nearest Kentucky Fried Chicken to bring home several buckets of barbecued chicken, but not before stopping at the corner liquor store to restock my supply of the hard stuff. When I got back to my apartment, I retreated to my bedroom, feeling satisfied that I could hide away for another couple of weeks.

Beverly pleaded with me to stop drinking, to pour the booze down the drain, and to straighten up my apartment. When I ignored her, she did the dirty work for me, dumping the booze and cleaning the untidy mess in which I was wallowing. I appreciated her attempts to help me, but her words and actions only plunged me deeper into despair.

Finally, in early August, she threatened to break off our relationship, confiding to me that she felt defeated. I persuaded her to give me one more chance. Beverly brought me to her apartment so she could look after me, and that night I killed off one last bottle of Scotch. The next morning, August 7, 1975, I checked in — ironically — to Beverly Manor, a civilian hospital in Orange County, where Dr. Flinn had made arrangements. The hospital had formerly been a nursing home, but was now well known as a premier alcoholism rehabilitation center. I stayed there for twenty-eight days under the care of the hospital’s medical director, Dr. Max Schneider.

Reprinted from the book “Magnificent Desolation” by Buzz Aldrin and Ken Abraham. Copyright © 2009 by Buzz Aldrin and Ken Abraham. Published by Harmony Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

falsefalseMore on Buzz